This is being done in our name. People who are suspected for any reason, or no good reason, of being terrorists can be snatched from their lives and transported to another country to be held without charge and tortured for information. Because the torture is conducted by professionals in those countries, our officials can blandly state that “America does not torture.” This practice, known as an “extraordinary rendition,” was authorized, I am sorry to say, under the Clinton administration. After 9/11, there is reason to believe the Bush administration uses it frequently.

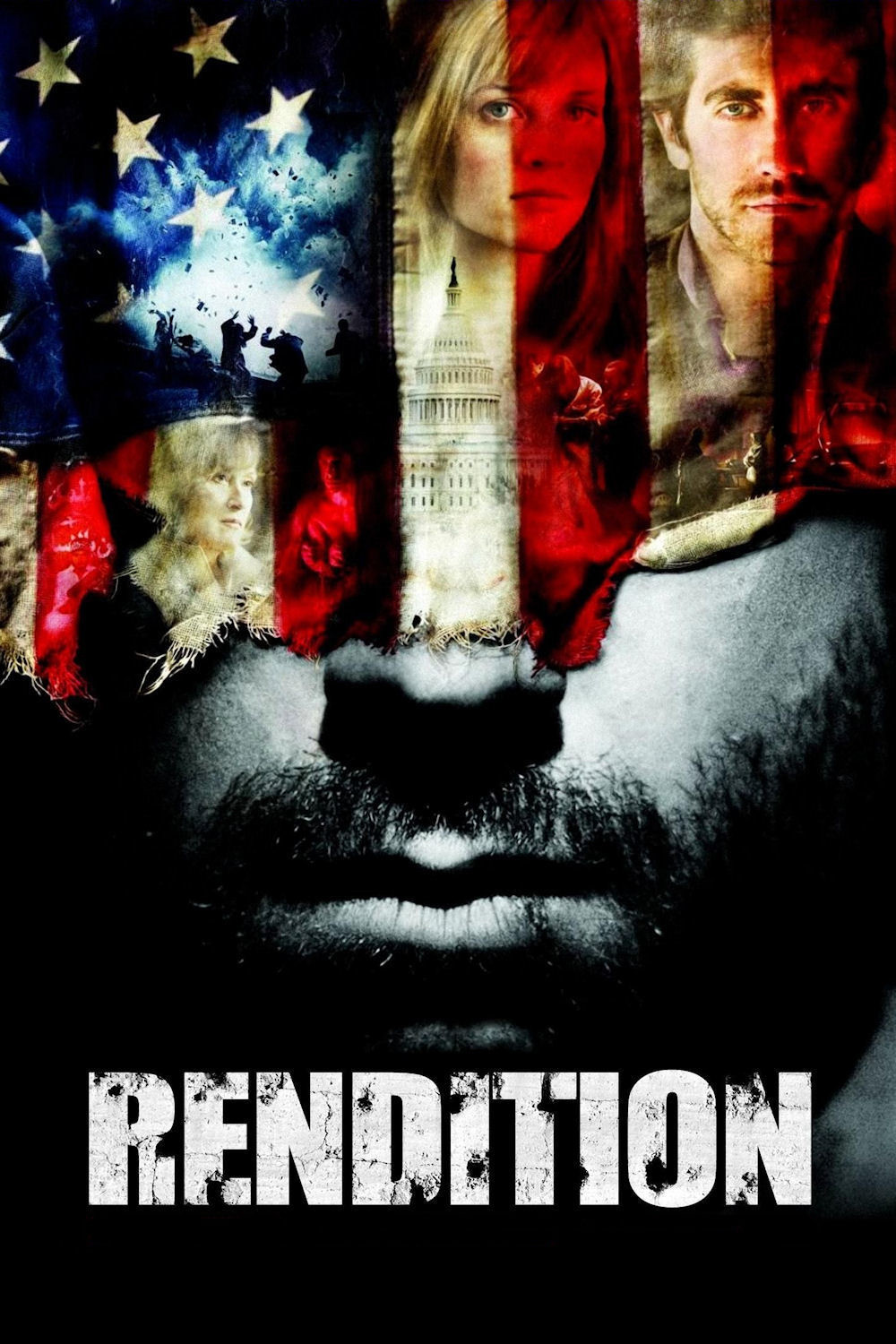

Director Gavin Hood‘s terrifying, intelligent thriller “Rendition” puts a human face on the practice. We meet Anwar El-Ibrahimi (Omar Metwally), an Egyptian-born American chemical engineer who lives in Chicago. He and his wife, Isabella (Reese Witherspoon), have a young son, and she is in advanced pregnancy with another child. After boarding a flight home from a conference in Cape Town, South Africa, Anwar disappears from the airplane, his name disappears from the passenger list and Isabella hears nothing more from him.

He was taken from the plane by the CIA, we learn. His cell phone received calls from a terrorist, or perhaps from someone else with the same name, or perhaps it was stolen or lost and used by somebody else. His background is clean, and he passes a lie detector test, but he’s hooded, flown to an anonymous country and placed in the hands of an expert torturer named Abasi Fawal (Igal Naor). Anwar’s frantic wife is told he never got on the flight, although she later discovers his credit card was used for an in-fight duty-free purchase.

If there is one thing history and common sense teach us, it is that if you torture someone well enough, they will tell you what they think you want to hear. As successful interrogation experts have patiently explained to Congress, much more useful information is obtained using the carrot than the stick. Yet Anwar is held naked in a dungeon, beaten, nearly drowned, shocked with electricity, kept sleepless, shackled. Does it occur to anybody that he is more likely to “confess” if he is not a terrorist than if he is?

The movie sets into motion a chain of events caused by the illegal kidnapping. Isabella, played by Witherspoon with single-minded determination and love, contacts an old boyfriend (Peter Sarsgaard) who is now an aide to a powerful senator (Alan Arkin). Convinced the missing man is innocent, the senator intervenes with the head of U.S. intelligence (Meryl Streep). She responds in flawless neocon-speak, simultaneously using terrorism as an excuse for terrorism and threatening the senator with political suicide. Arkin backs off.

Meanwhile, in the unnamed foreign country, we meet a CIA pencil-pusher named Douglas Freeman (Jake Gyllenhaal), who has little experience in field work but has taken over the post after the assassination of his boss. His job is to work with and “supervise” the torturer Abasi. This he does with no enthusiasm but from a sense of duty. He is not cut out for this kind of work, drinks too much, broods, has discussions with Abasi, who is an intelligent man and not a monster.

How this all plays out has much to do with Abasi’s daughter, Fatima (Zineb Oukach), who is secretly in love with a fellow student not approved of by her family. All these human strands, seemingly so separated, eventually weave into the same rope, in a film that builds its suspense by the uncoiling of personalities.

It is now so well-established that the United States authorizes the practices shown in this film that when President Bush goes on television to blandly deny it with his “who, we?” little-boy innocence, I feel saddened. He may eventually be the last person to believe himself. What the film documents is that we have lost faith in due process and the rule of law, and have forfeited the moral high ground. Reading some of the reviews after I saw this film at the Toronto Film Festival, I was struck by a comment by James Rocchi on Cinematical.com: “Anytime someone tells you that you can’t make an omelet without breaking eggs, immediately demand to see the omelet.”

Gavin Hood, the South African-born director of “Rendition,” first came into wide view with the wonderful “Tsotsi” (2005), which won the Academy Award for best foreign film. Now comes this big, confident, effective thriller with its politics so seamlessly a part of its story. Next for him: “X-Men Origins: Wolverine,” based on the “X-Men” character. I hope we don’t lose him to blockbusters. A film like “Rendition” is valuable and rare. As I wrote from Toronto: “It is a movie about the theory and practice of two things: torture and personal responsibility. And it is wise about what is right, and what is wrong.”