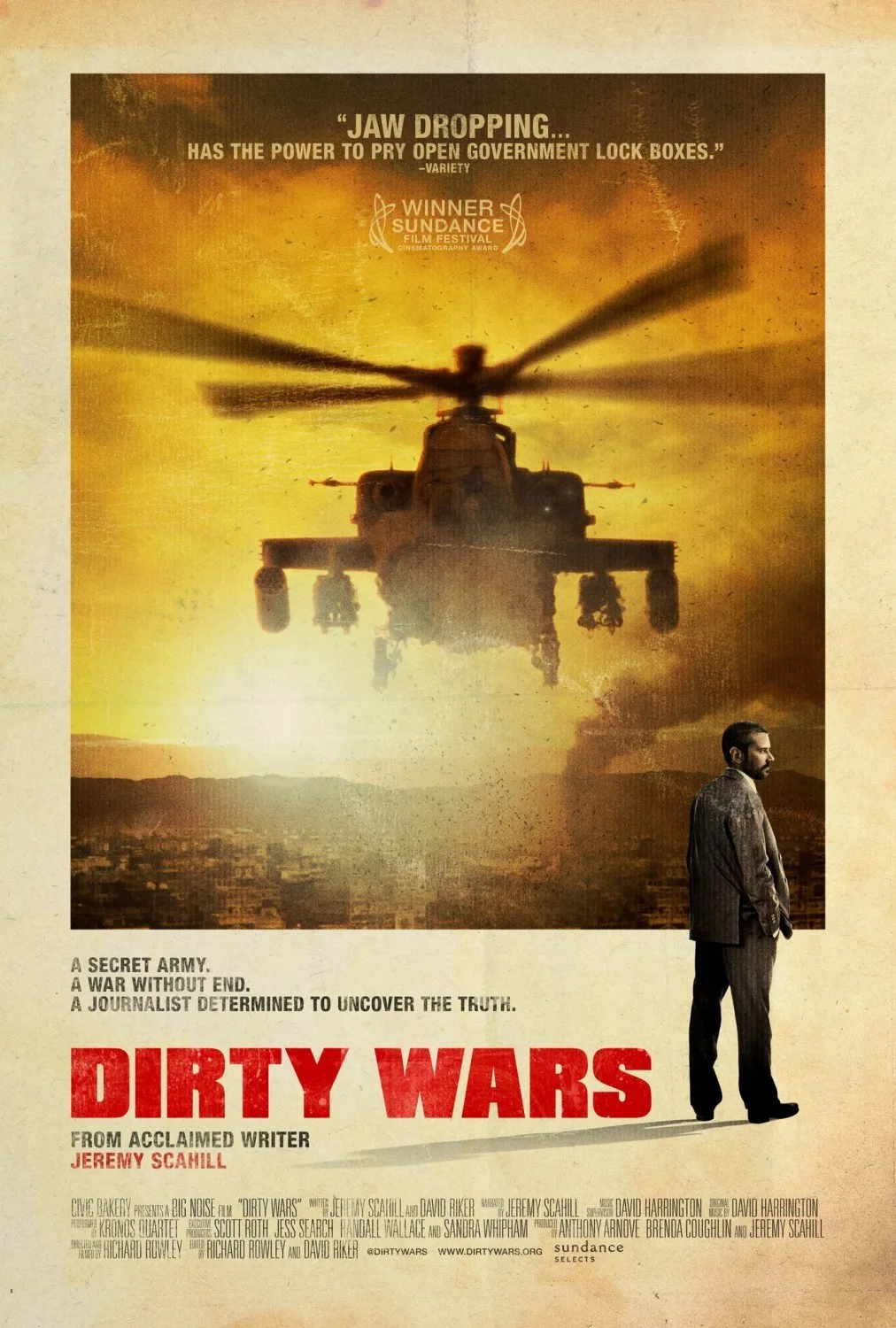

“Dirty Wars” tells many of us what we already know, that the U.S. War on Terror has become what Borat once called our “War of Terror.” The basic idea is that our elected officials are now committed to a high-tech version of terrorism, using drone strikes, home invasions, abductions and torture worldwide, ostensibly to keep America safe, but resulting in a surge of new, passionate terrorists with each civilian death.

For those American patriots who resist the idea that we might be living in a leading terror state, this film’s early stretches will probably do little to move them away from notions of American Exceptionalism or the war as a necessary evil. Director Rick Rowley has chosen a super-slick, ready-for-Vimeo storytelling style that’s somewhere between KONY 2012 and reality TV promos. Interviewees are introduced in faux surveillance photos that seem to have been passed through a Tony Scott Instagram filter. Their names and titles are spelled out letter-by-letter with a clickety-clack teletype sound effect. Every serious conclusion gets a grave Hans Zimmer-style thud or some mournful notes out of a Save the Children commercial.

If the skeptical viewer holds on tight, however, “Dirty Wars” becomes hard to swat away, no matter how much its style conveys unconscious insecurity about its assertions. Jeremy Scahill, the movie’s narrator and principal subject, is persuasive. He’s an independent journalist best known for covering the Iraq and Afghanistan wars for The Nation magazine and in his book Blackwater: The Rise of the World’s Most Powerful Mercenary Army. There are two kinds of modern war reporters, embedded and un-embedded. Scahill is the latter, rarely riding along with U.S. troops as tour guides, often venturing outside NATO-approved “green zones” to talk to the people we glimpse only fleetingly on networks like CNN: the civilians. Scahill was among the free range reporters to document Iraq war atrocities and injustices in detail, but “Dirty Wars” dramatizes his discovery of equal or greater scandals in Afghanistan.

The movie follows him as he tracks the activities of the elite military unit JSOC (Joint Special Operations Command), before the capture of Bin Laden and the subsequent hit film “Zero Dark Thirty” made its members rock stars among soldiers. Back then, the JSOC were an unnamed and unnumbered secret force that swooped down on homes in the middle of the night and slaughtered “suspected terrorists”—often along with women and children who happened to live with them. Scahill visits one such family, who offer evidence that the relatives U.S. forces killed or abducted had no connection to Taliban or Al Qaeda: The family patriarch, who was gunned down at his doorstep along with three female relatives, was an Afghan police chief who’d worked alongside the Americans. Minutes earlier, the victim had been dancing in a living room crowded with clapping loved ones; we see family videos taken with a camera phone the night of the killings.

While digging to find out who would conduct such a mob-style hit on civilians, Scahill learned about JSOC and its missions, which the White House assigns to the unit directly. The information wasn’t easy to come by. As Scahill explains, before the bin Laden assassination lent JSOC mainstream acceptance, there was practically no information about its size, funding, methods, or scope of activities. It was just mentioned as a generic special force that started as a hostage rescue team in 1980. Scahill and other journalists uncovered the fact that, under Presidents G.W. Bush and Obama, JSOC has become an all-purpose assassination and abduction squad to rival thugs of the most ruthless Third World warlords.

Speaking of: Schahill hangs out with Somali general Idnha Adde (formerly a U.S. enemy) and warlord Mohamed Afrah Qanyare as they battle “foreign fighters” on behalf of our Global War on Terror. When Scahill presses Qanyare for details about his campaigns, the leader tells him to ask the Americans. “America knows war,” he says. “They are the war masters.”

In Yemen, Scahill talks with the father of the American citizen who succeeded bin Laden as America’s public enemy #1, Anwar al-Awlaki. This segment argues that al-Awlaki started out as a peaceful young cleric before America’s unprosecuted crimes against civilian populations radicalized him. A series of video clips show al-Awlaki transitioning from a peacemaker in full sympathy with the U.S just after 9/11 to a cheerleader for jihad against the West. For Scahill, the drone strike that killed al-Awlaki is a turning point to the darker side of the dark side. With the 2001 Authorization of Military Use of Force allowing presidents to select for elimination any American citizen suspected of terrorist ties, who’s next to step out of his front door into the path of a Hellfire missile? Al-Awlaki’s death might not move too many people who find al-Qaeda associates automatically fit for destruction, but what about his 16 year-old son, a nerdy, friendly suburban 16 year old from Denver with no terrorist ties? A CIA-devised attack killed him, too.

In these passages, “Dirty Wars” keeps it simple: We see al-Awlaki’s father watching home video of his grandson, a typical American kid having fun. The boy’s sister watches the video, too, her eyes brimming with loss. We’ve been here before. Popular documentaries like Michael Moore’s “Fahrenheit 9/11” did their best to demonstrate that foreign kids suffering or perishing because of disastrous U.S. policy are “just like our kids.” Given the incessant, almost automatic dismissal of such murders of children in this country—by pundits, Congress members, White House press secretaries, American generals, soldiers, and average Joes and Janes—it’s hard to see any meaningful difference between the folks who danced in the streets when the towers fell and Americans who find collateral damage offensive only when the collateral is American. Casual dehumanization of foreigners has become the norm everywhere. It’s as if 9/11 rolled back the world clock a century.

Scahill, Rowley and co-writer David Riker (creator of the classic neo-neorealist indie “La Ciudad”) do their part to attack this backwardness at the root. Clear and graphic images of the piles of dead children a U.S. drone strike left in a Yemeni field say so much more than (to cite a quietly outrageous moment early on) a general smugly, idiotically speculating that a pregnant Afghan woman our soldiers gunned down might have been a combatant. (“I’ve been shot at by women.”)

Filmmakers like James Longley (“Gaza Strip,” “Iraq in Fragments”) and “Restrepo” directors Sebastian Junger and the late Tim Hetherington came at similar material in a very different way, by embracing a kind of meditative docu-poem format. But there is too much reporting here for that kind of extended detour into war’s psychic landscape, and the movie knows that if it can’t give this mountain of facts some kind of shape, and keep the audience engaged throughout, its point will be lost. To that end, “Dirty Wars” tries to be a thriller, in much the same way the way “Fahrenheit 9/11” tried to be an outraged folksy comedy. It applies the tone and style of a fictional genre to a story of real people, real atrocities and real coverups. It plays like a hardboiled procedural. The movie treats Scahill as if he were George Clooney digging around for clues, piecing the puzzle together in a clockwork flow of images straight out of the pro-war works of Jerry Bruckheimer. It’s a strategy similar to the indie conspiracy thriller “Able Danger” in which a Brooklyn hipster-hacker learns that 9/11 was an inside job.

Unfortunately, Scahill is so respected and convincing that he doesn’t need such propping up, so the flashy directing and editing makes it feel as though “Dirty Wars” is trying too hard to sell things that might have sold themselves just fine without the hot box approach. The reporter’s story doesn’t just hold water, it proven solid enough to provoke mainstream media appearances and Congressional investigations. As a result, even though the tale is urgently important, one still comes away with the sense that something valuable has been lost in the telling. Filmmakers trying to counteract all the CIA and Pentagon-supported Hollywood propaganda out there must learn to trust straightforward, clear-eyed storytelling, rather than mimic Hollywood’s loud, hollow inducements. People see right through that crap.