How strange, a movie where a bad man becomes better, instead of the other way around. “Tsotsi,” a film of deep emotional power, considers a young killer whose cold eyes show no emotion, who kills unthinkingly, and who is transformed by the helplessness of a baby. He didn’t mean to kidnap the baby, but now that he has it, it looks at him with trust and need, and he is powerless before eyes more demanding than his own.

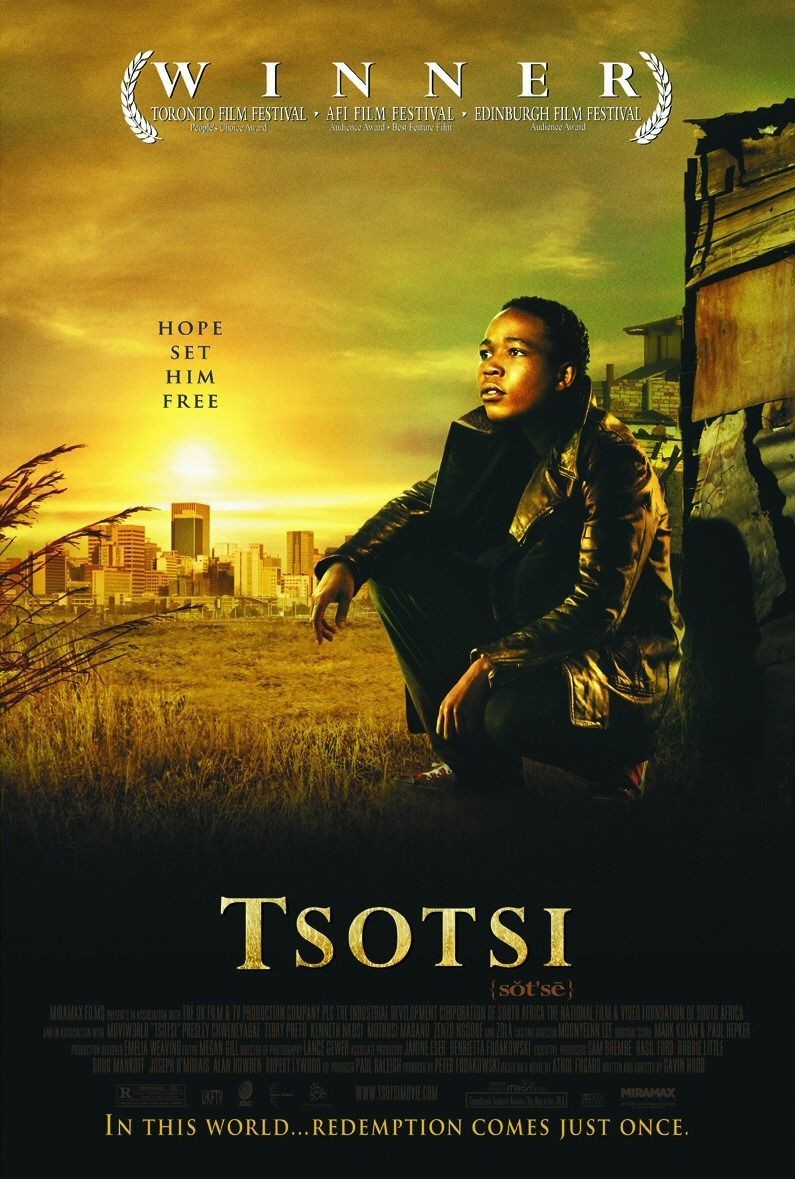

The movie, which just won the Oscar for best foreign film, is set in Soweto, the township outside Johannesburg where neat little houses built by the new government are overwhelmed by square miles of shacks. There is poverty and despair here, but also hope and opportunity; from Soweto have come generations of politicians, entrepreneurs, artists, musicians, as if it were the Lower East Side of South Africa. Tsotsi (Presley Chweneyagae) is not destined to be one of those. We don’t even learn his real name until later in the film; “tsotsi” means “thug,” and that’s what he is.

He leads a loose-knit gang that smashes and grabs, loots and shoots, sets out each morning to steal something. On a crowded train, they stab a man,- and he dies without anyone noticing; they hold his body up with their own, take his wallet, flee when the doors open. Another day’s work. But when his friend Boston (Mothusi Magano) asks Tsotsi how he really feels, whether decency comes into it, he fights with him and walks off into the night, and we sense how alone he is. Later, in a flashback, we will understand the cruelty of the home and father he fled from.

He goes from here to there. He has a strange meeting with a man in a wheelchair, and asks him why he bothers to go on living. The man tells him. Tsotsi finds himself in an upscale suburb. Such areas in Joburg are usually gated communities, each house surrounded by a security wall, every gate promising “armed response.” An African professional woman gets out of her Mercedes to ring the buzzer on the gate, so her husband can let her in. Tsotsi shoots her and steals her car. Some time passes before he realizes he has a passenger: a baby boy.

Tsotsi is a killer, but he cannot kill a baby. He takes it home with him, to a room built on top of somebody else’s shack. It might be wise for him to leave the baby at a church or an orphanage, but that doesn’t occur to him. He has the baby, so the baby is his. We can guess that he will not abandon the boy because he has been abandoned himself, and projects upon the infant all of his own self-pity.

We realize the violence in the film has slowed. Tsotsi himself is slow to realize he has a new agenda. He uses newspapers as diapers, feeds the baby condensed milk, carries it around with him in a shopping bag. Finally, in desperation, at gunpoint, he forces a nursing mother (Terry Pheto) to feed the child. She lives in a nearby shack, a clean and cheerful one. As he watches her do what he demands, something shifts inside of him, and all of his hurt and grief are awakened.

Tsotsi doesn’t become a nice man. He simply stops being active as an evil one, and finds his time occupied with the child. Babies are single-minded. They want to be fed, they want to be changed, they want to be held, they want to be made much of, and they think it is their birthright. Who is Tsotsi to argue?

What a simple and yet profound story this is. It does not sentimentalize poverty or make Tsotsi more colorful or sympathetic than he should be; if he deserves praise, it is not for becoming a good man but for allowing himself to be distracted from the job of being a bad man. The nursing mother, named Miriam, is played by Terry Pheto as a quiet counterpoint to his rage. She lives in Soweto and has seen his kind before. She senses something in him, some pool of feeling he must ignore if he is to remain Tsotsi. She makes reasonable decisions. She acts not as a heroine but as a realist who wants to nudge Tsotsi in a direction that will protect her own family and this helpless baby, and then perhaps even Tsotsi himself. These two performances, by Chweneyagae and Pheto, are surrounded by temptations to overact or cave in to sentimentality; they step safely past them and play the characters as they might actually live their lives.

How the story develops is for you to discover. I was surprised to find that it leads toward hope instead of despair; why does fiction so often assume defeat is our destiny? The film avoids obligatory violence and actually deals with the characters as people. The story is based on a novel by the South African writer Athol Fugard, directed and written by Gavin Hood.

This is the second year in a row (after “Yesterday”) that a South African film has been nominated for the foreign film Oscar. There are stories in the beloved country that have cried for a century to be told.

Ebert’s coverage of “Yesterday” and other South African films at the Toronto Film Festival can be found here and elsewhere in the Toronto festival section of the site.