Paris is a city for lovers not because you can love better in it, but because you can walk and talk better in it. Lesser cities with fewer resources require their lovers to spend too much time loving, which tires and bores them, while in Paris the whole city is foreplay. It cannot be a coincidence that although we have the word “meeting” in English, we also borrow the French word “rendezvous.” A rendezvous is to a meeting as a rose is to a postage stamp of a rose.

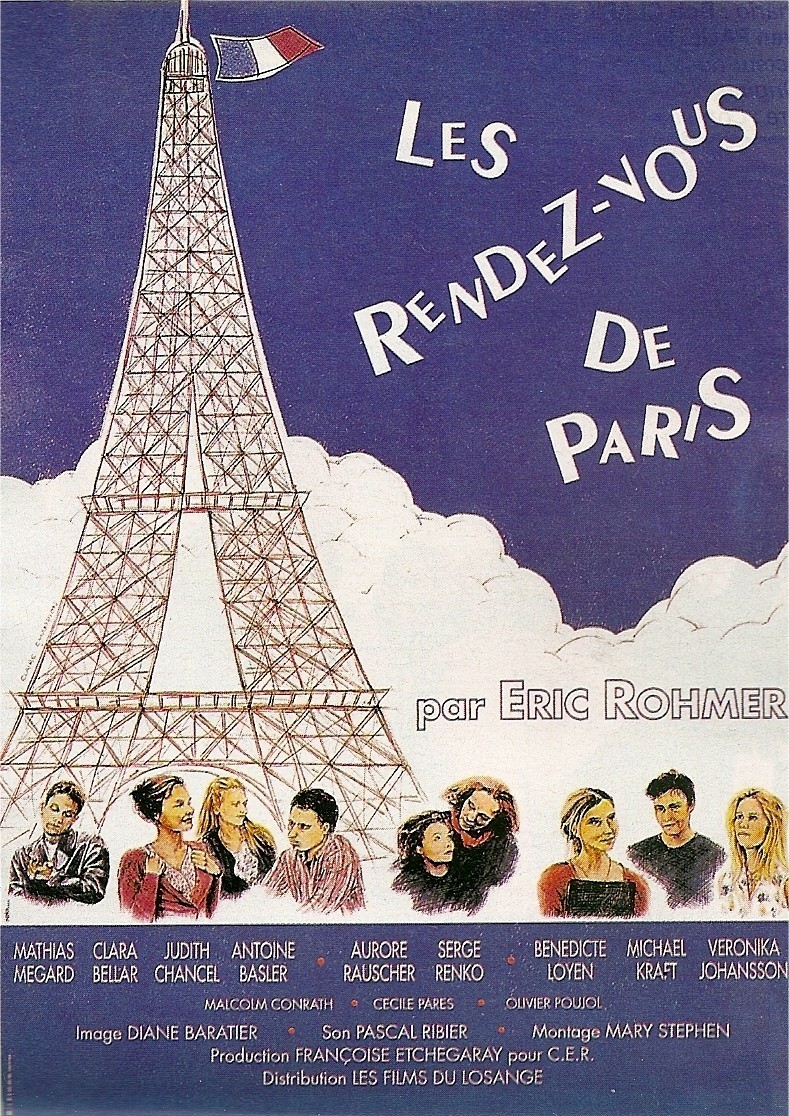

Eric Rohmer, who is now in his 70s, has dedicated most of his career to making films about men and women talking about love: the flirtations, the suggestions, the analysis, the philosophy, the quirks, the heartfelt outpourings, the startling revelations.

“Rendezvous in Paris,” which tells three stories in one film, is one of the best of his works. In it there are no sex scenes, and you could even make the case that there are no lovers–or two, at the most. Paris is such an inspiration for these characters that they play lovers even when their hearts aren’t in it. Ideally, you should have your true love at your side for walking through the parks, sitting on benches, and having deep conversations. But if that is not possible, then you should annex whomever is available, and pretend.

In the first story, a girl (Clara Bellar) is told her boyfriend (Antoine Basler) is cheating on her–seeing another girl at times when he claims he is “busy.” Walking through the market, she is approached by a stranger (Mathias Megard) who has become instantly attracted to her, but is on his way to the dentist. Can they meet later? Yes, she says–at the cafe where she’s been told her boyfriend is having his secret rendezvous. The outcome of this story, which I will not reveal, is typical Rohmer in that she’s wrong about both men–and wrong in two different ways about the second.

In the second story, a woman (Aurore Rauscher) leads her would-be suitor (Serge Renko) on a series of daily walks through Paris, while they talk and talk about love. She is in the process of breaking up with her former lover, and tells this new candidate with brutal frankness: “I used to love him more than I do you now, but I don’t love him anymore.” Finally they have almost talked themselves into a position where they have to make love or stop talking. Then she discovers that her former lover has a new woman in his life. This makes her own new lover unnecessary, since only if the old lover still cared about her would he (and she) care about her new lover. The more you think about this logic the more French it becomes.

In the third story, an artist (Michael Kraft) has a visitor (Veronika Johansson) who bores him, so he suggests a visit to the nearby Picasso museum. At the museum, he notices a woman (Benedicte Loyen) looking at a painting. He explains the painting to his own date, loudly enough so the other woman can hear him, which is the point. (Someone once said that all female speech is explanation and all male speech is advertisement.) He succeeds in ridding himself of the first woman and catches up with the other woman in the street, only to discover she is on her honeymoon. But she asks to be shown his paintings, and in his studio their conversation takes a painfully analytical turn. In an exquisite twist, he is later stood up by the first woman.

Did you spot the two real lovers? They are the woman from the first story and the man she is told is cheating on her. Of all the dialogue in this film, they have the least. Is that the point? That talk is seduction, and becomes redundant after it serves its purpose? I don’t think Rohmer is that simple. I think he believes that love is love and that flirtatious conversation is an entirely separate pleasure, not to be confused with anything else.

What the people in “Rendezvous in Paris” are really saying, underneath all of their words, is: “I am not available. You are not available. But let us play at being available because it is such a joy to use these words and tease with these possibilities, and so much fun to be actors playing lovers, since Paris provides the perfect set for our performance.” Rohmer splendidly illustrates the theory that Parisians possess two means of sexual intercourse, of which the primary one is the power of speech.