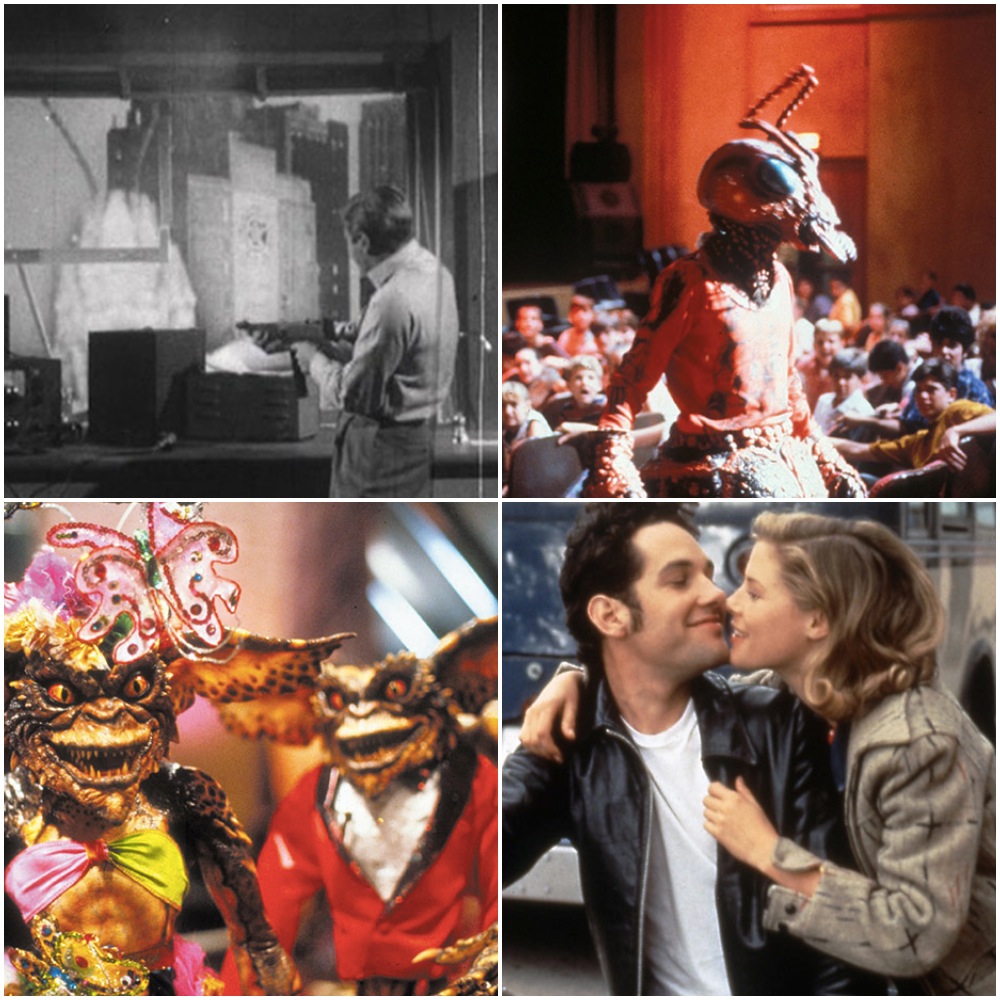

In some ways, “The Movie Orgy” is the key to understanding American filmmaker Joe Dante‘s omnivorous cinephilia. Dante (“Gremlins,” “The Howling“), now 69 years old, spliced together “The Movie Orgy,” a compilation of cartoons, advertisements and various movie footage. “The Movie Orgy” used to last seven hours long, but in its current form, runs about four-point-five to hours. Dante’s cinematic collage has no narrative, but plenty of thematic “points of contact,” to use a phrase film coined by critic J. Hoberman. It’s a hallucinatory blend of surreal violence, droll humor and madcap counter-culture ideology.

BAMcinématek hosted a free screening of “The Movie Orgy” this past Sunday during the first weekend of their ongoing “Joe Dante at the Movies” program, a series of films programmed by Dante that ranges from his films to off-beat Dante favorites/influences like Mario Bava‘s “Lisa and the Devil” and Norman Lear’s “Cold Turkey.” I spoke to Dante on Saturday about editing movies, selling toys and preserving films, shortly before Dante introduced a double feature of “Gremlins 2: The New Batch” and “Hellzapoppin.”

Of the movies you selected for BAM’s program, a couple titles stand out, like “The Fool Killer.”

Where’d you see “The Fool Killer?” That’s a hard movie to see. It played some dates in the South, where it was shot in 1963. In ’64, it played for a week. It didn’t go anywhere, so they took it off the market. And then it circulated on 16mm, which is how I saw it. I rented it for [home video company] Films Incorporated, and ran it at the Philadelphia College of Art. That was the Philadelphia premiere of the movie, in 1965. Then it opened in New York in a slightly different version for about two days, and then got pulled. I went up to Eli Landau, the producer of the picture. I saw him at some event. And I told him how much I liked “The Fool Killer.” And he rolled his eyes! “Ugh, ‘The Fool Killer!'” Which led me to believe that there was some difficulty making the picture. Which is a shame, because I think Servando González is a very talented director. This was his first English language movie—and nobody got to see it.

It’s great to see that film paired with “Confessions of an Opium Eater.” Programming really good double features is something of a lost art, though understandably so since they aren’t such a vital part of some movie theaters’ business model.

Very tragic. The demise of the double feature is one of the saddest aspects of my life in moviegoing. When I made “Piranha,” and it opened in L.A. on a single bill, I felt like I was cheating the audience. Because that was the kind of movie I used to always go to see on double bills. In the ’60s, everything was double-billed. There were movies that were made specifically to be second features. And sometimes they were better than the main feature. You always felt like you got your money’s worth. Now, having all the onus on one movie, it’s like a great burden to me.

Getting a print for some of the movies you’re showing—like “Mickey One”—isn’t easy. That one is showing on its own, outside of a double bill. What can you tell me about programming that one?

The studios have started to catch on to the fact that sometimes, there’s a market for theatrical and festival revivals for these older pictures. So, because of places like BAM, and the American Cinematheque in L.A., and some other places—the studios have been cajoled into making a new print. With “Mickey One,” Columbia decided to make a print about five, six years ago. I’m sure that’s the print they’re running.

The tragedy is the demise of 35mm projection. Scads of movies that used to be available are now unavailable because it’s so expensive to make a DCP. Studios are not going to spend money on making a DCP of a niche movie that’s only going to play four, five dates a year. So there are many movies that … I mean, there’s no DCP of “The Howling.” There’s a movie that’s frequently revived, but nobody’s spent the money to make a DCP. So they always wind up running my print. And my print is getting old. It’s an older print. It’s not an original print; I had it made later. But the wear-and-tear it’s getting—because it’s the only print available—is multiplied by hundreds of other movies. Thousands of other movies that don’t exist in any other form but a 35mm print.

It’s a very hard job to be a festival programmer because, well, where are you gonna get this stuff? The majority of the films I programmed was chosen because A) it had influenced me in some way and B) I knew it was available. There’s a lot of other movies I would have run. There’s no Sam Fuller, there’s no Sergio Leone movies. It’s a choice of what you can get to run. I was told there was no prints of “His Kind of Woman.” And they found a 16mm print. I have a 16mm print. The idea of running it in 16mm is not ideal. I’d actually rather run a DCP than a 16mm print, because there are limitations to the sound and picture. But you run what you can get. It’s tragic that it’s so difficult to find prints of movies that used to be fairly common.

The seeming random-ness of which films get DCPs and which don’t is baffling. I saw a gorgeous-looking DCP of [spaghetti western] “The Big Gundown.” And yet, there are some cinephiles that are so snooty because it’s a DCP. As if they’re holding out for a print.

That’s a mistake. “The Big Gundown” is a drive-in movie, so prints are tattered. They’re Technicolor prints, but they’re beat-up. When Quentin Tarantino bought the New Beverly theater, and switched it over from DCP projections to all 35mm, that meant that the prints had to be whatever prints were available for the movies that they run. And they’re very grindhouse-oriented, so many of them come from Quentin’s collection. Many of them vintage prints from the year the movies came out. They’ve played in grindhouses, they’ve played in drive-ins. Sometimes splices, sometimes faded … Quentin likes that. He likes that grindhouse experience.

You saw “Grindhouse“: the whole idea of the movie is that it had the scratches, and the splices and the seams. But the studio didn’t do anything to acquaint audiences to the fact that there used to be such a thing as double features. So when audiences went to that movie, they walked out after the first feature, not realizing that there were two movies! That’s why calling it “Grindhouse” made it sound like a horror picture about butchers, or something. It didn’t find its audience, and there is an audience for it. They just needed to be educated as to what they were watching. I don’t think the picture exists as a double feature, but rather as separate items.

You can get ’em on separate Blu-rays now. Switching gears for a moment: there’s precious little written about one of your movies that BAM is screening for this retrospective: “Runaway Daughters.”

That’s because it was part of a series I did for Showtime called Drive-In Classics. It was produced by Lou Arkoff, son of [American International Pictures producer] Sam Arkoff. They wanted to remake a series of old AIP juvenile delinquent movies from the ’50s.

Like “The Fast and the Furious.”

Yeah. So they eventually called it “Rebel Highway.” They did 10-12 episodes directed by William Friedkin, John McNaughton, Ralph Bakshi, Jonathan Kaplan. They did these very low-budget remakes … most of them weren’t really remakes. In fact, mine was the only real remake. The reason why I chose it is because it had a lot of adults in it, and I wanted to use all my friends as parents and stuff. Charlie Haas, who wrote “Gremlins 2,” wrote it. And we made it in 10 days. That was the dictum, you had to make it 10 days. Until one director needed 12 days, so everybody got 12 days after her. I said “Wait a minute, why didn’t I go after her?” [laughs] It was very well-received. It’s a very funny movie, a riff on ’50s movies, and Douglas Sirk, lots of other kinds of stuff.

Shot on film, edited on video, and transferred to video to show on Showtime. I went to the producers and asked “Are you going to cut the negative?” They said “Why would we do that?” “Well, if you cut the negative, you have the film. If you don’t cut the negative, you have a D1 master.” The reason why I call it a D1 is because there’s going to be a D2, and a D3, and a D4, and so on. They keep copying this piece of material until it falls apart. They said “Well, we don’t want to spend the money to edit all these movies on film. Forget it!” So they threw out of all the materials except for one movie: Robert Rodriguez’s “Roadracers,” which they wanted to distribute theatrically.

They cut the negative on that one, but that was the only one that they cut the negative on. So now they only exist as these old-fashioned video masters which can never be bumped up to Blu-ray, because they’ll never look good enough. What we’re running is a Beta-cam which I ran for some other festivals. But these movies are going to be lost. These are going to be lost movies, as are many TV shows from the ’90s. Because they don’t exist on film, they only exist on video. They have to constantly be re-bumped up, and after a certain point, the video masters just can’t take it. This whole digital thing … “Oh, put it in the Cloud. It’ll be safe forever.” Bullshit. If it doesn’t exist on film, it doesn’t exist. Which includes my last two films, which won’t exist in 30 years because they’re entirely digital.

That series is an interesting contrast with “The Movie Orgy,” which exists only on film. Many filmmakers say that they only see the imperfections in their films when they rewatch them. But “The Movie Orgy” seems like it was designed to change with each viewing. Do you ever rewatch it?

Its imperfections are fairly apparent. When we put it together, it was seven hours. It was done because there had been a very successful revival of the 1943 Batman serial, which they ran in its entirety in one sitting. All 15 chapters. People came in, they got pizza, they got up, they came back. It was sort of a “being” of the time. I don’t know if you know what that means, but people would get together and just be. I had a great time at it. I mounted something like that myself at the Philadelphia College of Art, and that went quite well. Then my friend Jon Davison and I—who were film collectors—had success to all these pieces of film, and commercials, and all sorts of stuff.

So we decided to put on our own movie orgy, which we ran at NYU. We rented a bunch of movies that were psychotronic in nature, and we figured out where the good parts were. We’d take one reel of a movie, and run it up to the part where it got boring. Then cut to another reel of our own stuff, and it’d switch over to our projector. Then we would switch to an entirely different movie. So there are five different stories being told at the same time interspersed with all this trivia. It was a huge hit. People went out, got high, ordered food, got higher and recognized all these landmarks from their childhood: TV shows, kid’s shows that hadn’t been on for years that they had vague memories of … it became quite the phenomenon.

The Schlitz beer company came to us and wanted to sponsor us: we’d take this thing around to college campuses, and they’d sell beer. We went to various college campuses with our one print—our 16mm, all 2,000-splices print—which we would have to ride. Every time there was a lighting change, we’d have to change focus. The sound levels would go up and down. But there was no mixing involved, there was no correction. It was all splices, hand-spliced. And eventually it started to wear out. There’s only so many sprockets you can fix before it’s too late. We eventually retired the film. And then about 15, 20 years ago, I saw the film sitting in my vault, and I thought, “I wonder if this would have any relevance today to anybody.” I had a video made (because I didn’t want to run the original). And we screened it at this New Beverly theater. It was a phenomenon; it was the event of the year. People were lined up around the block. They had heard about the movie from word-of-mouth, and so it became this legend. People loved it, so we took it around to various places. It’s played the Museum of Modern Art, which doesn’t even have pop corn. We’ve played festivals all over Europe, where people don’t even know what the movies involved are all about. And it still seems to play. I put together as much of it as I could … I’ve only got about 4.5 hours now. And I kept updating it, so there’s no real extant version of it. This is the current version.

People ask, “Why don’t you put a video out of it?” Well, first of all I don’t own anything on it. Some of it is unidentifiable. And, more importantly, this only works with an audience, with a crowd. It’s an experience movie, it’s not a movie movie. If you took “The Clock” home, and sat and watched it at home … it’s the group experience that makes it what it is. If you take that away, it’s not a 3D movie, it’s a 2D movie. The only times we show it is with crowds at place like this. And we don’t charge, because we can’t, because we don’t own it. It’s something.

Several things in your career, including “The Movie Orgy,” the trailers you cut for Roger Corman and most recently your website “Trailers from Hell” suggest that trailers are just as much a part of the films they advertise. What do you think working on editing trailers for Roger Corman movies taught you about advertising and its role in moviemaking?

I can’t say it taught me much about advertising, but it taught me how to edit. I had only edited “The Movie Orgy,” and it was in 16mm. So here I had this big upstanding 35mm moviola, and 35mm film prints, and I thought: “Jeez, films are big!” [both laugh] I had to teach myself. And because this was a no-holds barred era, with the ratings system just coming in, you could get away with things that you were never able to before. We tended to just give away all the stuff in the trailers, all the action scenes, all the sex scenes.

And then when I started to make my own movies, I started to realize that this is a very bad way to sell a movie. If you give them everything, there’s nothing to enjoy when they finally see the movie. We learned a little bit more sophistication as we did more and more of these movies. But you gotta remember that the quality of a lot of the New World Pictures was … not stellar. And one of the tricks was: if the movie was poorly photographed, you didn’t want to show too many shots from it. If it had bad sound, you didn’t want to use too much dialogue. So we came up with these animations, and tricky ways of selling a movie with shots that really weren’t in it. We would completely falsify plotlines and put the in the trailer.

Like that exploding helicopter shot.

Exploding helicopter shots, yeah. These things would be seen on TV spots the weekend that the picture opened, and people would go to the movie, and by the time they came home, the TV spots weren’t running any more, and they didn’t remember that there wasn’t an exploding helicopter in the movie. It was a great introduction to filmmaking in general, and certainly one of the reasons I was able to make my first movie in ten days with no money using footage from movies we had done trailers from.

Let’s fast-forward to my favorite of your movies: “Gremlins 2.” I’m not a fan of this trend where commentators say “X predicted Donald Trump.” But if it brings people to see “Gremlins 2” …

Well, any way to plug your movie. We didn’t exactly discover Donald Trump, he was there to be discovered. He was a very prominent figure. I just thought of him as an entrepreneur and a builder. We needed a character like that for the film, but that wasn’t enough. We needed a character who had his own cable station, too, a guy who was involved in society. So we combined him with Ted Turner. That character is probably a little closer to Ted Turner because there are more specific references to Turnerisms, like that end of the world video. Ted actually had an end of the world video ready to go; we found that out from someone in his company. We put together our own end of the world video, though we eventually got to see Ted Turner’s version later. Ours is much better. If the world is going to end, just put on that reel of “Gremlins 2,” and watch that.

I assume your version has higher production values.

Well, we had get great stock shots. All I can remember of Ted’s version is a marching band and a sunset [laughs].

Would you say “Gremlins” was harder to make than its sequel, just because there was no road map? Or did the expectations put on you for “Gremlins 2” make it more difficult to wrap your head around?

It was harder to make “Gremlins.” Because nobody trusted what we were doing, and we didn’t know what we were doing, and we were invented the technology as we went along. That was a much more difficult movie to make. Also, we got carte blanche to make “Gremlins 2.” They said “Do what you want, we just want a Gremlins movie.” And it was very successful. Most studios just want a copy of the first picture. “Give us the first picture with a different cast.” Or: “Give us the first picture with a different setting.” Just make sure it’s the first picture, because that’s the one they liked. We didn’t have to do that. Of course, we wanted to change it from the small-town, and go into the big city, bring it up to date, make it modern. It was the beginning of the ’90s, so we have all these automation jokes, and futuristic jokes, and jokes about society in general. It’s a satire, whereas the first one is a spoof. There’s a difference. “Gremlins 2” was a very rewarding movie to make. It’s probably the most expressive of my personality. The movie it’s running with tonight was it’s inspiration: “Hellzapoppin.” Which is a movie nobody can see anymore because of right’s problems. It’s an unjustly unknown major comedy that was incredibly influential for me.

I also wanted to talk a little about “Small Soldiers” since you’ve joked that it’s like “Gremlins 3” in some ways. Unlike “Gremlins,” “Small Soldiers” was made after the advent of PG-13. But pressure to get a PG rating on “Small Soldiers” was so great because of Burger King’s sponsorship …

Initially, they said they wanted an edgy movie for teenagers. So ok, we made that. Then Burger King came aboard, and they said that they want a kid’s movie. And it became difficult to make a kid’s movie out of the material that we had on-screen. Luckily—or unluckily for them—the MPAA said “Well, there’s a scene where the toys put drugs in someone’s coffee. That’s an instant PG-13.” So it then becomes a PG-13. I think the studio would have preferred a PG. I think they were happy it wasn’t an R. But they did prevail upon me to cut out a lot of violence. Or as Denis Leary calls it in the movie: “action!”

At the end of the movie, the house explodes, but you never got to see it. We blew it up, but they didn’t want to show it. So there were a lot of compromises as to the level of intensity that you could have in the second half of the movie. Otherwise: it’s a nice enough movie. I think they had hopes it was going to be the beginning of a series, and it wasn’t. But my beef was always that you don’t charge people $7.50 to go see a movie with “small” in the title, especially in a world where everything’s about being a big blockbuster. The best they could come up with for a tagline was “Small Soldiers, Big Movie.”

I remember that! I was the target audience for the film, too. I was bombarded with ads, and I knew I really wanted to see it. But I remember looking at that poster, and thinking: “What the heck is this tagline … “

I know. Did you get the toys? There were toys, you know.

No, my parents wouldn’t let me.

Now they’re going for a lot on eBay.

What’s your favorite aspect of filmmaking?

I started as an editor, and I still gravitated toward editing because you make the movie three times: you write it, you direct it and you edit it. And in the editing room is where you discover what you’ve done. And sometimes what you discover is exciting, sometimes what you discover is horrifying. “Oh my God, this isn’t the movie I thought it was.” Your job is to perfect the movie it’s becoming, not necessarily the movie you started out to make.

For example, if one character starts to stick out over another, and you have a test screening, and the audience starts to like this character, and doesn’t really like this other character, who’s supposed to be equally attractive … then you start to focus the movie on the character the audience likes. Because that’s where the audience satisfaction is. Sometimes, you can do that to the detriment of your movie. If you go off on the wrong way, then you have a movie with no particular point. But editing is really the last chance to save or kill your movie. So many movies have had both done to them at that point. It’s particularly galling if a movie gets taken away from them, like the big movie that opened this weekend: “Suicide Squad.”

I had read that was [director David Ayer’s] cut, though.

No, the studio was cutting a version at the same time he was cutting his version. They tested both versions, and the studio version tested higher. It just has has a lot less of the Joker in it, apparently. I have strong feelings about test screenings. Any filmmaker who puts his rough cut in front of an audience can tell where it’s going wrong, and fix it. But to the studio, we’re not having that kind of connection. They need people to tell them things, so they hire research groups who ask special questions, sometimes weighted towards getting answers the studios want to hear.

And it just turns into this big public relations nightmare that can—and has—brought many a movie down. Just look at “The Magnificent Ambersons.” They paired it with a “Mexican Spitfire” comedy, and the audience didn’t like it. It was a college audience, and they didn’t like the movie. Rather than just run it before another audience, like in Manhattan—they chopped up the movie. This has been happening ever since. They really don’t have a lot of faith in whatever it is they’re doing. At the first sign of trouble, they panic. Sometimes the panic can be assuaged, and sometimes it can lead to ruinous versions of movies that have come out.

There are many examples of movies that have come out, and the cuts that came out are completely different than how it was intended. And of course those films sank like a stone. So the real movies never get rediscovered. Every so often, somebody goes back into “Major Dundee,” and puts together a version of the movie that’s closer to what the director wanted. And people say, “Oh, this is a lot better movie than we thought!” Most movies aren’t that lucky, and in many cases, the director’s already passed on. One of the movies I’m running at BAM is a Mario Bava picture called “Lisa and the Devil,” which never existed as an actual movie until Bava passed away. The audience thought the theatrical cut, “House of Exorcism”—which is a piece of shit; that’s what I think Bava would have said—was what Bava had intended to make. And it wasn’t. It was a bastardization of the art movie he made that nobody would distribute because it wasn’t commercial enough.

There are happy ending sometimes to these kinds of stories, and many of us are still hanging on, hoping we find that missing footage from “Bride of Frankenstein,” or the “Magnificent Ambersons” footage, or whatever. Every so often, something does turn up. So you just don’t know. In Czechoslovakia they find in a mine shaft a movie that was long thought lost. It does happen, but movies are such a minefield. There are more movies to see than there have been in my lifetime. And they are unfortunately so unknown to the majority of audiences. That’s why Trailers from Hell was created, to try to have contemporary people point modern audiences (younger people) to movies that they wouldn’t give the time of day to someone they don’t think of as a contemporary. When people come up and say “I wouldn’t have seen ‘Valerie and Her Week of Wonders’ if I hadn’t seen it on Trailers from Hell,” it makes me feel like we’re doing a worthwhile venture. This is our tenth year. We’ve got a site redesign coming up, and a lot of new commentators. It’s been very rewarding.

What do you think about theatrical gimmicks like 4DX and DBox?

The things you’re talking about are like theme park rides. I’ve done some of those films. I’ve done a Busch Gardens haunted lighthouse movie that was in 3D. They spit water at you, and you think rats are crawling on your legs, that kind of thing. That’s where that aspect of the IMAX experience is going. It’s a ride to virtual reality, which will become a big thing once they learn how to tell a story. And I love the idea of interactive movies! When William Castle was doing gimmicks, he didn’t get very many theaters to install motors in chairs for “The Tingler.” Yeah, in the big cities, but they’re not going to do it for smaller theaters. But people want more. The idea of paying your money, and going to see a square black-and-white screen was great when that was a novelty. Now, some people’s TV screens are bigger than the ones at the multiplex. So they want to get people to get into the theater, so the way they do it is to say “It’s not just a movie you can see at home.” That’s why they did 3D and Cinemascope, because you couldn’t see it at home. This is their way of keeping ahead of the curve.

But the target audience for that kind of thing is well under 30, and will probably remain so. Everyone else will have to be content with watching movies at home. Which is a sad thing because the great thing about BAM is that people get to see the movies in an environment with other people. I was at the “Gremlins” screening last night, and people were reacting with giddy wonderment. They were having the audience reactions that the movie is supposed to engender. Which makes it more fun, makes you feel like you’re having an experience. If you watch the same movie at home…it’s the same movie, but it isn’t the same experience. That’s why I wish the idea of movies with an audience wasn’t dwindling. But it’s becoming much more difficult. This is New York City. There are other places, like Chicago, and L.A. There are pockets of places where people can go see an old movie with a big crowd. But it’s not like in the ’60s, and there were revival theaters down every street. It was a paradise! You can’t even imagine. It was a limited number of movies because there were only so many movies available. And many more are available now on home video than were ever able to show in the theaters. But the environment of seeing them in theaters is what makes the difference for me. It’s like going to church.

“Joe Dante at the Movies” is now playing at BAMcinématek from August 5 – 24. Click here for more information.