After creating a half-century of vital and acclaimed documentaries, the Chicago-based production company, Kartemquin Films, is celebrating its first two Oscar nominations. Scoring his first Best Documentary Oscar this year is Steve James, the renowned director of “Hoop Dreams” and “Life Itself,” whose latest feature, “Abacus: Small Enough to Jail,” illuminates the criminally underreported story of Abacus Federal Savings, a family-owned bank in Chinatown, New York. James details how Abacus became the only U.S. bank to face criminal charges in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis. The picture also provides an endearing portrait of the Sungs, the family of Chinese immigrants who own the bank, as they engage in a courageous five-year-long legal battle. I interviewed James prior to the movie’s premiere at the 2016 Toronto International Film Festival, and “Abacus” has gone on to earn him some of the best reviews of his career. “Roger would be very happy about the nomination,” said James of his longtime champion. “Chaz would tell you he is very happy.”

The most powerful nonfiction short I saw in 2017 was easily Laura Checkoway’s “Edith+Eddie” (executive produced by James), which earned a nomination for Best Documentary Short Subject. It centers on the titular interracial couple in Virginia who decided to get married in their mid-90s. As their wish to remain together is threatened by forces of indifference, Checkoway’s film becomes a devastating account of how the elderly and ailing in this country are fed into the uncaring prison of institutional living, where their identities disappear and their life expectancy shortens one day at a time. The picture may only run thirty minutes, but its impact lands like a shattering sucker-punch.

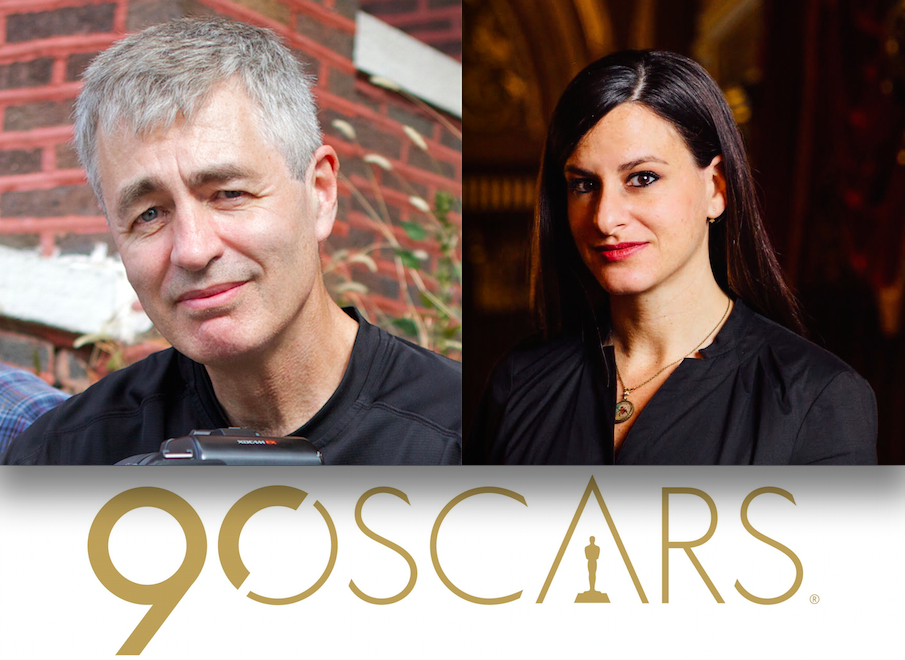

While preparing to attend the March 4th Oscar ceremony, James and Checkoway took time to chat with RogerEbert.com about the contradictions of American life, the gambles of documentary filmmaking and the reason why Oscars shouldn’t be taken too seriously.

How did you both first begin collaborating on Laura’s 2014 feature documentary, “Lucky”?

Laura Checkoway (LC): We met at a conversation among documentary filmmakers in New York City. I was making my first film at the time, and a woman named Karina Rotenstein, who became a co-producer of “Edith+Eddie,” had just met me the night before and invited me to this conversation. Steve was there and Karina literally pushed me over to meet him, because I was a bit shy. I told him that I was making a film about a young woman who was a really dynamic, outspoken person. A lot of people find her difficult, and that’s what made this film even more important to me. Yet it also made it tough to get funding. Steve could relate in his own way, and he said, “You should see my film, ‘Stevie.’” This conversation turned out to be the first of many, and he wound up watching a rough cut. He was the angel/editorial consultant that I was waiting for. He sent me the most incredible and useful notes prior to becoming an executive producer of the film.

Steve James (SJ): There were a couple things that intrigued me about “Lucky.” Laura had been filming her subject for five or six years by that point. She just decided that she was going to follow this young woman, and when Laura described her, I realized that we don’t have enough stories like this that follow the lives of difficult, not entirely sympathetic people. This is a hard story to tell because of who Lucky is, and not just because she didn’t have any money. That’s what made me think of “Stevie.” It wasn’t the fact that “Stevie” is self-reflexive, since Laura is not in “Lucky” in the way that I am in my film, though there is definitely a relationship you can sense between the filmmaker and her subject. I was reminded of “Stevie” primarily because it was a story about someone that a lot of people on the face of it wouldn’t be too interested in.

<span id=”selection-marker-1″ class=”redactor-selection-marker”></span>

LC: Stevie is from a different part of the country than Lucky, and they would seem nothing alike, yet there were so many parallels between their stories. Steve’s experience with the making of his film and how he grappled with the relationship he had with his subject—and how those lines sometimes get blurred—was really helpful to me.

SJ: There aren’t enough films about people who are damaged but not easy to pity. We never want pity for our subjects, but sometimes they inspire a knee-jerk response, resulting in audiences feeling terrible for them. Lucky is not that kind of person and neither is Stevie. People always come up to me and ask if I’d be willing to look at the rough cut of their film. I hardly ever do it. I try to be nice about it and say, “Look, I can have you send it to me, but then I might not get around to it and then I’d just feel like a heel for having asked you to send it in the first place.” It’s really rare for me to ever say yes, but there was something about Laura and about this project—the fact that she, with no money, had thrown herself into this thing for six years—that made me want to see the finished work.

LC: And thank god! [laughs]

When I interviewed Gordon Quinn for Kartemquin’s 50th anniversary last year, he told me how the company’s early films aimed to create social change, while noting that a strength of Steve’s work is his “balanced view.” How do you both maintain that balance while exploring topics that could easily be politicized?

LC: For me, so far, that’s the only way I know how to do it. I enter into every project knowing that it is ultimately all about the people, and the issues that arise through what they are grappling with in their lives during the time that I’m getting to know them. With “Edith+Eddie,” I initially thought the film was about finding love at that time in your life and what that be would like. What ended up happening to my subjects is happening to people all over, and the film turned into a look at elder rights and the legal guardianship system. But when I begin a film, I am entering into the story with an interest and a curiosity in the people who are at the center of it.

SJ: Her initial idea was to make a film about two people—one white, one black—in their 90s getting married. That alone would make me want to see the film. None of what makes this film infuriating had happened yet when she first began the project, and I think that’s often true. There is something about a situation or a person that just compels you to them. You don’t know where it’s going. You just know that they are interesting people in an interesting situation. The fact that Eddie and Edith were in Virginia—I grew up in Virginia—at their age getting married is highly unusual in any respect, but even moreso in Virginia, considering that they are crossing lines of race. But the documentary gods, if you will, dictate what your story is going to be. No matter what gets you into it, the story goes where it goes.

I have a fundamental belief that if I’m compelled and interested in someone, then you, as a viewer, will be too. It’s up to us as filmmakers to make that happen. At a film festival, someone once asked me, “How do you direct a documentary? Don’t you just show up and shoot everything?” It’s a little harder than that. [laughs] There may be exceptions to this rule, but for the most part, we don’t make advocacy films at Kartemquin. We make films that are about issues, but they are grounded in the lives of people, and the issues come out of that. We don’t actively pursue subjects that will illuminate a particular issue. It’s inside out, not outside in, and that is part of what makes the films richer and not polemical. It makes them more complex because people are complex. The issues that surround them are complex as well, and if they weren’t, we probably would’ve solved them all by now.

I’d watch a film about the Sung family even without the court case.

SJ: Exactly! If I had met them and saw the role that their bank was playing in their community, I would’ve been interested in them.

“Hoop Dreams” was nominated for Best Editing at the 1995 Oscars. It lost to “Forrest Gump,” but it was a rare honor for a documentary to be recognized in that category. What’s maddening is that the film was snubbed in the Best Documentary category, which happened to include an episode of the TV series, “American Experience.”

SJ: There’s a funny story about this. When they were going to announce the Oscar nominees, the distributor and the press folks had this brilliant idea that we would all meet at Kartemquin on the morning of the nominations. They were announced early like they are now, so everyone was at the office before 7am. Now back then, they only announced the big categories on television, and you had to look elsewhere to find the rest. At that time, there was a lot of talk that “Hoop Dreams” might get a Best Picture nomination, but we didn’t get it. Someone at Kartemquin looked up the rest of the nominees and went, “‘Hoop Dreams’ isn’t nominated for documentary.” Everybody in the room gasped. Then the person said, “But it is nominated for editing,” and everyone went, “Huh?” [laughs]

The local press was there, all ready to capture presumably the moment of the nomination, which didn’t happen, but now they suddenly had a story. Up until then it was just going to be us saying, “We’re so excited to be nominated,” but now the headline was, “Snubbed!” They wanted to get quotes, but none of this was a shock for me. I can’t speak for my partners on it. It wasn’t like I was too shocked to speak or anything. I was just like, “Whatever.” Honestly I never thought of the Oscars as more than just humorous entertainment. When I tuned in to the ceremony, I’d watch it to see what people wore. I was never like, “Oh my god, I hope ‘Midnight Cowboy’ wins Best Picture!” It wasn’t that way for me, so I didn’t have a huge amount invested in it.

We had gotten a tremendous amount of love for that film up to that time, and would go on to get even more love as a result of that. So I decided to go home without giving a quote to anybody. As soon as I walked in the door, my phone rang. I picked it up and it was Roger. He said, “This is Roger Ebert,” and I thought, ‘How did he get my phone number?’ He goes, “Are you outraged?” And I was like, “Well, Roger, I don’t know, I mean…” I launch into this lengthy answer. At one point I said, “I really want to take the long view of this,” and he kind of cut me off. “You’re not going to say anything, are you?” he asked, and I said, “Not really.” He says, “I gotta go.” [laughs] He was done, because he wanted a quote and he wasn’t going to get it from me.

LC: And little did you know how long of a view that would be.

SJ: [laughs] True! But it was kind of cool to get nominated for editing, because I was an editor. My fellow editors, Frederick Marx and William Haugse, and I walked the red carpet, but because we were doc guys, our press people had to walk in front of us and go, “The ‘Hoop Dreams’ guys! Anyone want to talk to the ‘Hoop Dreams’ guys?” And a couple people did, including Roger, of course, but not many. During the ceremony, I sat next to the guy who won, because they put all the editors together. I thought “Speed” was going to win—that’s all editing.

But so is “Hoop Dreams.” It’s three of the fastest hours I’ve ever experienced.

SJ: The only reason we got nominated is because enough editors saw our film and wanted to vote for us. Anyway, the guy won and his wife said, “This is his second one,” as he was walking up to go get it. He then let me hold the award when he came back. [laughs] It was a great anthropological experience, which is the way that I kind of want to look at this one as well.

What have this year’s nominations meant to you as well as the subjects of your films?

LC: Well, I am so earnest about everything. [laughs] It’s just so incredible, especially considering the way the film was made, which was very bare bones and independent. I took the bus to Virginia and edited on my laptop. The recognition is just that much more meaningful because of the way that the film was made. This couple was so dishonored at the end of their story, so receiving this honor feels very befitting. For us, Edith and Eddie represent all elders who deserve to live on their own terms and be treated with dignity. We’re representing all of them.

SJ: It’s too bad that they’re not alive to see this happening. But they’re captured for posterity by the film, which is a beautiful thing

LC: Edith’s daughter, Rebecca, and granddaughter, Robin, who were caring for the couple, will get to come to the ceremony.

SJ: For the Sungs, one of the reasons they went along with being filmed was not just because they felt that what was happening to them and their bank was unjust, which they did, but also because they felt like it was reflective of how the justice system and America in general tends to look down on their community, particularly communities like Chinatown that are insular and foreign. I love the fact that they referred to Americans as foreigners. When they talked to each other, they’d say, “Your son married a foreigner,” meaning an American. The family felt in their bones that this was a story that had larger meaning for their community beyond them, because they are pretty humble people. It’s a completely human reaction that when a filmmaker comes in and says, “I want to tell your story,” you go, “Oh, who me?”

You feel a little stab of notoriety and think, “Oh my god, people might hear about me.” That’s totally human and we traffic that in to some degree as documentary filmmakers without being crass about it. But I’ve never felt that from the Sungs, despite the fact that the film has been out for a long time now and they’ve been to a ton of screenings. It’s had quite a shelf life since it premiered at TIFF in 2016. I never feel like they are like, “Ooo look at us!” They love that people connect with the story and want to share stories about their own families with them. People have opened accounts in their bank that don’t even live in Chinatown, just because they want to support the mission. All those kinds of things are genuinely meaningful for them, and this nomination is an extension of that.

On a personal level, this recognition is particularly sweet for Mrs. Sung. When they announced the nominations, she and her husband were at their place in Sarasota on the East Coast. She was watching reruns of “The Golden Girls” when her daughter, Vera, called to give her the news. Then she was very excited, and told me later that day that she had been watching the Oscars for 60 years. She’s been a movie lover her whole life, and has seen all the main movies that were released over the past year. In fact, she apparently used to go through celebrity movie magazines as a young person, cut out the pictures and put her name next to the stars. Of course, never in her wildest dreams would she ever have imagined that she would have a reason to attend the ceremony in person. Given that history, it’s going to be pretty great to experience this evening through her eyes.

I haven’t been this excited about the Best Documentary category since my cousin, Jeremy Scahill, was nominated in 2014 for his film, “Dirty Wars.” For him, the experience of the Oscar ceremony felt very incongruous to his serious work as an investigative journalist. As documentarians, can you relate?

LC: I came up as a journalist in entertainment magazines, so I got my chops through doing profiles on celebrities before I veered into documentary. I was telling deep psychological stories through the vehicle of celebrities, because those were the kind of publications that I wrote for. I got into docs wanting to tell human interest stories about people who weren’t famous, so it’s interesting to have everything sort of circle back in this way.

SJ: That’s a really great question, and “Dirty Wars” was a very good film. Over the years, I’ve felt this sort of disconnect between the people I’m filming and my life in different ways. You go out to dinner on a weekend at a pretty nice restaurant and between you and one other person, you’re spending well over $100. For people I have filmed, $100 would be a pretty serious chunk of change, and I just blew it on dinner. So I think about those things. When it comes to the Oscars, thanks to you, I’ll probably be thinking about it. But because I’ve been to other black tie events, like the DGA Awards a number of times, I just try to look at it as part of the spectacle of life. I try not to be so invested in any outcome of it, which allows me to look at it through my own somewhat humorous lens.

I was just at the DGA Awards—we didn’t win—but it was hilarious because it felt like they were rushing us through dinner so we could give them rapt attention during the ceremony. They literally made us eat dinner in 20 minutes. I put my fork down to get a glass, and the waiter goes, “Are you done with that?” And I’m like, “No I’m just getting a drink.” [laughs] There were a lot of things about that ceremony that struck me as really silly, and sure, I would’ve loved to have won, but I didn’t. I also wasn’t so invested in it that it ruined my evening at all. I’ve always felt that way about the Oscars and the nomination process, so I hope that I can have that attitude about the ceremony itself.

It is kind of a spectacle of capitalism, and there’s lots of incongruity. But there’s incongruity when you read The New York Times Magazine. You’re reading an article about Syrian refugees and then you turn the page and there are ads for the highest end hotels. It’s impossible to escape the contradictions of living in America if you are of a certain status and wealth. It’s really put in your face at the Oscar ceremony for people like us who don’t tend to run in those circles, but I look at it as an opportunity just to sort of see how that world is, and try not to feel guilty about it. I understand your cousin’s a pretty intense dude, as evidenced in his movie, but I’m not that intense. [laughs]

LC: For me, this will simply be an opportunity for the message behind the films to reach a great number of people. I see it as way beyond me and even the film.

SJ: I totally agree with that as it relates to the nomination. Only one film will get to go up on the stage and if it ain’t us, that doesn’t mean our films weren’t worth making.

The 90th Academy Awards ceremony will be broadcast at 7pm CST Sunday, March 4th, on ABC.