Ryan Coogler’s thrilling and moving “Black Panther” is a rare superhero fantasy that’s plugged into the real world, even as it mirrors it in an inconsistent and distorting way. It’s sure to inspire scrutiny as deep as that which greeted the TV version of “Roots” four-plus decades ago, and that swirled about “Get Out” this time last year. Because it’s the most expensive film ever made with a predominantly black cast, and already the most financially successful, it’s being picked apart by detractors, because both its relationship to actual history and its apparent political messages are a morass of self-canceling idealism, only comprehensible in relation to the characters’ issues.

In that sense, it’s consistent with the rest of the big-screen Marvel Comics Universe movies. This franchise often plays around with explosive sociopolitical ideas only to put the pin back in the grenade at the end, lest one of the world’s most profitable properties be shaken beyond repair. In addition to all the other things “Black Panther” is, it’s an object lesson in what cinema is good and bad at. To say that “Black Panther” is as imprecise an analogy for oppression and revolution as “Star Wars” and “Star Trek” isn’t a slam against this film, or any Marvel film; it’s an acknowledgment that genre movies tend to work best when they’re anchored to emotions and big personalities, and run into trouble when the filmmakers or the audience try to map a geometrically precise relationship to the world beyond the screen.

These sorts of projects tend to showcase a lot of competing ideas that find a way to coexist when you’re watching the film, only to turn into a heap of broken images the second the lights come up. They all stimulate the imagination, though. And it’s a testament to Coogler and his collaborators that “Black Panther” has inspired more compelling and heated analysis in its first weekend than the rest of the MCU films put together have managed to do in the ten years since the release of the first “Iron Man.” “In the theater watching the credits roll on ‘Black Panther’ and someone just called someone else a colonizer,” Tweeted actor Dolores Quintana. “Excellent.”

Based on Stan Lee and Jack Kirby’s character, who was first introduced as a guest player in a 1966 issue of “The Fantastic Four,” “Black Panther” takes place in a super-high-tech African nation that’s like a cross between Shangri-La, Atlantis and Oz (the latter is playfully referenced in a throwaway line of dialogue stating that this place is not Kansas). With its mix of spears, shields, armored rhinos, latticework skyscrapers, magnetically powered monorail systems and insectile hovercraft, Wakanda is a dreamscape that splits the difference between an ancient, imagined past and a hopeful future. Its conception has less to do with Africa, the actual place, than with the rest of the world’s (and America’s especially) fantasies of Africa, as an abstracted cultural-political-biological motherland—a beacon that continues to inspire black folks around the world, despite the legacies of the slave trade and colonialism that Wakanda managed to avoid.

But this beacon is a troubled one. Wakanda is a sophisticated and rich nation posing as a chaotic “Third World” backwater. It managed to avoid the devastation that afflicted many of its African neighbors by keeping to itself and pretending to be poorer and less formidable than it was. Its miraculous technology — built around its exclusive supplies of vibranium, a substance that absorbs kinetic energy, and that was used in Captain America’s shield — could liberate the presently and formerly colonized nations of the planet, if only the king of Wakanda would share it. The last one didn’t. We can’t get a handle on this new one yet, and I admire how the rest of the film keeps introducing more doubts even as we grow to like and admire T’Challa (Chadwick Boseman), a fundamentally decent person in the vein of Wonder Woman, Captain America, the Christopher Reeve version of Superman, and almost every character played in the ’50s and ’60s by Sidney Poitier — American cinema’s original black superhero, even though the only super suits he wore were bespoke.

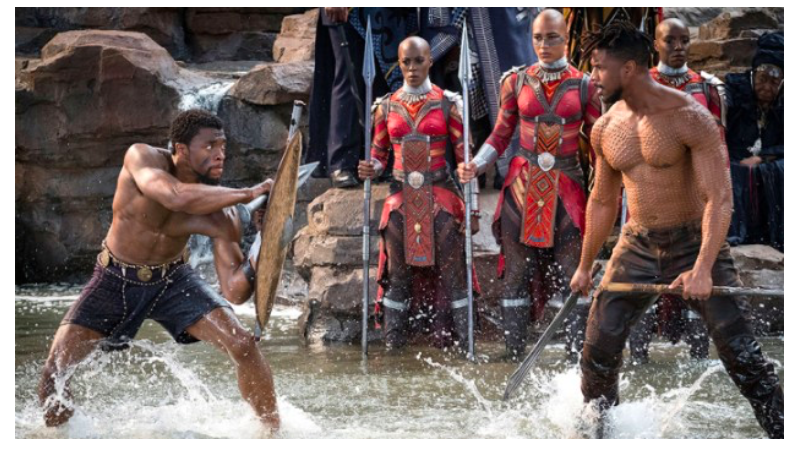

T’Challa ascends to the throne of Wakanda not long after the murder of his father, T’Chaka, in a bomb blast at the United Nations (an event depicted in “Captain America: Civil War,” and flashbacked here). He’s a dutiful son carrying a great burden. He seems mainly concerned with Wakanda’s status-quo survival, and with living up to the heroic image of his dad. He secures the throne in trial-by-combat at a mythic waterfall, defeating M’Baku (Winston Duke), the chief of the Jabaris, the only tribe in the kingdom that shunned the use of vibranium. Early on, T’Challa seems to be doing everything right. And maybe he is, in his own mind.

But not everyone agrees. The American Erik “Killmonger” Stevens (Michael B. Jordan), son of T’Chaka’s secret agent brother N’Jobu (Sterling K. Brown) and a prolifically lethal Special Forces veteran, wants to take over the throne, to avenge his father’s death at T’Chaka’s hands, but also to give oppressed people (including African-Americans in the United States) the high tech weapons needed to rise up. T’Challa’s best friend W’Kabi (Daniel Kaluuya), head of security for the Border Tribe, is disappointed to learn that T’Challa plans to continue his father’s isolationist strategy, and ultimately pledges loyalty to Erik. It’s clear from the civil war that erupts at the end of the film that Wakandans are divided as to how to interact with the rest of the world, and on the issue of whether isolationism and/or neutrality in the face of colonial oppression equals complicity-by-silence. Erik just brought their disagreements into the open.

The Wakandans are also hemmed in by their loyalty to tradition, which prevents people suspicious of Erik from resisting him when he defeats T’Challa at the waterfall and assumes the throne. (Interesting how it’s only a technicality — the challenge was never “complete” — that allows some of T’Challa’s most loyal allies to fight against Erik at the end; if T’Challa had submitted at the waterfall, Erik might’ve stayed on the throne.) The three-way fight between Erik, his spear-slinging badass of a general Okoye (Danai Guirira), and his science-wizard sister Shuri (Letitia Wright), who zaps Erik’s panther suit with energy bolts, is as much of a shadowplay of ideas as the slugfest pitting Tony Stark against Cap and Bucky at the end of “Captain America: Civil War.” But it’s a lot more powerful, because here the characters’ competing personal agendas are intertwined with the fate of a clearly defined setting, Wakanda, that means something to us emotionally—in Stark contrast to “Civil War,” where Buck and Cap’s bond is rock solid but the wider threats facing the Avengers are more vaguely defined.

T’Challa’s mission to South Korea to prevent the sale of an antique vibranium weapon shows that he’s engaged in a tricky political balancing act, and that Wakanda has understandable (if not necessarily likable) reasons for acting as it does. T’Challa pretends to be a credulous friend of the United States even as he electronically eavesdrops on CIA agent Ross (Martin Freeman) interrogating the mercenary Klaue (Andy Serkis), who led the robbery. Ross is referred to in passing, without affection, as “the colonizer.” We learn (through a narrated, intricately animated expository sequence) that Wakanda endured only because it sat out every major tragic-historical milestone of the past few centuries, including the slave trade and both World Wars. And we find out that Wakanda has spies in countries all over the globe, including the United States, site of the original sin that radicalized Erik: his father’s murder at the hands of T’Chaka. (Both this movie and the recent “Thor: Ragnarok” are about royal heirs unearthing the cover-ups of crimes by fathers who are also national father figures.)

Erik’s world view is so impassioned that he seems less a straight-up bad guy than a doppelgänger for T’Challa and the alternate leading man in “Black Panther.” He often speaks truths that sting, and that cannot simply be waved away by T’Challa and his supporters. He’s one of the most memorable antagonists in a big-budget genre film, right up there with Neil McCauley in “Heat,” Magua in “The Last of the Mohicans,” both screen versions of General Zod (in “Man of Steel” and “Superman II“), Bane in “The Dark Knight Rises,” and the Russian terrorist Ivan Korshunov in “Air Force One,” who tells the First Lady, “You, who murdered a 100,000 Iraqis to save a nickel on a gallon of gas, are going to lecture me about the rules of war?” “The world’s going to start over,” Erik promises. “And this time, we’re on top.”

The film has been widely celebrated, not just as a great superhero film but as a leap forward in representation, and it has been mostly embraced throughout Africa, with well-attended premieres in at least six countries. Eric Francisco of Inverse praises the look of the film as an “amalgamation of real African nations, economies and cultures, including Nigeria, Kenya, Uganda, South Africa and the Congo.” “The Afro-punk and Afrofuturism aesthetics, the unapologetic black swagger, the miniscule appearances from non-black characters – it’s an important resetting of a standard of what’s possible around creating a mythology for a black superhero,” Tre Johnson writes for Rolling Stone.

But Erik is so strong that he nearly unbalances the movie, in a way that no other Marvel screen villain has done. It’s his ideological conflict with T’Challa that makes politically minded viewers choose sides and root for one character over the other, even as they acknowledge that both men make valid points and are motivated by feelings that anyone can relate to. Erik is the abandoned/orphaned child, seeking to claim a version of that which was taken from him long ago. The character is more brutal and nihilistic than T’Challa. He’ll kill anyone who stands in his way, no matter how likable they are. His mentality is “if you’re not with me, you’re against me.” Other people are useful to him, but only as tools or resources. He treats women badly. He has no friends. These might be byproducts of his childhood trauma.

T’Challa is a better man, but no less troubled. He discovers that his father is morally compromised, then tries to balance his disappointment against his obligation to defend and perpetuate the kingdom that his dad once ruled. “It’s hard for a good man to be a king,” T’Chaka’s ghost tells him, an excuse of his own failures but also an undeniably true statement. Both T’Challa and Erik are grieving for lost fathers, and have spent their entire lives preparing to take the same throne. The mirroring here is reminiscent of the relationship between the main plot and subplots in certain Shakespeare tragedies, where we see two characters enacting versions of the same journey in the same play and ultimately ending up at odds with each other—like Hamlet and Laertes in “Hamlet.”

But some dissenting voices have argued that any film set in Africa, however fantastic, shouldn’t have a CIA agent as a sympathetic character and entrust him (and by extension, the United States government) with the country’s science fiction-level technology, given the agency’s historical role in overthrowing governments and helping colonial rulers. There have also been complaints that when T’Challa ultimately kills Erik and restores order to the kingdom, he’s destroying the film’s only true revolutionary for being a threat to Wakanda’s isolationist status quo—a twist that makes the film seem as backwards politically as it is fresh in its choice of characters and visuals. (T’Challa offers to use Wakandan technology to save Erik’s life, but he declines, and goes out with one of the most memorable exit lines of any recent bad guy: “Bury me in the ocean with my ancestors who jumped from the ships because they knew that death was better than bondage.”)

In a Shadow and Act piece titled “In Defense of Erik Killmonger,” novelist Brooke Obie quotes Nigerian writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s observation that the word Black “isn’t a concept in Africa,” and for various reasons “doesn’t make a ton of sense” there as it does elsewhere. Nevertheless, “…in an anti-Black world, a global identity and unity is necessary for the survival of the whole,” and Wakanda conspicuously fails to recognize that fact, which makes them seem arrogant and indifferent to the global suffering of people who identify as Black. He also writes “We are a homeless people, not welcomed anywhere. If Wakanda is the Black Promised Land, then we are its forgotten children, sold away, left behind, rejected, condescended to.” “The rage that Killmonger has against Wakanda’s passive role is so familiar because it’s the rage you grow up with when you’re black in America, being told that Africa is nothing,” Princess Weeks writes for The Mary Sue. “Everything about Killmonger is a commentary on what that mentality can do to the African-American mind. Even him choosing the gold chain to wear as his costume ties back to a ‘reclaim gold/diamonds from Africa’ mentality you hear in rap songs a lot, like the opening monologue of Jay-Z’s ‘FuckWithMeYouKnowIGotIt.'”

But if Erik’s feelings are relatable, they express themselves in a frightening, at times traditionally villainous way, which prevents some viewers from latching onto him as an antihero who makes more sense than T’Challa. This POV is articulated by Jason Johnson of Very Smart Brothas, who writes: “Killmonger’s desire to free black people from oppression was noble, but his methods were ridiculous and his motives were questionable. Wakandans didn’t resist Killmonger because of his ideas, [but because] they didn’t agree with his methods, which were, again, ridiculous. Black revolution in America hasn’t failed because we don’t have enough guns, it failed because white folks outnumber us 10 to 1, and that’s in some major metropolitan areas. Weapons for self-defense or chasing the cops and the Klan out of your neighborhood are one thing, but going to war against the United States would mean the extermination of black people no matter how many Vibranium-shielded rhinos you shipped to Ferguson. Now if Killmonger had wanted to turn Wakanda into a refuge for oppressed blacks across the globe, or bankrupt the imperialist powers in Europe and America by creating a single African currency based on Vibranium I’m pretty sure T’Challa would have at least been willing to check out a Powerpoint.”

Another big problem with Erik’s plan, apart from what it would do to Wakanda, is that it replicates the mentality of imperial powers like the United States, which trained him to kill and let him practice his skill against people of color in Afghanistan and Iraq. Erik clearly states that he doesn’t just want Wakanda to help the world, but to rule it. This is a classic example of the representative of an abused minority replicating the values of an oppressor without consciously realizing he’s doing it.

As for T’Challa, it’s unthinkable that he could ever embrace Erik’s plan anyway for extra-dramatic reasons: it’s just not the sort of thing that could happen in a Marvel film that costs over $200 million and needed to appeal to a wide swath of viewers to be profitable, including some white viewers who might be skittish about attending a film called “Black Panther” no matter what. The end of the movie triangulates a new position somewhere between Wakanda’s political stasis and Erik’s burn-it-all-down fervor: Erik’s T’Challa incorporates a version of Erik’s viewpoint, establishing Wakandan outreach centers and going before the United Nations to reveal his country’s true nature to the rest of the world.

There’s no indication that he ever seriously considered handing Wakandan weapons to oppressed people, as Erik would have done. But this only means that T’Challa is truly a mainstream superhero despite the color of his skin. Preservation of the status quo has been the modus operandi of white heroes throughout pop culture history, including Superman, Batman, Buck Rogers and the Lone Ranger: express sympathy for other people’s pain and do what you can to alleviate it, but not if it means tearing down the structures that raised you (whatever their flaws) and that claim you as a favorite, exceptional son. Thus the Lone Ranger will battle crooked land barons who run poor settlers off their homesteads, but he’s never going to go the extra mile and reclaim the land for Tonto and his people. Superman might chastise a racist or even beat up Nazis or Klansmen, but he’ll never take the United States government and military to task for institutionalized racism or homophobia. And T’Challa isn’t about to start a war with the world’s superpowers by arming the people they oppress.

There’s a sense in which Wakanda owes as much to the United States’ self-image as it does to dreams of African supremacy. A key part of this country’s patriotic myth is the notion that, until World Wars I and II, it was shut off from the rest of the globe, and only engaged with its troubles reluctantly. This is nonsense, of course: the United States was always involved in other countries’ business, and had been the object of, and instigator of, many wars prior to the 20th century. But the myth still resonates, and there are shards of it embedded in “Black Panther,” a lead-up to “Infinity War” that finds a once-isolated superpower, Wakanda, being pushed into a wider (intergalactic) conflict to save the world it once hid from.

To imagine this scenario is to envision an “African America”—a loose confederation of territories/tribes united by basic shared values. T’Challa is willing to let Wakanda engage with the wider world, but only on the country’s own terms, which are more limited and self-preserving than anything Erik might have envisioned. He’ll modify Wakanda in hopes of modifying the world, but he won’t destroy or dismantle it. He’s a politician, not a revolutionary.

Of course, the fact that it’s the outsider Erik, not the insider T’Challa, who expresses imperial ambitions for Wakanda is yet another bit of evidence that films like “Black Panther” tend to turn to mush as soon as you start examining their analogies and symbols. Fiction films aren’t built for this kind of rhetorical argument. If you try to draw lines connecting every part of them to something out in the real world, things are bound to get tangled up and become frustrating. Both the characters and the people who brought them to life are complicated and contradictory. They don’t make sense even when they do, and they make sense even when they don’t. If you ask fiction to do the work of rhetoric, you’re bound to be disappointed.

Meanwhile, the marketplace imposes its own limitations. Erik’s demise confirms that no matter how superficially innovative a Marvel film might be—in terms of its story and characters, and even some of its themes—it is ultimately just one piece in a global moneymaking enterprise comprised of mostly white characters, and therefore can’t rock the boat too hard. That the “Black Panther” characters will make their next appearance in “Avengers: Infinity War”—the biggest ensemble adventure in Marvel film history—gives some indication of what Marvel considers the Wakandans’ “place” to be. They’re ultimately no more important to this fictional world than Iron Man, Thor or Captain America. Coogler’s movie builds such a distinctive self-contained universe that it’s a shame to think of the characters being reduced to fringe players in a Marvel yearbook-photo-in-motion, delivering between 10 and 40 expository lines each when they aren’t punching people in the face.

Whether you see T’Challa’s story as a disappointing confirmation of this franchise’s limitations or a refreshing indication of how flexible it can be will depend on what you expect from superhero movies as a genre, and from profit-driven American popular culture generally. Films like “Black Panther” are great at tapping into powerful but amorphous feelings—like the resentment that some descendants of the African diaspora still feel towards tribes (and nations) that sold their ancestors into bondage, and the sense of wonder that accrues when you imagine an African nation that was allowed to develop “off the grid,” without significant interruption by war, the slave trade or colonialism. But they’re pretty awful at articulating actual political arguments, or any kind of argument that’s not rooted in emotion. Films, like dreams, are great for sparking questions, but they tend to be nonsensical objects in and of themselves. That’s why people get puzzled or bored when you describe them. They only make sense when they’re playing on the movie screen of your mind.