Italian neorealism—and the later cinematic new wave movements across Europe it helped influence—understood that there’s great drama to be found in everyday events. Will the man trying to support his family recover the stolen bicycle he needs to do his job? Can the family of fishermen continue their increasingly unstable work? It’s the simplicity of the story combined with the excellence of the filmmaking—again, often deceptively simple—that makes it work.

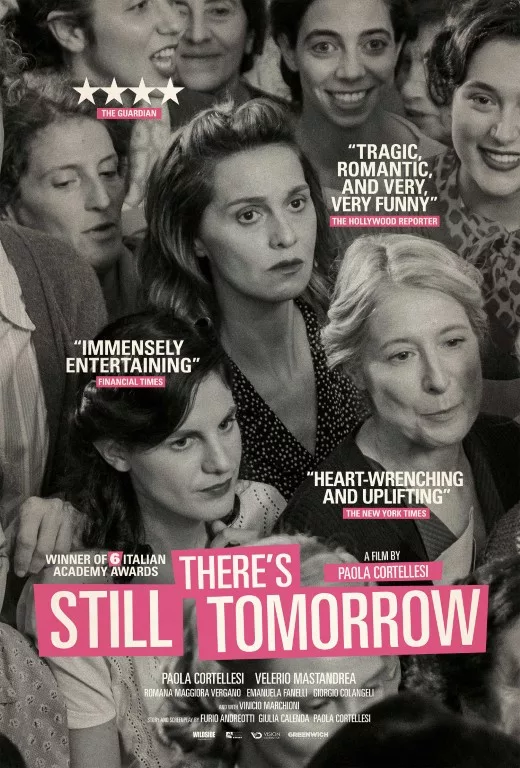

Paola Cortellesi mixes this old-school approach with current-day feminism in “There’s Still Tomorrow,” a period comic drama about a put-upon housewife (Cortellesi) discovering her agency. The best parts of Cortellesi’s film embrace the inherent drama of otherwise mundane occurrences. It’s when the star, director and co-writer takes unexpected swerves into territory that doesn’t mesh with the established tone that things go awry.

In post-war Rome, Cortellesi’s Delia cares for her abusive husband Ivano (Valerio Mastandrea), her spiteful father-in-law Ottorino (Giorgio Colangeli) and three children in a shabby basement apartment. Delia hustles, working several different jobs and selling her own clothes to help make ends meet in addition to putting food on the table. There’s hope for upward mobility in oldest daughter Marcella (Romana Maggiora Vergano) who plans to marry Giulio (Francesco Centorame), the son of a well-to-do family of business owners.

Delia’s struggle through her thankless days is changed by the arrival of a mysterious letter. Slowly, she starts gaining confidence. She takes an increased interest in Marcella’s future, and whether or not that future should include Giulio. Most importantly, she starts having conversations with her friend Marisa (Emanuela Fanelli) that make it sound like she’s considering leaving Ivano.

Cortellesi’s examination of Delia’s life follows a straightforward neorealist format—black and white photography, period-appropriate music—except when it doesn’t. Early on, as Delia leaves the house and walks to her first job, the orchestral score switches to American blues music. Later on, during a scene where Delia’s trying to escape her family, a needle drop of OutKast’s “Bombs Over Baghdad” fits the emotion of the scene so unexpectedly well that it earns a solid laugh.

Cortellesi is putting a modern, female lens on a historically male form of cinema storytelling, which is commendable. However, those modern elements are so inconsistent and jarring that they take the viewer right out of the experience. Another inconsistent touch—though not inconsistent with the genre—is the occasional use of surrealism, which shows up here in the form of musical numbers. The issue isn’t that these moments exist, but how. They primarily depict Ivano’s physical abuse of Delia, reducing their fights to choreographed dances. These scenes rob the couple’s unhappy and exploitative relationship of its very real danger, putting a twee filter over something that shouldn’t have it at all.

These choices make it difficult to understand what Cortellesi wants to accomplish. Is “There’s Still Tomorrow” supposed to be a feminist critique of neorealist tropes? Is it an attempt to make an older cinematic form feel fresh and relevant? A final-act turn takes the film into history lesson territory that suddenly feels like we’re being sneak-fed cultural vegetables and make the whole movie feel unnecessarily self-righteous.

These elements also take away from a story that’s compelling on its own. There’s oodles of tension, for example, in Delia preparing and serving a Sunday lunch for Marcella’s prospective husband and in-laws. Will the food be good enough? Will Delia’s foul-mouthed sons and belligerent husband make Marcella look bad? Can the family successfully keep the crass Ottorino from leaving his bedroom and messing up the whole affair? All the pieces Cortellesi wants to balance—comic farce, dramatic stakes, historical cultural expectations and class struggle shown through a feminist perspective—operate on full capacity in this scene. It makes all those other flourishes even more confounding by comparison.

The parts of “There’s Still Tomorrow” that work suggest a film that could’ve been truly special. It’s even possible to see the parts that don’t work as well—those needle drops, for instance—reworked and made more consistent to create an experience that honestly comments on the evolving nature of how we understand stories like Delia’s, and who gets to tell them. This potential is nearly lost under a pile of choices that try too hard to make relevant a story that doesn’t need bells and whistles to communicate its value. In trying to put her own spin on neorealism, Cortellesi loses sight of the things that made the genre enduringly effective.