Nobody ever seemed to know what Dusty Cohl did for a living. He was a lawyer, and it was said he was “in real estate,” but in over 30 years I never heard him say one word about business. His full-time occupation was being a friend, and he was one of the best I’ve ever made.

Yes, he was “co-founder of the Toronto Film Festival.” That’s how he was always identified in the Toronto newspapers. And he founded and ran the Floating Film Festival, one of the great boondoggles, on which Dusty and 250 friends cruised for 10 days while premiering films and paying tributes to actors and directors. There was no reason for the floater except that if you were Dusty’s friend, you floated.

But beyond those titles, from which he made not a dollar, he was, simply, a phenomenon of friendship. He didn’t want anything from you. He lived to be a friend, and he wanted his friends to know each other, and he liked to put people together so good things would happen. He considered himself at one degree of separation. “When he was young, he was a social director at a resort in the Canadian Catskills,” his wife Joan told me once. “I don’t think he ever really left the job.”

Dusty died about 3 p.m. Friday, Jan. 11 at Sunnybrook Hospital in Toronto, of liver cancer. He was 78. He was surrounded at the end by family and friends. He left Joan, his wife of 56 years; his children Karen, Steve and Robert; five grandchildren, and uncounted happy memories. In 2003, he was named a member of the Order of Canada, the nation’s highest civilian honor.

But who was he, and how did I meet him? One day in 1977, when I was a stranger at the Cannes Film Festival, I was crossing the famous terrace of the Carlton Hotel, and was summoned by name to the table of a man with a black beard, wearing blue jeans, a Dudley Do-Right t-shirt and a black cowboy hat studded with stars and pins. How did he know who I was? He knew who everybody was.

Dusty was the nucleus of a group of Canadian and American film people, heavily weighted toward film critics. In those days his circle included Charles Champlin of the Los Angeles Times, Kathleen Carroll and Rex Reed of the New York Daily News, Andrew Sarris of the Village Voice, Richard Corliss of Time, and his longtime buddy George Anthony of the Toronto Sun. There was a method to his madness. He wanted us involved with the film festival.

A few years earlier, Dusty and Joan had been on holiday on the French Riviera, and found a parking space smack dab in front of the Carlton during the Cannes festival. Sitting on the terrace, surrounded by festival-goers, Dusty asked, “Why doesn’t Toronto have a film festival?” Joan replied, “You’ll probably start one, Dust.” And he did.

In the early years, Toronto was far from its present eminence. We headquartered in a hotel where Dusty and the other organizers held a morning press conference to not announce so much as predict, with fingers crossed, what would happen that day. He almost forced the festival into being, by calling in favors from friends, including the leading Canadian directors Ted Kotcheff and Norman Jewison, young director Atom Egoyan, and actors like Helen Shaver and Donald Sutherland. He raised money from cronies at the morning coffee hour where he presided. He twisted arms to bring in film critics, because he knew press coverage was the key to putting the festival on the map. In the earliest years, the festival was more covered in Los Angeles or New York than it was in Toronto, with the exception of George Anthony’s lonely voice at the Toronto Sun.

At first the big competition in the autumn was from Montreal and New York. But New York had limited seating, Montreal had political problems, and year by year Toronto grew, until in the 1990s it became the venue of choice for the premieres of the big new autumn pictures. When Dusty stepped upstairs to his newly-created post of “chief accomplice,” it was on its way to becoming the most important festival in North America, and one of the top five in the world. He was far from retired; one of his bright ideas was for Gene Siskel and me to host annual tributes, which we did for Martin Scorsese, Robert Duvall and Warren Beatty.

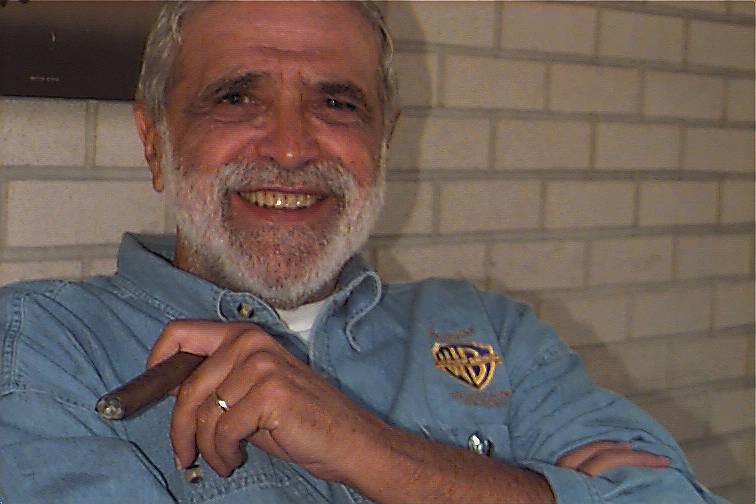

Dusty was not finished with festivals. In the 1990s he created the Floating Film Festival aboard a cruise ship on which everyone had two things in common: They liked movies, and they liked Dusty Cohl. He also kept fingers in other pies. His cousin Michael Cohl owned the company that ran the road tours of the Rolling Stones and other supergroups, and Dusty was often backstage, his cowboy hat serving as his pass. He and Michael were involved in the farewell appearance of The Weavers at Toronto a few year ago. During the week, his “office” was a chair in the office of Eddie Greenspan, the most famous trial attorney in Canada, whose client recently was disgraced press baron Conrad Black. His job? “I gossip with Eddie and we smoke his cigars.”

That left time for other assignments. When I founded my own Overlooked Film Festival at the University of Illinois eleven years ago, it went without question that Dusty and his wife Joan would be in attendance from Year One, bearing the titles “Co-Accomplices in Chief.” Most of the festival guests stayed in rooms at the student union, and Dusty posted himself in the coffee atrium to greet them, and, of course, introduce them to each other. He became close friends with such as Werner Herzog, Paul Cox, Anna Thomas, Scott and Heavenly Wilson, Gregory Nava, Bertrand Tavernier, Errol Morris, Mario Van Peebles and his father Melvin, Sturla Gunnarrsson, David Bordwell, Haskell Wexler, Lisa Nesselson, and David Poland. That started at 8 a.m. After midnight, he could be found advising on menu choices at the Steak n’ Shake, the official festival restaurant. He and Joan took off one night to attend a Champaign High School production of “Guys and Dolls,” and the next night the cast, now all friends of theirs, turned up at the Steak ‘n Shake to serenade the visiting filmmakers.

One way you knew you were a friend was when Dusty honored you with a Dusty Pin, a silver hat with a star on it. Rule was: Wear it at film festivals. At Cannes and Sundance, even on years Dusty wasn’t there, I spotted them on studio heads Michael Barker and Harvey Weinstein and half the members of the North American press corps.

Dusty Cohl made an enormous difference in my life, saving a first-time visitor to Cannes from bewilderment, introducing me to everybody, and then plopping me down in the middle of the excitement of creating the Toronto festival. When I got married, he stood up with me, and became Chaz’s confidant as well, giving her love, advice and support during my health crisis. We saw the Cohls three, four, five times a year, and talked on the phone as often as daily. He was devoted to full-time friendship, and he wanted his friends to be friends of each other. So there are hundreds, thousands, of us now.

Just today, I was able to see an advance screening of a film because Dusty pulled some strings from his sickbed in the last few weeks. Chaz and I flew down to Florida to see him over Thanksgiving, where he was weaker but still high-spirited and involved in everything. And we were able to fly to Toronto on Tuesday to say goodbye. When he took a year off from Cannes, the Carlton Hotel took a full-page ad in a festival daily showing only a cowboy hat and a cigar, with the caption, “We miss you.” Yes, we all do.

* * * *

Jim Emerson remembers Dusty Cohl here:

https://www.rogerebert.com/scanners/my-capn-dusty-cohl-1929-2008