Shula (Susan Chardy) is tired, driving home in a Missy Elliott costume she wore for a friend’s party, when she sees something strange on the road ahead. She slows down, reverses and realizes it’s the dead body of her Uncle Fred. She calls other family members to tell them of her discovery, starting a chain of events that will dredge up repressed memories and heartbreaking secrets hidden in her large family in Zambia. As the exhaustive preparations for her uncle’s funeral commences, Shula and her cousins grow closer as Shula realizes the pain this uncle caused the girls and women of the family for generations.

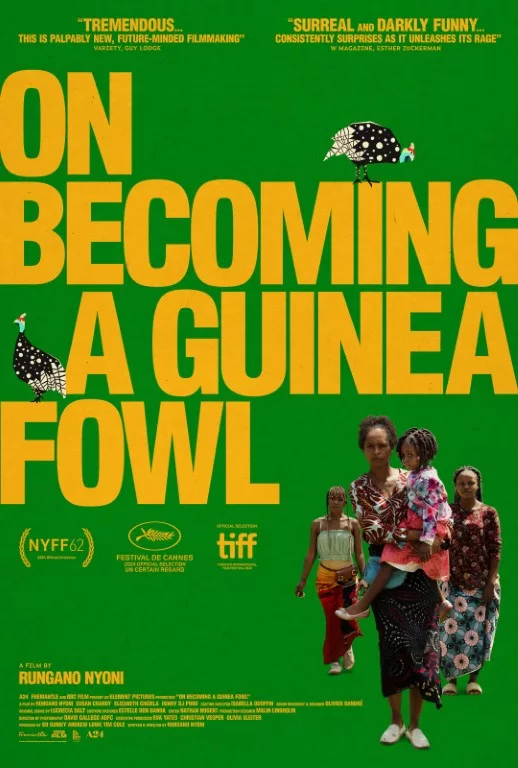

Rungano Nyoni’s “On Becoming a Guinea Fowl” is a surreal and emotional journey through one family’s pent-up trauma. The ensuing funeral is an intense affair, bringing dozens of relatives to cram together in one house and forcing the younger women to run errands and cater to the needs of the guests. At the same time, Shula goes through her own personal emotional rollercoaster, hiding her disdain–maybe even disgust–for her uncle before realizing how many girls in the family he hurt in the past and how he continued to hurt his young wife. Shula’s family, siding with the abuser, lashes out at the widow and blames her for his death, unleashing even more pain at this somber occasion. “On Becoming a Guinea Fowl” is a complex film about the silence and repression of survivors and the grief that remains even after the assailant is gone.

Nyoni, who burst on to the international film scene with her visually stunning debut “I Am Not a Witch,” continues to develop her unique style. In “On Becoming a Guinea Fowl,” she incorporates the significance of the title’s bird to explore the family’s story, explaining through flashbacks to a kid’s program that the guinea fowl helps keep the rest of the animals safe by warning them of potential predators. But this is just one creative use of nonlinear imagery to develop her story, as Shula’s dreams become stranger and stranger as her uncle’s death takes a toll on her. At various moments, visions of her younger self come into view or her younger self steps in for the grown-up Shula, representing how a given moment makes her feel. Nyoni channels other filmmakers like Luis Buñuel’s editing tricks that make a viewer (and Shula) question if what they’re seeing is real and Andrei Tarkovsky’s reflective use of water in “Nostalghia,” especially in a dream sequence where water seems to be flooding around her sleeping relatives but no one notices except Shula, who walks past in awe as the vision ripples and dances across the screen.

Likewise, Nyoni’s screenplay finds some moments of reprieve with a streak of absurdist humor and the developing relationship between Shula and her relatives. The tone becomes bittersweet as Shula bonds with her cousins, Nsansa (Elizabeth Chisela) and Bupe (Esther Singini), and realizes how much they have in common. The outgoing Nsansa fights her own demons and expresses her pain in a vastly different way than Shula, who takes on more of a poker-faced approach, hiding her emotions from her family. As Shula, Chardy doesn’t give her story away. Years of keeping secrets are reflected in her stiff face, steady shoulders, and detached stare. She will not cry for someone who doesn’t deserve it. She attempts to talk with her parents about Uncle Fred’s crimes but finds her mother is too grief-stricken to reckon with the pain of others and her father is too checked out, choosing instead to enjoy his life and not worry about others’ needs. Much of “On Becoming a Guinea Fowl” centers on the experiences of the women in the family, swapping gossip, making decisions, or worse, ignoring what they know of the situation. They either perpetuate the violence or put a stop to it, and the movie emphasizes that it’s a choice every one of them must make for themselves.

“On Becoming a Guinea Fowl” is an uncomfortable but entrancing watch, a tribute to shattering silence around family secrets and bucking tradition for the sake of empathy. Nyoni and cinematographer David Gallego conjure up dreams and drama with equal ease and effectiveness. Gallego, who previously shot breathtaking movies like “Embrace of the Serpent,” “Birds of Passage,” and “I am Not a Witch,” blurs the line between reality and perception to immerse the audience in Shula’s experience. If each woman in the movie is forced to make a decision with the knowledge they have, the audience must also decide for itself how “On Becoming a Guinea Fowl” will affect them the next time they see their family members in the wrong.