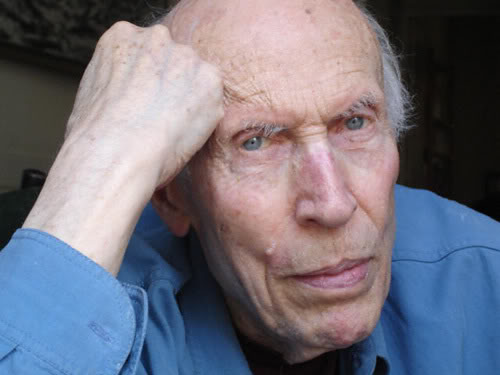

We’ve lost a gentle and wise humanist of the movies. Eric Rohmer 89, one of the founders of the French New Wave died Monday Jan. 11 in Paris. The group , which inaugurated modern cinema, included Jean-Pierre Melville, Francois Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, Claude Chabrol, Agnes Varda, Alain Resnais, Jacques Rivette and Louis Malle. Melville, Truffaut and Malle have died, but the others remain productive and creative in their 80s.

Rohmer’s characters arrived at moral decisions in their lives, usually through romance, often with warm humor. Few directors have loved people more: Their quirks, weaknesses, pretensions, ideals, and above their hopes of happiness. In 27 features made between 1959 and 2007, not a single Rohmer character was a generic type. All were originals.

Rohmer followed in the spirit of his countryman Balzac, mapping his works around central themes. He made six “Moral Tales,” six “Comedies and Proverbs” and his “Tales of the Four Seasons,” along with 11 films outside category. His films often illustrated a proverb, but it was impossible to guess which one until he surprised you at the end.

He first made an impression in America with “My Night at Maud's” (1969) and “Claire's Knee” (1970). Those “moral tales” often involved a moment before marriage when a man’s thoughts turned to other tempting choices. The choices were revealed through indirection, in films ostensibly about something else. As I wrote in a 1971 review: “If I were to say that ‘Claire’s Knee’ is about Jerome’s desire to caress the knee of Claire, you would be a million miles from the heart of this extraordinary film. And yet, in a way, ‘Claire’s Knee’ is indeed about Jerome’s feelings for Claire’s knee, which is a splendid knee.” That unobtainable knee, for Jerome, represents all the delights he is surrendering.

Rohmer was a taste worth acquiring. Arthur Penn gave Gene Hackman this line in his “Night Moves” (1975): “I saw a Rohmer film once. It was kind of like watching paint dry.” Some moviegoers might agree with that, but not Penn, whose own “Bonnie and Clyde” has been described as the New Wave washing ashore in America.

Rohmer was born as Maurice Henri Joseph Schérer. He created his professional name by combining those of the Austrian director Erich von Stroheim and the English novelist Sax Rohmer. He was the editor of Cahiers du Cinema, the legendary French film magazine which launched a generation of young critics into filmmaking, and finally followed his proteges into full-time directing in 1963.

His films usually cost little, did not have huge grosses, and were treasured for their delightful sensibility. In 2001, the year he won a rare Golden Lion for lifetime achievement from the Venice Film Festival, I wrote: “A Rohmer film is a flavor that, once tasted, cannot be mistaken. Like the Japanese master Ozu, with whom he is sometimes compared, he is said to make the same film every time. Yet, also like Ozu, his films seem individual and fresh and never seem to repeat themselves; both directors focus on people rather than plots, and know that every person is a startling original while most plots are more or less the same.

“Rohmer is the romantic philosopher of the French New Wave, the director whose characters make love with words as well as flesh. They are open to sudden flashes of passion, they become infatuated at first sight, but then they descend into doubt and analysis, talking intensely about what it all means. Because they’re invariably charming, and because coincidence and serendipity play such a large role in his stories, this is more cheerful than it sounds. As he grows older Rohmer’s heart grows younger, and at 81 he is more in tune with love than the prematurely cynical authors of Hollywood teen romances.”

Among his best-known titles were “Chloe in the Afternoon” (1972), “A Good Marriage” (1982), “Summer” (1986), “An Autumn’s Tale” (1998), “Pauline at the Beach” (1983), and “Rendezvous In Paris” (1996).

His final film was “The Romance of Astrea and Celadon” (2007). Did he intend it as his last? It was a wild departure, set in 5th century Gaul and involving shepherds, shepherdesses, druids and nymphs. Yet it was a Rohmer, all right, with Astrea and Celadon destined to love but kept apart by misunderstandings, coincidences and second-guessing themselves. As always, there was a satisfactory outcome.