The French New Wave began circa 1958 and influenced in one way or another most of the good movies made ever since. Some of its pioneers (Melville, Truffaut, Malle) are dead, but the others (Godard, Chabrol, Rivette, Resnais, Varda) are still active in their late 70s and up. And Eric Rohmer, at 88, has only just announced that “The Romance of Astrea and Celadon” may be his last film.

It doesn’t look like typical Rohmer. He frequently gives us contemporary characters, besotted not so much by love as by talking about it, finding themselves involved in ethical and plot puzzles, at the end of which he likes to quote a proverb or moral. His films are quietly passionate and lightly mannered.

But then, so is “Astrea and Celadon,” even if it’s set in 5th century Gaul and involves shepherds, shepherdesses, druids and nymphs. The story was told in a novel by Honore d’Urfe, Marquis of Valromey and Count of Chateauneuf, who published it in volumes between 1607 and 1627 — running, I learn, some 5,000 pages. The film version must therefore be considerably abridged at 109 minutes, although it leaves you wondering if the novel ran on like this forever.

The movie does rather run on, although it is charming and sweet, and is perhaps too languid. It is about two lovers obsessed with love’s codes of honor. That is, curiously, the same subject as Rivette’s 2007 film, “The Duchess of Langeais,” made when he was 84. The characters seem perversely more dedicated to debating the fine points than getting down to it. Rivette has them talking to each other; Rohmer has them fretting while separated.

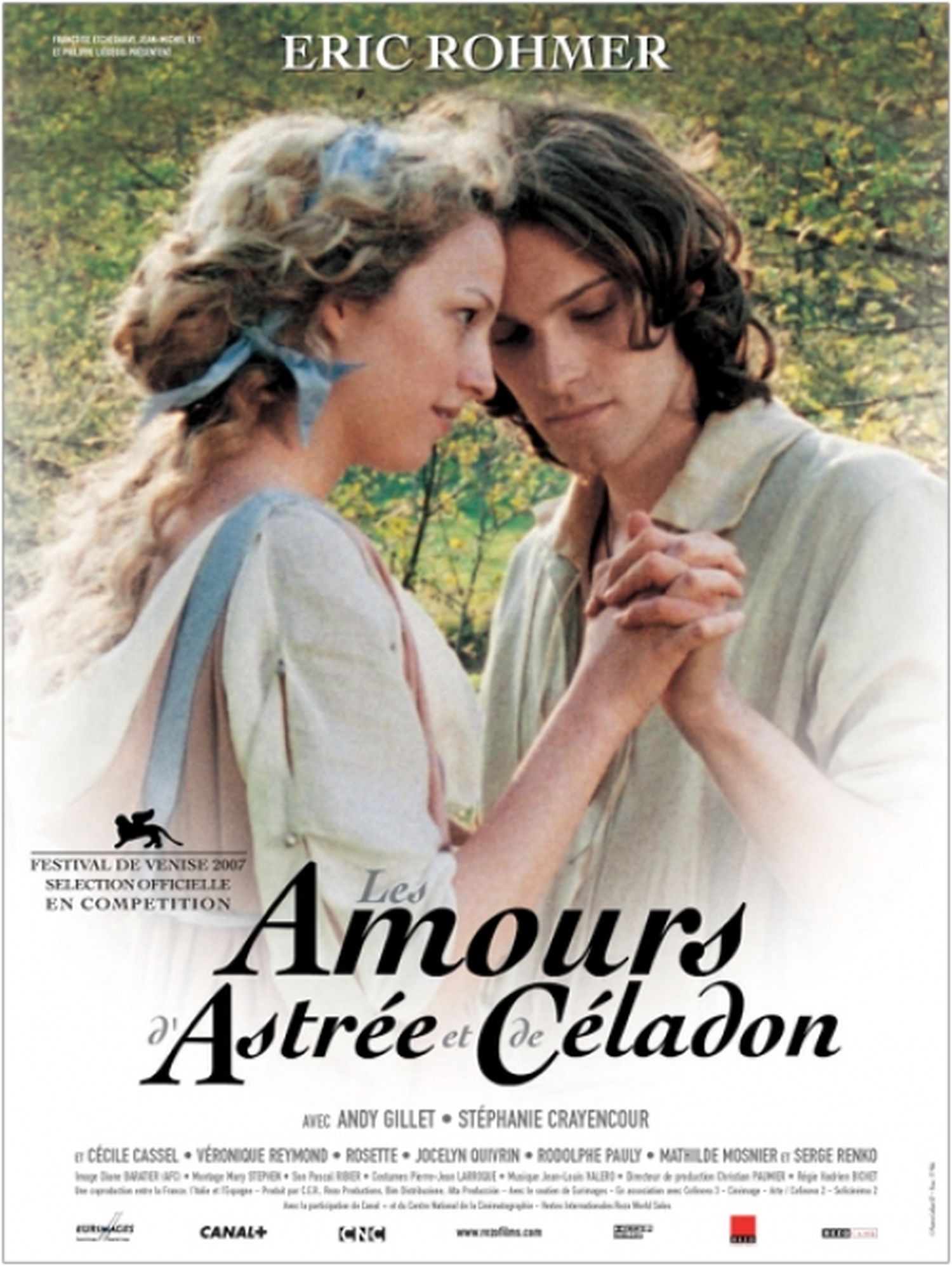

The story is told in pastoral woodlands and pastures, and along a river’s banks. We meet the handsome Celadon (Andy Gillet) and the beautiful Astrea (Stephanie Crayencour), shepherds and in love, not long before a tragic misperception breaks Astrea’s heart, and Celadon hurls himself into the river in remorse. Believed by Astrea to be dead, he is fished out by the statuesque nymph Galathee (Veronique Reymond) and her handmaidens, and kept all but captive in her castle. He pines, sworn never to be seen by Astrea’s eyes again, while the two lovers debate the loopholes in romantic love with their friends. They also debate such matters as whether the Trinity corresponds to the Roman gods, and sing, quote poetry and mostly seem to ignore sheep.

A Druid priest convinces Celadon to disguise himself as a girl and infiltrate Astrea’s inner circle, creating much suspense, mostly on my part, as I kept expecting Astrea to exclaim, “Celadon, do you actually think you can fool anyone with that disguise?” But they play by the rules, and then things pick up nicely when they break them.

This would not be the Rohmer film you would want to start with. I’ve seen most of his films, and my first was “My Night at Maud's” (1969), about a long conversation about everything but love — which is to say, about love.

Rohmer, I think, delights in these dialogue passages, as they allow him to see his characters more carefully than in your usual formula, where courtships seem to be conducted via hormonal aromas. Sometimes his approach is sexier. The knee in “Claire's Knee” fascinated me more than entire bodies in countless films. Why Rohmer decided to end with this film, I cannot say. Perhaps after 45 years of features, he had heard it all.