“Superboys of Malegaon,” about film buffs obsessing over films and then making one of their own, is one of the most accessible and entertaining movies about the creative urge that you’ll see. It’s best not to read too much before watching it because it’s based on things that really happened, which means it takes a few turns that you expect and many more that you don’t (because life is generally not as tidy as fiction). It’s not a formally adventurous work that’s smashing the boundaries of commercial cinema or anything like that. As directed by Reema Kagti and written by Varun Grover—and set in the waning days of analog technology, circa 1998—it establishes its small-town, movie-obsessed characters and their dreams and challenges in a series of economical gestures, as a much older movie might do, then keeps going in that vein, all the way through to the end.

But in the process, a remarkable thing happens: it keeps turning into another movie, then another movie, then another movie, covering a longer span of time and a wider range of concerns than you might have expected going in, but rather than feel scattered or unfocused, it ends up feeling kinda like life itself. You never know what challenge the next sunrise might bring, but you have to meet it even if you don’t feel like it. That’s the trick, and the struggle.

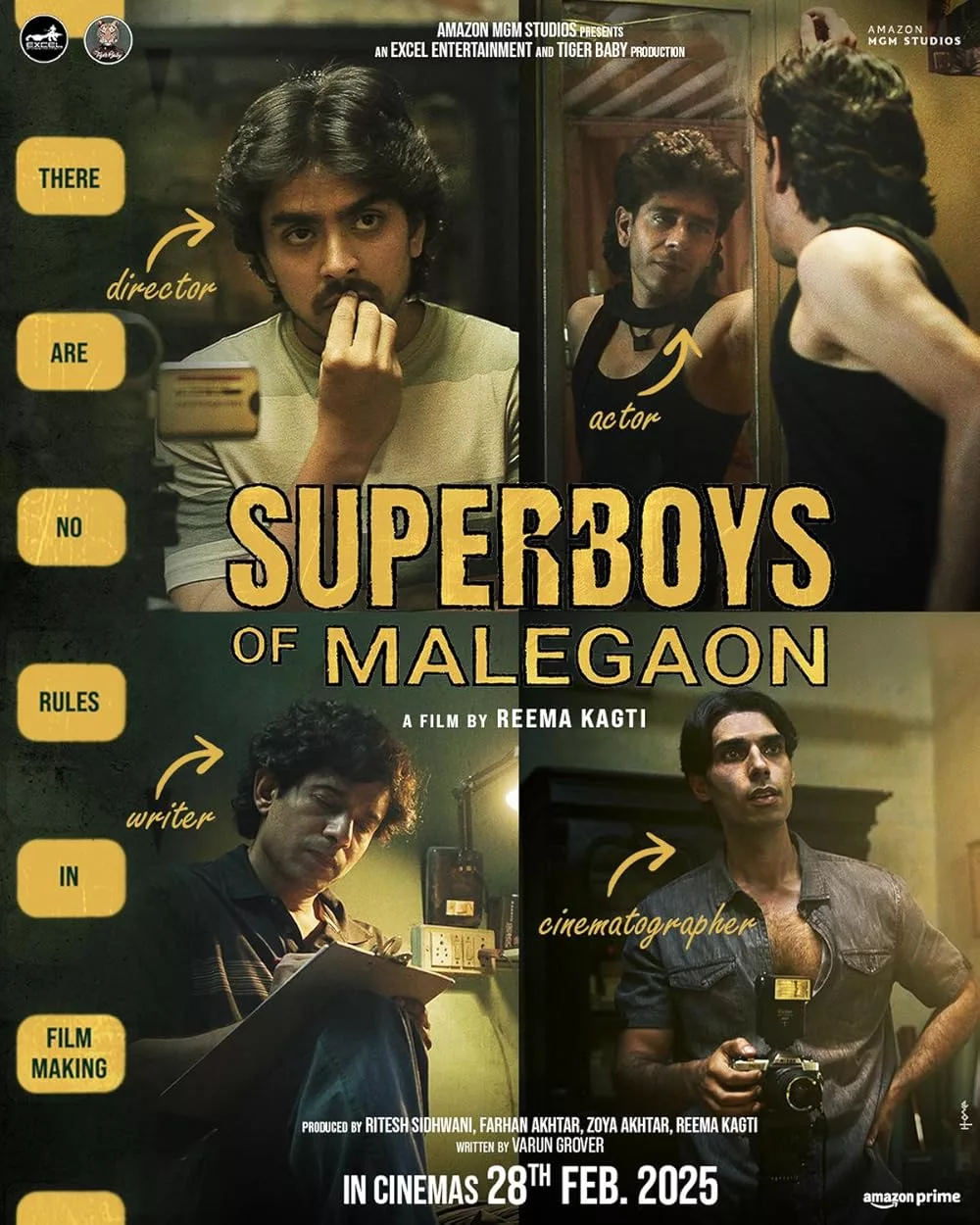

Adarsh Gourav, star of 2021’s “The White Tiger,” plays the wedding videographer Nasir, one of a duo of cinema-focused brothers who run a micro-cinema that shows mashups of film history classics, including silent movies by Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton. Malegaon is a city in the Nashik District of Maharashtra State in India, which is, to put it mildly, not known as a center of cinema. A small theater across the street shows current movies, and there are lines out the door, but the brothers’ place rarely draws more than a handful of ticket buyers because the locals want Bollywood spectaculars made in Mumbai. (“We’re the only ones showing Chaplin and Keaton in Malegaon,” Nashir says defensively. The reply: “Why are we showing these films? Did Chaplin’s dying mother ask you to show her son’s films?”)

After the police break up a screening for showing copyrighted movies without authorization (even though they are not, strictly speaking, the actual works) Nashir gets the bright idea of making a low-budget spoof of Bollywood hits like “Sholay” right there in Malegaon, then showing it in the microcinema. This gambit is partly about keeping the doors open but mainly a fulfillment of urges that were already percolating inside locals whose lives revolve around the cinema.

Nashir and his brother, who handprints the theater’s posters and other signage, are smart, driven young men, but they aren’t writers, so Nashir asks local journalist and wannabe-screenwriter Farogh (Vineet Singh) to handle those duties. The cast and crew assembles itself from there. Some of the sequences are expected but foolproof and therefore welcome (like a montage of auditions for key speaking roles, which has never, in all of movie history, failed to get laughs) while others are unexpected for the way in which they show how art must intertwine with life and all of its unglamorous daily responsibilities and economic realities.

At one point the cinematographer has to pack up his gear and do a wedding in the middle of the shoot, because those bills aren’t going to pay themselves. When the production needs a cash infusion halfway through, Nashir accedes to his producer’s scheme to put a commercial for a locally produced brand of matches in the film itself (product placement!), sparking the wrath of Farogh, who rightly accuses Nashir of compromising the integrity of his vision. “So just say you want money,” Farogh says. “I’ll steal some. But don’t spoil your picture.”

What’s fascinating about the latter scene—and many others related to the artistic process and the artists who participate it—is that even when the arguments get heated and uncomfortably personal, even hurtful, nobody is completely right or completely wrong. Everyone is allowed to make valid points that can’t be entirely refuted. Farogh is pretentious and inflexible but also representative of a purist mindset that should be cherished and nurtured because without it, there would be no real art. Nashir is a shortsighted and impulsive person who pulls his friends into his dream without thinking of what it costs them, but he’s got the kind of drive you need to make new things, and the others mostly don’t. Cinema is a popular art form that had its origins in the industrial age and is a part of the larger economic engines that drive society, sometimes for the worse. The most successful filmmakers find a way to balance those forces and hit that sweet spot between giving the audience what it wants and what they never knew they wanted, and keeping it all personal and idiosyncratic without disappearing up their own bums.

“Superboys of Malegaon” is itself a dramatization of this interplay of agendas and ideas. It has a bright spirit and infectious energy, thanks partly to Sanchin-Jigar’s ear worm of a score and editor Anand Subaya’s crisp cuts, which keep things moving inevitably forward, and the first half especially might remind older viewers of that golden period in the 1990s and early aughts when home video presale money allowed for the funding of lots of low- to medium-budget comedy dramas about somewhat regular people scrambling after a dream, like “The Full Monty, ” “Tampopo,” “Big Night,” “Brassed Off” and “Be Kind Rewind” (which would fit beautifully on a double-bill with “Superboys”).

The second half takes a more melancholy turn but remains engaging, even when it becomes heart-wrenching and then inspirational. By the end, the project has reached back much further into cinema history and connected itself with the kinds of character-based ensemble comedy-dramas (even melodramas) that old Hollywood directors like Frank Capra and Frank Borzage (look them up if you are not already fans!) used to make. While watching those sorts of movies, you’re surprised by how many different modes and moods are contained in the work and how dark things can sometimes get, and equally surprised by how deftly the movie portrays the characters confronting unexpected developments in their lives, then trying to integrate them with their dreams rather than letting the dreams die.

This is a funny and beautiful movie with a big heart. You will see yourself in it.