It makes sense that a gore-soaked horror franchise built around the universal fear that our time is running out would be as elegant and precise as a stopwatch. You can practically hear the ticking sound in “Final Destination Bloodlines,” the first new entry in the series in ten years. It’s a tour-de-force of voluptuously bloody slapstick that knows that we know how these movies work. It leans into that familiarity by staging a series of fiendishly elaborate deathtraps and giving us lots of time to admire their construction, note all of the rude, heartless, or complacent people who are fated to die super-nasty deaths, and keep a running list of all of the outwardly ordinary objects that are about to become links in a chain of destruction.

Are these movies deep? Yeah, in their way. Because they get you thinking about metaphysics, free will, and karma by killing people in chain reaction Destruct-O-Ramas that are framed, lit and edited with all the dark magic at cinema’s disposal.

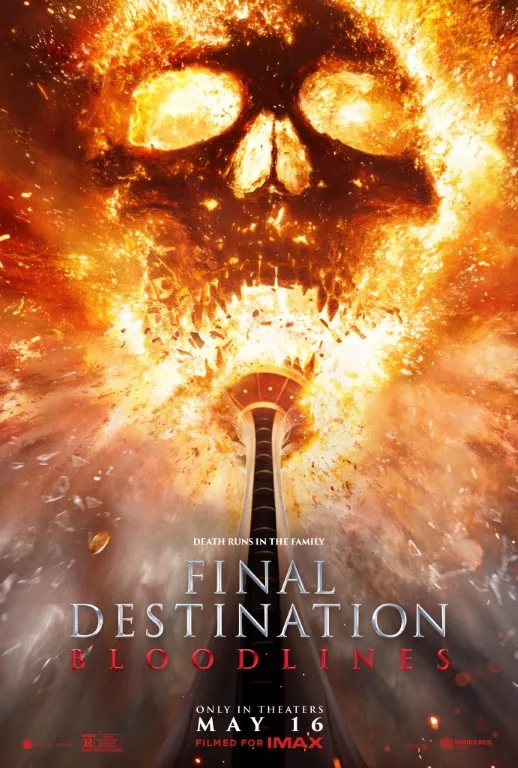

Co-directed by Zach Lipovsky and Adam B. Stein, “Bloodlines” is, per the subtitle, built around multiple generations in an extended family. Their genetic founder went on a date with her boyfriend in 1959, which was supposed to set the stage for a marriage proposal, but became a catastrophe instead. The location is a newly opened tower that resembles Seattle’s Space Needle. We know from our first glance at that thing that it’s going down, and it’s just a question of when and how. Soon enough, we also learn that Iris isn’t feeling queasy because she’s afraid of heights.

As Iris (Brec Bassinger) and her sweetheart Paul (Max Lloyd-Jones) board an unnervingly rickety elevator and make their way to the restaurant at the top of the tower, the filmmakers cut to so many closeups of incidents and objects that might come into play that you may laugh at how each new hint about where the scene is headed gets not just presented but unveiled, with distorted closeups and disorienting sound effects.

Remember “Chekhov’s Gun,” the writing rule that any element that receives a significant introduction in a story should be used somehow? This movie has Chekhov’s Beer Bottle, Chekhov’s Soul Band, Chekhov’s Nose Ring, Chekhov’s Garden Hose and Metal Rake and Trampoline, Chekhov’s Ice Water and Ice Bucket and Glass Shards, Chekhov’s Logging Truck, Chekhov’s Sputtering Halogen Light, and Chekhov’s MRI Chamber. This list barely digs beyond the uppermost level of Chekhov’s 2025 Murder Object Bag. When it comes to gifts that you did not expect, Death makes Santa Claus look stingy.

Iris, like many a “Final Destination” protagonist, has a detailed premonition of the catastrophe that’s about to unfold, but is killed anyway. But quite naturally, as per tradition, the splendidly elaborate account of her fate is revealed as a nightmare, dreamt by her granddaughter Stefani (Kaitlyn Santa Juan), who can’t get through the night without reimagining the tower collapse.

Wait, what? Granddaughter? Might that suggest that Grandma miraculously survived the disaster? And might she still be alive and able to deliver spooky exposition? And might the existence of a related extended family—including Stefani’s kid brother Charlie (Teo Briones) and her cousins Julia (Anna Lore), Bobby (Owen Patrick Joyner) and Erik (Richard Harmon), and her uncle Howard (Alex Zahara) and Aunt Brenda (April Telek), who warn Stefani and Charlie not to get obsessed with their long-disappeared mother Darlene (Rya Khilstedt)—set the stage for a return? Well, of course—otherwise, why would I have put an actress’ name between parentheses?

It would be unsporting to discuss the plot in more detail, because it might give away too many of the contraptions and a couple of plot twists that are as amusing as they are clever. Let’s just say that the collapse of the tower left ten to twelve names for Death to cross off his list; also, that there’s a reason why Erik owns a tattoo parlor, and it isn’t because we’re gonna get a tutorial on how to ink a tramp stamp; and that the filmmakers don’t keep referencing trains because they’re setting up a scene where everybody has a wonderful afternoon at the railroad museum.

These films are essentially anthologies of fated tragedies interspersed with discussions of free will and chance. They’re strung together by the idea that if you’re marked for extermination by Death but somehow end up getting spared, it will pursue you and everyone directly connected to you, no matter how long it takes to wipe you all out. Imagine an accountant traveling all over the world to correct a company’s faulty books. Or Ingmar Bergman’s “The Seventh Seal,” but replace the Grim Reaper with the people who design those domino-toppling displays that have a zillion moving parts.

There’s a lot of craft and wit on display here, all in service of an aesthetic not too different from the one that was ascribed to director Sam Raimi back when he was making films like “Darkman” and “Evil Dead” movies: what would it look like if the Three Stooges really poked each other’s eyes out? Like, if Moe jammed his fingers knuckle-deep into Larry’s eyesockets, then Curly came over with a chainsaw to finish him? This movie isn’t afraid to go too far, and I mean waaaay too far, from the very start, and keep pushing the outer edge of the envelope, giggling the entire time.

It also has a knack for what my dear Judith calls “visual colloquialisms,” transforming common sayings into pictorial statements or sight gags. Like the penny that figures in the opening flashback and keeps, uh, well, turning up like a bad penny. And let’s not forget that pennies are what you place on the eyes of the dead before loading them onto the ferry to cross the river and enter the underworld, because these filmmakers sure didn’t. Also, consider that when you toss a penny from a very high place, it creates a false impression of a penny from heaven, right before it makes an impression in your skull. Remember when older relatives would offer you a penny for your thoughts? Those are Stefani’s nightmares.

There’s a moment where a bystander enacts the ancient suggestion “See a penny/Pick it up/All day long/Have good luck,” and visualizations of “what goes up must come down” and “on the wrong track.” And there are needle-drops so knowingly corny that they become shared jokes between the movie and its viewers, like Etta James’ “Something’s Got a Hold On Me,” Air Supply’s “Without You” (with its desperate refrain “I can’t liiiiiiive…”) and Kelli Clarkson’s “Stronger (What Doesn’t Kill You).” I don’t know if they wanted me to think about the Christopher Reeve movie “Somewhere in Time” as well, but I did. See it if you can; it’s romantic and touching, and there’s a penny in it.

I digress. There’s a sober and thoughtful subtext in “Bloodlines.” It is similar to, but perhaps subtler than, all of the head games that are constantly being played in science fiction and fantasy movies about parallel timelines and universes, with their babble about “anchor beings” and “canon events,” and their discussions of whether you can really change the future or if your actions end up depositing your where the cosmos always knew you would go, by way of a different, somewhat longer route. There’s an argument to be made that it would save a lot of time if the folks marked for belated deletion by Death gave up and got it over with. But then the movies would all be 25 minutes long, and no fun.

Speaking of the grave: the late, great Tony Todd, who played funeral home proprietor, lore explicator, and series mascot William Bludworth, makes his final film appearance here, six months after his death from cancer. The result is not just a worthy sendoff for the character and the man who played him, but one of the very best scenes ever performed by an actor who knew he was dying and decided to make his last performance one for the ages. Hearing that rumbling voice come out of an emaciated and clearly suffering body is more unsettling than any of the film’s bloodbaths, but it’s also inspiring and moving. Todd was a consummate professional who wanted to give us one last thrill before he left, and he did.

But his cameo here is far more than a final IMDb credit. What he does here, in collaboration with his scene partners and the crew, is profound. He uses the inevitability of his death as fuel for his art, and retroactively deepens the whole franchise by connecting the reality of death to its spectacular representations onscreen. Todd knew when he showed up on set that he didn’t have much time left, and he knew that we would know that he didn’t have much time left as soon as we got a look at him. But he embraced all of that. What astonishing control and confidence the man had! Even in a weakened state, he knew he was still a badass with the presence, power, and voice to fill us with awe. I bet Death asked for his autograph.