Gavin Hood’s “Eye in the Sky” is a thrilling document of modern warfare, an uneasy slice of life about a drone strike involving various people across the globe who never see each other. Helen Mirren plays Colonel Katherine Powell, a UK military official who wants to strike on a house in Kenya inhabited by terrorists on her Most Wanted list; an immediate action that faces an endless amount of complications. She has a POV inside the house, thanks to local spy Jama Farah (Barkhad Abdi) and the cameras he has managed to get inside. But along with needing clearance from various politicians in the “kill chain” of command (as organized by Alan Rickman‘s Lt. General Frank Benson), the drone strike (to be carried out by a Las Vegas-based pilot played by Aaron Paul) raises questions of acceptable collateral damage, legal cause and propaganda, especially when a little girl sets up a bread stand within explosion range. With many shifting pieces, “Eye in the Sky” explores the step-by-step process of drone strikes, along with the horror of deciding on life and death from only a satellite feed.

Hood originally hails from Johannesburg, South Africa, which was the setting for his breakout film in 2005, “Tsotsi.” After that film won the Oscar for Best Foreign Language film, Hood began working in the studio system, helming “Rendition” in 2007 and “X-Men Origins: Wolverine” in 2009, the latter featuring the early iteration of Ryan Reynolds’ “Deadpool” character. In 2013, Hood adapted Orson Scott Card’s famous novel “Ender's Game” for a young-adult feature that has gone wildly under-appreciated, especially with its frank presentations of violence and death as aimed at a middle school crowd.

RogerEbert.com spoke with Hood about his latest film, in which he shared his interest in an “ethical-dilemma-driven” piece, spoke about his similar thematic interests in “Ender’s Game,” offered two animated reenactments of Helen Mirren’s performance from “Eye in the Sky,” and much more.

Let’s start at the beginning. What excited you the most about Guy Hibbert‘s script?

I was reading scripts and looking for the next film to do, and I read Guy Hibbert’s script. I think I had the same experience that I hope the audiences are having, in that I was turning the pages and I was simply drawn in. All of the sudden I was hooked and thought I knew what to do, and then turned the page and thought, “Maybe I don’t know what to do.” It became increasingly tense and increasingly complex. I got to the end and I wanted to talk to someone, and there was no one to talk to, because I had read a script [laughs]. So, I thought if I wanted to talk to somebody about this subject, maybe audiences will want to talk to each other, and I thought it might be a good collective experience as both a thriller and something that leaves you with something to talk about afterwards.

And then I was curious about so many things, because I knew you could stop and pause this film at any moment and spin off into multiple conversations. You can pause on Aaron Paul’s character and have a discussion about drone pilots and PTSD, and what does this mean, this bizarre world of moving between home and work and back to home—which has been covered, I think people are becoming aware of it. But then the whole propaganda question, that one British politician raises, where you think she’s the maternal woman who doesn’t want to kill the kid, and then all of the sudden she says, “I’m not sure we shouldn’t sacrifice 80 lives at the hands of the enemy rather than one at our hands to win the propaganda war.” You can stop the film and go, “Okay, this is all about blowback and strategy questions.” There were just so many questions the film raised that I thought would be fun for a film to make, and I learned a great deal in the process, which made for an interesting few years.

I think the questions that Guy’s script has beautifully raised are supported by the fact that he’s not reaching for an argument—these are the arguments and discussions that are happening among policy makers, lawyers, the military, human rights organizations. We had a wonderful screening last night, and a professor of history and politics was there moderating, and I was nervous. He’s an expert, but he loved [the film], and he felt that we touched on the points that are being discussed. I hope it brings what seems like a mysterious subject to the general population, and we de-mystify it. This is it. What you see in the film is accurately researched, and I also really like the fact that Guy’s script doesn’t tell you what to think. I hope it presents you with multiple points of view, and allows you to be the jury and decide what to think.

For me, I previously hadn’t considered the extensive process of drone strikes. Your film brings to light how complicated each decision is, and the various levels of command, AKA “the kill chain.”

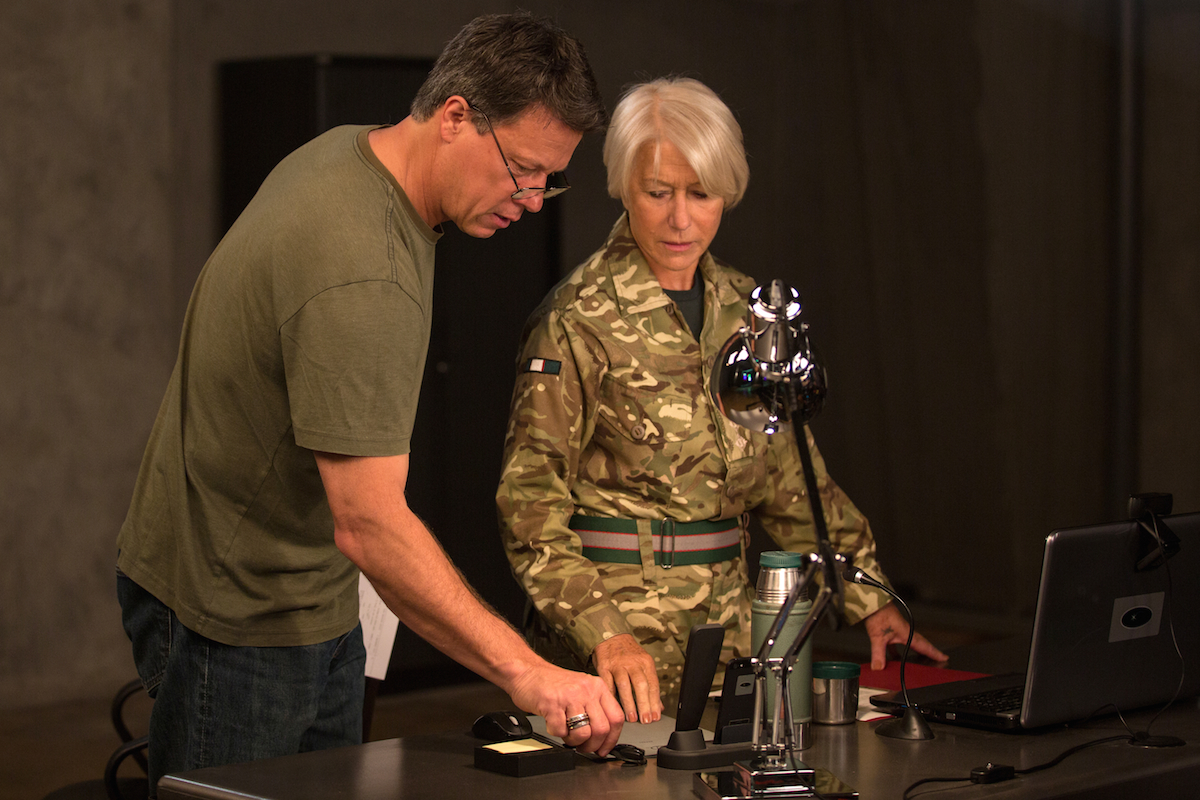

Which is actually how it works. And it was tricky to do, because just as a filmmaking challenge none of the actors were on set at the same time. We didn’t have a huge budget, so I had to shoot with Helen Mirren first for the first eight days, and it’s a credit to her acting and her presence. She’s working with a green screen. I didn’t have any of that footage of what happens with the little girl. I had a red cross with a green screen, saying, “This is where the target house is, over here is where the little girl will be,” and then I’m just describing to her what’s happening. I asked her, “Are you going to be okay with this?” She said, “Gavin, look. My job is to use my imagination. You tell me where to look, and you describe what’s happening, and I’ll do my best to internalize that.” I think she does that amazingly well. And the same with Aaron, Alan Rickman. Everybody shot in isolation, they didn’t ever meet each other. And in some ways that was good, because that’s the way it is in this modern warfare. She’s in London, he’s in Las Vegas, and they don’t meet each other except via phone lines. It’s a bizarre world you’ve been in.

Alan Rickman has a very striking role in the movie, in part for how he brings a gravity and sense of humor to such emotionally intense proceedings. When we first meet his Lt. General Frank Benson character, he’s just trying to buy the right doll.

I’m really pleased you asked, because obviously I wish Alan was here to talk about the film. He was so intelligent, he was so funny and so warm, and he genuinely was interested in the subject, and so he had a lot to say about it. When we went out to him, I wasn’t at all sure that he’d take the role, because if you look at it just as a role, it’s an ensemble piece. There’s no actor that gets to be the glory person, and his role is really just this liaison between his commanding officer Helen Mirren and these politicians who are sweating it. You can imagine that you could have had a performance who was a general who is frustrated, and what Alan brings to the role is this amazing ability to be absolutely emotionally truthful, and at the same time make you laugh. And that would just be the slightest shift of expression, the most subtle twist on a line. He also gives that character which could have been very one-dimensional a full personality with very little material to work with. And in fairness, that’s in the writing.

The trick with what Guy and I were honing this thing, was how can we know as much as possible about this character in as quickly as possible? In the scene with the doll, the idea for that comes from research where folks that cope better in this business are people who can compartmentalize. In this new warfare, you’re not on the battlefield fighting with your mates and then coming home. You’re at home, then you’re on the battlefield, five minutes later. You drive a car to the office, it’s all on video for you, and then you go home. And Aaron Paul’s character is struggling to do that, and Alan Rickman’s character has figured out how to do that. So, how do we create the most efficient way of telling that story, given that we don’t want it to get in the way of the central narrative? I think he delivers really well, with minimal material and carefully honed material. He makes you laugh, and that’s a good thing if the laughter is coming out of the truth of the situation. It’s not like, “Oh, let me make a funny joke here.”

I feel like his character could have easily become the Old Crusty General we see in so many war movies. The same goes with Helen Mirren’s character, Colonel Katherine Powell.

Did you know that Helen Mirren’s character was originally a man? I think for half of any of film, casting is critical. Especially in a film like this where there is a very strong narrative, a very strong plot line, it’s not a character-driven piece, it is an ethical-dilemma-driven piece, which is hard to do. So how you can ensure that the characters are simply not just mouthpieces for a point of view, how can you ensure that despite the fact that they represent different ethical positions, that they are nevertheless fully-rounded human beings with minimal time to do that? One of the things you do is you make sure you find actors who have rich personalities of their own. So, when Helen Mirren steps on screen, she just has to wake up for one moment to her husband snoring, and you’ve bonded with her. We’ve all experienced that in some way. That’s good writing, that’s good acting, and it’s very efficient. This is a woman who has a husband and not much of a life and a dog, and oh my goodness, she’s a colonel. We get just enough of her backstory without hopefully slowing the narrative down. And then the fact that Helen is able to, like Alan, take a line where, or even no line, when she’s waiting for that young man to rework the Collateral Damage Estimate for him, there’s a moment where, I love it, she just walks away … [Hood stands up and walks away from me, his back to me and then turns around slightly with a small look of desperation] like, “Will you please hurry up? We don’t have much time, young man.” And you kind of laugh, but you also know exactly what kind of person she is. You wouldn’t want to get in a fight with this lady. If you were a kid, she would be your pushy mum, you know? So, I thank her for that.

But I should answer the question about why I had recast the part for a woman instead of the man. One of the reasons is that, forget about whether she is male or female, as an actor she brings this incredible intelligence and this powerful presence. She is powerful. There’s that wonderful moment where she walks up to the young lawyer, who is a heads-and-shoulders taller than her, and she just says [Hood gets close to my face] “Are you asking me or telling me?” And so, we wanted that. I think the scene works better because an edge of humor comes into it because she’s smaller than him. If the role were played by a man, it would simply be an intimidating scene. It wouldn’t have that extra layer. I think as a director, you’re always asking, “How many layers can I get out of a moment? Can I get a layer of irony, can I get an edge of humor, while still delivering intimidation? How can I enrich the moment and make it more than one thing?” And that’s like eating a good meal as opposed to a bland, single piece of bread.

But also, what was so great about having Helen was that I hope that it takes the story to a broader audience. If she were a male character, it would look like a guy’s movie. And I crassly, frankly want this film to appeal to men and women. So having Helen and Alan, hopefully it’s not about gender, it’s about the ethical dilemmas that are raised that men and women should discuss as equals.

Watching this movie about many different moving parts and immediate, fatal decisions, there feels to be a parallel here about being a film director. The idea of the kill chain even sounds like a studio system.

I hadn’t thought of it that way. Well, I’ll say that when I first started in this business, we started shooting on film, and the film needed to be sent away for processing and then you saw what you shot a day or two later. So the studio, back in wherever they were, were seeing your rushes and dailies a couple days after you were done. So if they really didn’t like something, it was a big deal. Now, you’ve got 12 producers on set, all watching monitors in real time. And so as a director I do feel a certain additional pressure because they’re watching what you’re doing while you’re doing it. I guess if you’re involved in the business that Helen Mirren’s character is, it’s that much more frustrating. But we’re still just making a movie, I mean, we’re making a movie. She’s engaged in real world, life-and-death situations, and I think that is the frustration for some of those military commanders: “My God, when did this become a battle by committee? In real time, these politicians are watching what I’m doing, that wasn’t always the case.”

How did the world’s response to “Ender’s Game” influence what you wanted to do with this film, especially as the two are similar in their focuses on the morality of remote warfare?

I don’t know, I think I’ve wanted to compartmentalize the two. But one of the reasons I wanted to make “Ender’s Game” is because I have young children, twin eight-year-olds, and it felt to me that so many of the films that they watch are about simplistic themes of good vs. evil, and the good guys always wins and the bad guy’s a bad guy and the good guy can do no harm. And that’s not the real world works. What I liked about the “Ender’s Game” theme is that it asks young people to ask themselves whether they have the capacity to do evil, and where will they find themselves? Will they reach for their better selves? We understand that in life there is a grey zone, and you have to find your own moral compass. Well, “Eye in the Sky” is the same themes, I suppose, but in the real world, for a grownup audience with no punches pulled.

Do you feel you’ll be going back to studio projects?

I think what I’ve learned … when I started in my filmmaking career I made smaller films, and because they were smaller I guess the financial stakes were lower. I had more control of what I was doing. When I entered the big studio system, I think I was not as prepared as I am now for what you talk about which is the amount of politics, the amount of fear, and the amount of people involved in the decision-making process. It can tend to water things down when you’re trying to satisfy 15 different viewpoints, and you’re being pulled in many directions. I’d been through things where there’s a writer’s strike and notes are coming from the studio out of panic, and that is not the best way to make a movie. So, yes, I will do big films and small films, but only, going forward, if I know that the script is solid, solid, solid before you start. There are so many moving parts anyway that you don’t want that shifting under your feet. For me, it’s really about what are the themes that the film explores, and I’m more cautious now about what I choose because it does take up two to three years of your life.

These very layers you’ve mentioned about “Eye in the Sky” were what made “Ender’s Game” particularly exciting, and different for a big budget film.

Which is a risky thing because most big studio movies want to give the audience those more simple things. Goodie wins. And the other thing that I really loathe in movies is that shtick of, “Our hero is harmed by some bad guy, and the movie is about getting revenge, and at the end you’ve got revenge, and the world is set right.” Well, guess what? The world isn’t usually set right. What was fun about “Ender’s Game” and this film is that you got to explore some more complicated themes.