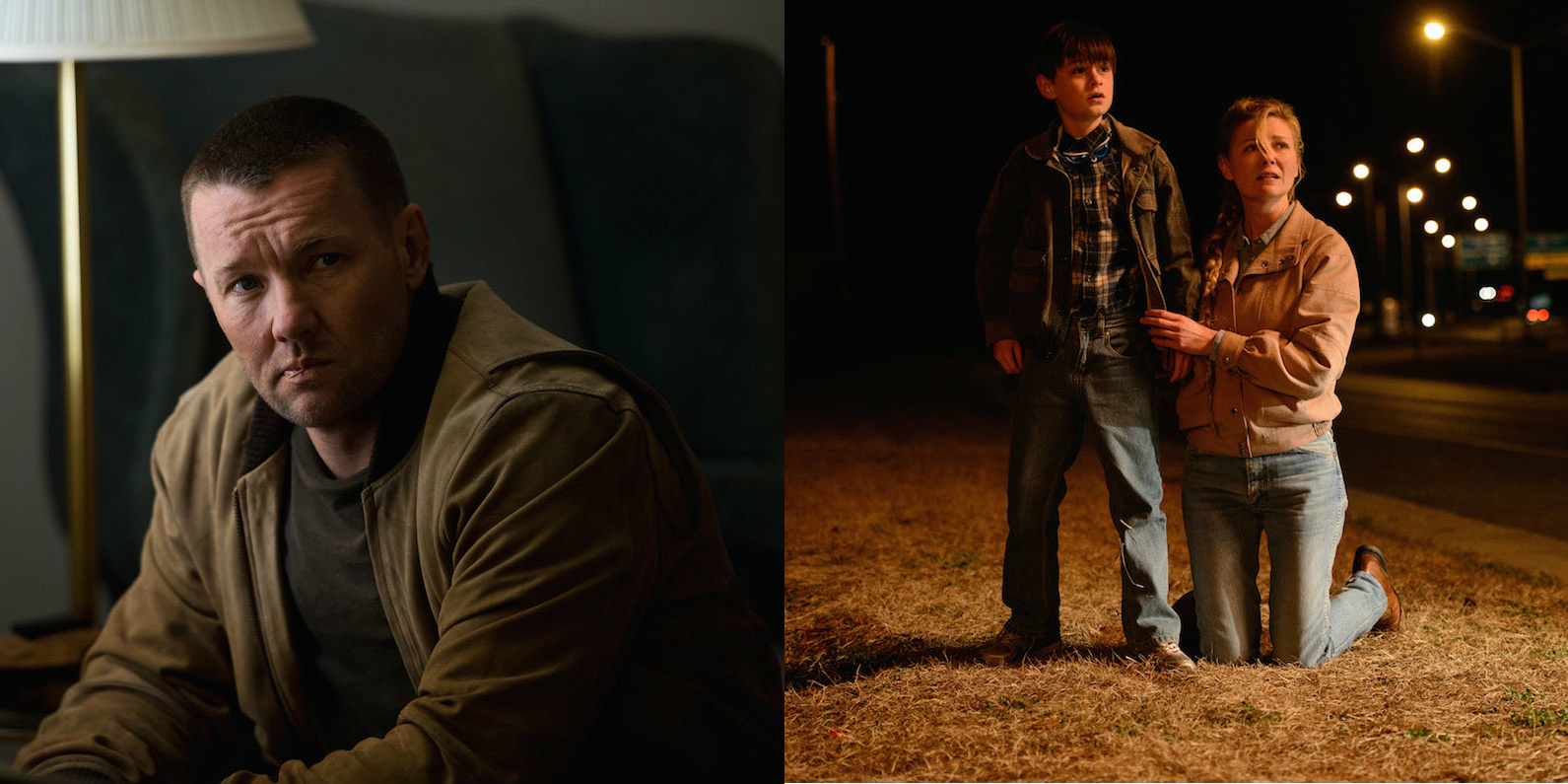

Writer/director Jeff Nichols’ fourth film, “Midnight Special,” is a sci-fi thriller not quite like anything you’ve seen before. Starring Joel Edgerton, Kirsten Dunst, Michael Shannon, and Jaeden Lieberher, the movie premiered at the Berlin Film Festival last month and opens stateside on March 18. In it, Shannon plays Roy, a father on the run with his son Alton (Lieberher), who has developed mysterious powers that make him an object of interest to both a religious cult and the federal government. Dunst plays Sarah, the boy’s mother, while Edgerton is Roy’s childhood best friend, Lucas, who now travels with the family as a sort of bodyguard.

Edgerton and Dunst spoke with RogerEbert.com in Berlin after the film’s premiere about their roles, working with Nichols, and what you learn about belief and meaning from working on a film like “Midnight Special.” (You can read our interview with Nichols and Shannon here.)

You haven’t worked with Jeff [Nichols] before, right?

JOEL EDGERTON: I have since worked with him again [on “Loving,” in which Edgerton plays the lead opposite Ruth Negga], but this was my first time.

How was it? He seems like a director where the stories come fully formed to you as an actor.

Yeah. There’s detail in a full, rich tapestry there. And it goes beyond the frame. Jeff can answer any question about the world of his movies and his characters, because there’s been so much careful consideration put into it ahead of time. I don’t think, from memory, I’ve ever worked with someone who’s laid out such a clear vision for what the finished product ends up being. If you laid his ahead-of-time vision against the finished product, they’re kind of doppelgängers of each other.

Huh. So how does that affect your process as your preparing for the role?

Well, sometimes—and only sometimes—you hit certain key moments where you realize Jeff has such a clear idea of what it needs to be. At first I would always struggle against it because I felt like there needed to be a real fluidity. Then the last time I worked with him, I just sort of went up to him one day (we were running out of light) and I said look, just tell me as clear as possible the way you see this moment. And he would go, “Okay.” And then it’s like—it’s like Jeff’s the master, and I’m the dog, and he throws the stick, and I’ve gotta go fetch it for him. There’s a certain pride in that. There’s a certain rigidity to his vision, and yet there’s a fluidity to the role of the actor within that. You just gotta know what the parameters are. You gotta know what the parameters of his vision are.

And sometimes—actually, quite often—you could educate him, in the nicest possible way, that there was another way ’round. As an option. And quite often, he would say, “I hadn’t seen it that way, but I like it better.” I often think that having boundaries or fences or parameters creates a greater sense of freedom, because you know what your limitations are, and then once you’re inside those parameters, you can have an abundance of freedom and detail. Whereas if a director or a scriptwriter is too loose in their vision, then I waste my time trying to decide where to place myself.

So with this character, then—who’s a really interesting character, partly just because he’s so quiet, and solid—

Yeah, he’s like a big, quiet, simple, strong bodyguard. What I love about the place Lucas holds in the story is that he’s not the father of the child. He doesn’t have to be there. He makes a choice based on catching this glimpse in Alton, of purpose, perhaps, beyond the day-to-day, nuts-and-bolts, practical life he has been living. And he’s willing to just uproot himself, leave his old life behind, and risk everything to move forward, hoping to gain confirmation of something brighter and more interesting.

He’s the only character in the film who’s never been part of the Ranch. Did you feel like he saw the situation differently because of that?

I like to think of Lucas as in—I have a particular opinion, a fear, a weird kind of distant opinion about cult behavior, about cult life, and a judgement of people who participate in it. Deep down, I think there’s a certain weakness to that behavior, and I like to think that Lucas saw Roy in that way: We used to be friends, and you drank the Kool-Aid and went a bit weird. And then [Roy] pops back in. I think Lucas is a practical man without faith, who then becomes, overnight, devoted to something different, and is still questioning it. He still questions whether to take Alton to a hospital or not. He’s not blindly following this thing one-hundred-percent. But I think he’s devoted to the mission to find out what’s next. And that’s why I find it interesting. He’s like this very simple bodyguard, who’s there to do whatever it takes to just be there, and be along for the ride.

When Roy called him up, how does Lucas respond to that moment? It doesn’t happen on screen.

I think there’s something to be said that’s very cunning and shrewd about Roy—of all people, I don’t think he went door-knocking and Lucas was tenth on the list. I think he went straight to Lucas, knowing that he was a police officer, knowing that he had weapons, knowing that he was a physical and capable enough guy, and knowing that he was an empty vessel that could be filled by the rapture of this special boy. I think that was a cunning move on his behalf. I don’t think that Lucas had as full a family life—you never know what he might have left behind, but there’s also a sense of loss and melancholy about him. He has left something behind. And he has literally turned his back on something. Whether that’s a family or whether that’s just a career, everybody’s connected in some way, and no one’s an island. I think Lucas has definitely sacrificed a lot.

Did Jeff know what Lucas had left behind?

We discussed it. There was room for movement there. But definitely Jeff has an opinion about everything. That’s the great job of a director: they need to have an answer for everything, even if you make it up on the spot. But Jeff’s not a make-it-up-on-the-spot kind of guy. You know he’s thought about it. It’s like he’s looked at everything in its dimensions. He’s not just standing there looking at a facade; he’s walked around it, he’s looked at all the sides and angles, and asked himself all the right questions.

I don’t remember who the director is now, but I know there is a director who would tell every actor something different about the situation, so they were all playing it differently. I’m not an actor, though, and I have no idea how that works.

I’ve often thought it would be good to write a screenplay and just refuse to give certain storylines to particular actors. I’d be interested in the experiment: if someone’s under interrogation and he’s denying any involvement in a crime, I’d be really curious to know what the experiment would be like to fool an actor into believing they are actually telling the truth, and then put it in the movie in the context of being guilty, and see how that could feel. As an actor, you want the power to choose the signals you’re giving. But I personally don’t mind if the director tricks me into something. I wouldn’t mind if the director used a moment and supplanted it somewhere else in the movie, if it made the movie seem better. I know certain actors would be offended by that; I personally wouldn’t be. I’ve done that as a director. I’ve taken a look from the end of a scene and put it at the beginning of a scene. And it works.

What did you find in this character that you were able to dig into? He’s a big Texas guy, solid and quiet.

I struggle with what’s out there in the sense of faith, and what am I devoted to. I sometimes literally wake up, or have trouble getting to sleep, because I suddenly am ruminating, like, What the fuck am I doing? Why am I doing what I do? It’s all work-related, what I hope for myself in terms of a fuller life. Is life just going to be a series of movies? Am I devoting my life to fiction? Those questions about purpose, and what is purpose—I think about that stuff a lot. And that was a way for me to kind of get into him.

That’s interesting, because at the end of the day, I was trying to think, What does Lucas believe he’s trying to do? Does he believe he’s trying to save the world? Or the kid?

I think what’s interesting is that Roy has brought Alton and presented him to Lucas in order to employ Lucas, and to bring Lucas along for the ride as a protector. And I think that Lucas is not one-hundred-percent devoted to the vision that he’s seen in Alton. It’s just that he’s been given a clue to something bigger, and he’s going to continue on that road, to be devoted to protecting that child, on the hope that he gets some kind of further answer or some kind of further vision, or some kind of seat at the table of something bigger.

I feel like that’s a theme in Jeff’s films: there are these people who have a sense of something happening over their heads, but they’re not sure what it is. They’re trying to be part of it.

Yeah. There’s a great quote—I don’t know it exactly, but Daniel Day-Lewis’s father [Cecil Day-Lewis] was a poet, and I remember this great concept. He had said something akin to, ”If man were to discover the meaning of life, the language he has given himself would make impossible for him to describe what he’s seen.” You ever have those moments where you catch a feeling, and you stumble to try and articulate what that meaning is? And you may only get so close to describing it. If you were to have to describe a vision or a feeling to somebody else, how do you do it? There’s something about the movie that is wonderful, that Jeff has kind of left an empty space on the canvas for the audience to fill in some of those gaps, to bring their own experience of faith, or devotion, or a longing for a greater purpose. What is that to you? You can go watch this movie and sort of inject a bit of yourself into it.

The end is so beautiful, but you’re not sure why. There’s that feeling of wonder.

I know there’s definite nostalgic elements that remind you of “Starman” or “Close Encounters of the Third Kind,” but there’s something about the end of the movie that’s reminiscent of “The Abyss.” Sure, there are alien movies where it all gets reduced to a gunfight, us versus the weird aliens, but I like a kind of open-minded essence of camaraderie. There’s a feeling at the end of “The Abyss” like there’s something bigger out there, and it needs to harmonize. We need to harmonize. And it says something about the way we need to harmonize with each other. There’s something about the ending of Jeff’s movie that reminds me of the feeling at the end of “The Abyss,” coming out of the ocean.

This was your first time working with Jeff.

KIRSTEN DUNST: I was a fan of Jeff’s before. I wouldn’t need to even read a script; I’d just say, “I’ll do whatever you like, Jeff. I love your movies, and want to be a part of them.” I want to have a relationship, too, with quality filmmakers that I really love and respect, and so I need to be in their movies.

But he made me audition for it!

He’s a writer/director, so it seems like the film comes pretty fully formed from his head.

Yes.

Which is interesting for your character, because I feel like there’s all this backstory that we have a general sense of, but no specifics. Did you have a sense of what Sarah’s journey had been to the point where we meet her?

Yes. What Jeff talked to me about was that maybe Sarah was into drugs, maybe, got disassociated from her family, and found the Ranch, got sober, met Roy there, they had this child. When his supernatural powers started to happen, they latched onto him, and the leader of the Ranch wanted to raise him as his own son. Sarah wouldn’t allow it, so she got excommunicated. So then we meet her two years later, and I think somewhere in those two years, [Roy and Sarah have] obviously communicated and set up this plan. But I think that Sarah’s definitely a person—I feel like I’ve met people like this before, who’ve had so much trauma in their life that they kind of live more in the moment, and they’re kind to everybody, and they have a more appreciative attitude; they’re very grateful and gracious. I feel like Sarah’s that kind of a woman. She also couldn’t call the cops, because her son has powers, and then she’d be a science experiment. So there’s a lot of conflicting things there, and I think that she is a very saintly woman, to be honest.

Did you feel like she’d been a true believer while she was there, at the Ranch?

I think she was. She kept her braid! It was like she hates the Ranch for what they did to her, but I feel like the Ranch also saved her. So the fact that she kept that modest thing—I know our ranch isn’t Mormon specifically, at all, but in researching I found this one girl online (it’s been a while now, over two years ago) [who spoke] so much softer, and there was this whole saying, keep sweet for your husband. So she has that in her. That’s just the vibe of the way that she’s been brainwashed.

Her relationship with her son is so interesting because she hasn’t seen him in years—and he’s a kid, but also not really a kid.

Yes. But I think—I don’t know, I haven’t had a kid yet, but if my kid spoke funny, or whatever it is, that’s your kid. You’re used to it. So I feel like as soon as she sees him again, she knows the routine, with the goggles. She’s a mom. It’s like, “I know what food you like.” So I feel like she just goes back to her motherly duties of protecting her kid.

As I was watching the big scene …

I was just looking in the clouds, and sweating so badly in that sweater and jeans and boots. I was like, “I’m dying,” looking at the sky and crying at nothing. [Laughs] It’s the most important part of the movie, and it’s the one part where I’m left to do it all on my own. That’s why Jeff hired me. That one scene.

And we’re watching your face like this [gestured to a close-up]—

I know! Believe me, I was watching it the other night, and I was like, I’m gonna close my eyes. That braid!

What is she going through at that moment?

I did so many takes with Jeff of that. In the beginning I was really breaking down—that’s my son who just left me forever. And Jeff didn’t want the audience to be sad. He wanted it to be like pull up your bootstraps, this was a greater cause and I’m going to be a stronger woman. I remember I would walk away into the woods. You would see me walk slowly. And he would be like, “No! Run back into the woods like you hear a helicopter coming!” And I was like, okay, I got it. It’s a more masculine way to play it, which is interesting. But my instincts as a woman—he didn’t do a take with one teardrop. He wanted the restraint. But that’s Jeff’s style. He likes the restraint.

I felt like you could read it as a mother losing her child to an illness.

Oh, that’s a really nice metaphor. I’m going to use that.

Losing a child, but feeling like he’s in a better place, and he’ll always be there.

Yes. But that’s a fast transition in one—that’s the thing. I was like, “Jeff. It happens in just a few beats. That’s a lot to cram in there.” That was not an easy scene. I was happy when that day was over.

One effect of that, though—obviously, it’s like sci-fi and also really realistic—is that it feels almost like a fable at that point, because it’s a surprising thing that she does.

Yes. I wish they’d make a sequel to this movie. I would be into it.

I would watch the TV show that’s just about Sarah.

I like your style.

Did you have a sense of what was happening at the end when she cuts her hair off?

I feel like it’s a classic thing, like—isn’t it “Terminator”? She cuts her hair, it’s another ode to a movie, she’s gonna die it black. Next Sarah.

It feels like a symbolic gesture, but it feels like something’s actually getting cut at that moment.

Yes. One woman today said, “I was so happy when that braid got cut off!” I was like, I love your concern about my looks! [Laughs] I think that was definitely the shedding, but also I thought of it like now I can be free of everything. Job well done. We did it. That was in additional shooting we did later, because people were like, “What happened to the mother?” That’s what happened to the mother.

What was it like working with Michael Shannon? He’s intense.

He is intense! But I can get along with a lot of different personalities, and I get along really well with Michael. But I think I would be nervous if he didn’t like me—he just says it like it is. I really enjoyed him. He respects me, and I respect him, and that’s really nice. But the best actors, directors—the most complicated characters I’ve worked with are usually the best at what they do. I’d rather work with people that are damn good. I don’t need to be everyone’s friend.

Do you feel like in playing this character, you discovered anything that surprised you? About the character or you?

It was a very boys’ set to be on. It was interesting. It’s funny to be the only girl. I mean Sarah [Green], our producer, thank God, is a woman too, so I talked to her a lot.

And Jeff makes very masculine films.

I think his biggest female role was probably Jessica Chastain [in “Take Shelter”], don’t you think?

Yes, that’s right.

I’m hoping he’ll change. I’m like, just write it for a guy, Jeff, and then just change the character to a girl.

He does go with stereotypically—well, “Take Shelter” is about anxiety, which is often done with a female character.

And family. But yes. I just want to work with good directors, that’s it … How old are you?

32.

Yeah, okay. I figured you were around that. All my friends who saw [“Midnight Special”] loved it. I feel like it’s a good our-generation movie.

It feels like it’s dealing with things below the surface we know about.

And I feel like it’s subject matter that I am really curious about, like weird religious cults. I watched all things about Warren Jeffs [the FLDS leader]—before I did this I was a sister-wife for Halloween with my girlfriend before I got this. So I’m really into this side of the religious spectrum.

Did you watch [Amy Berg’s] “Prophet's Prey”?

Yes. So good. They’re going to make that movie, “Under the Banner of Heaven.” All that stuff.

The calico dresses with the puffed sleeves.

Yes! Did you watch “Big Love”?

Not yet.

It’s a good one. I loved “Big Love.” Those dresses.

The puffed sleeves make me think of “Anne of Green Gables.”

They’re crazy!