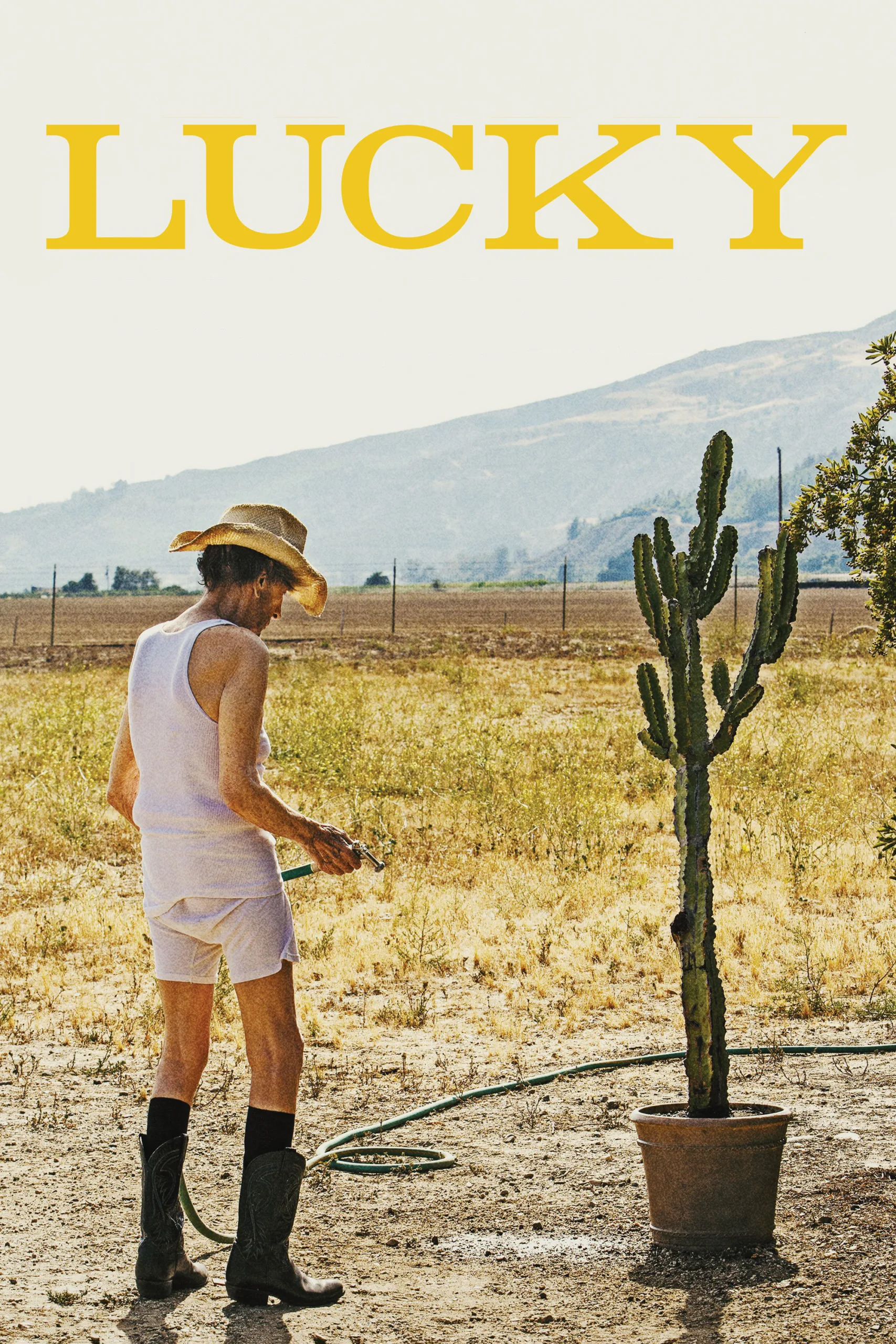

“Lucky” begins with a series of shots of the Arizona desert: broken-backed hills, cacti reaching for the sky. It locates a tortoise crawling. This is President Roosevelt, whose predicament we’ll learn about in due course. Then it settles on a human equivalent of that tortoise: the title character, Lucky, played by then-89-year old Harry Dean Stanton, who died mere weeks before this film’s release.

Over the course of the next 88 minutes, we spend almost every moment in the company of Lucky. Lucky is a long-retired World War II veteran. He has friends but is often brusque and impatient with them. He has a routine, and like many older people, it gives shape to his days.

He walks around town and stops in the local coffee shop, where he talks to the head cook (Barry Shabaka Henley) and a particular waitress, Loretta (Yvonne Huff), who takes an almost daughterly interest in his well being, to the point of stopping by Lucky’s tiny home to inquire about his health and share her stash. Lucky goes to his favorite bar and drinks and talks to the owner Elaine (Beth Grant) and her husband Paulie (James Darren, of TV’s “T.J. Hooker” and several “Gidget” films). They argue amongst themselves and with other patrons about philosophy, morality, religion, game shows. We see a lot of Lucky at home, often in his baggy underwear, doing yoga exercises and smoking cigarettes (he has a pack-a-day habit, has since he was a teenager).

“Lucky” is filled with frank talk about primal subjects. This is often framed as banter, or enclosed within routine events such as a random conversation in a restaurant (Tom Skerritt plays another World War II veteran; he’s too young for the part but you believe him anyway) or in a doctor’s office (Ed Begley, Jr. plays Lucky’s physician—what a treasure trove of actors!).

But the story’s deeper meanings reside in its images of Harry Dean Stanton moving at a tortoise’s pace through a series of sun-drenched, Western-styled panoramas (the soundtrack often playing a solo harmonica version of “Red River Valley” performed by Stanton), or making his way from the entrance of his favorite coffee shop or bar to his customary seat (when he sees someone else sitting there, it throws him for a loop).

This movie is about death, of course, and fear of death, and health, and loneliness. It’s about the choices not made and the roads not taken: Lucky has a lot of regrets, but you often have to deduce what they are, because he’s the kind of crabby old eccentric who’d rather debate than talk. (Other people talk more openly than he does, often as a means of trying to get him to open up and be vulnerable, which is not his style.) Much is made of Lucky’s atheism, which complicates his defiant attitude towards the inevitable approach of death.

“Friendship is essential to the soul,” Paulie tells him at the bar.

“It doesn’t exist,” Lucky replies, an edge in his voice.

“Friendship?” Paulie clarifies.

“The soul!” Lucky yells.

The movie is also about friendship, especially as emphasized in Lucky’s conversations with his buddy Howard, played by David Lynch as a dandy in a cream-colored suit, white fedora, and red ascot. Howard is distressed about the disappearance of Theodore Roosevelt, his beloved, ancient tortoise (call the animal a turtle at your peril). Lynch directed Stanton in many projects, including the recent “Twin Peaks: The Return,” which cast the actor as a weathered exemplar of decency: a trailer park manager who offers to give a jobless tenant a break on the rent so he won’t have to keep selling his blood, and who cradles a dying boy and watches his soul rise to heaven. There’s an extra-dramatic thrill to watching these two, who have known each other for at least thirty years, play old friends. Lynch holds his own: whether he’s as fine an actor as Stanton or just knows how to talk to him is a moot point. Love and respect light every moment.

Lucky is the kind of guy whose capacity to make new friends either went dormant or switched off. He’s as surprised as anybody when he finds himself opening up to younger people, including Loretta, who has issues of her own, and a young insurance agent played by Ron Livingston, whom Lucky initially despises but who opens up suddenly, almost desperately: a drowning man begging for rescue.

The movie was written by Logan Sparks and Drago Sumonja, and directed by longtime actor turned filmmaker John Carroll Lynch (of “Fargo,” “Zodiac” and so many more—he’s another Stanton in the making). I’ve seen a lot of movies that try to be “Lucky”—movies about eccentric people in a small town or neighborhood who hang out in bars and coffee shops and have conversations—but few that have this film’s elegant shape, its sense of when to hang back and listen and when to let the camera tell the story, and when to end a thought and move on to the next one.

It’s the humblest deep movie of recent years, a work in the same vein as American marginalia like “Stranger Than Paradise” and “Trees Lounge,” but with its own rhythm and color, its own emotional temperature, its own reasons for revealing and concealing things. There’s a long scene of Lucky smoking cigarettes at night and thinking. The soundtrack plays Johnny Cash’s “I See a Darkness,” one of many late-career classics in which the singer faced the certainty of his own death. The sandblasted terrain of Stanton’s face in this scene constitutes a movie within a movie, a life revealed in contemplation. It’s one of the most powerful things I’ve ever seen. I felt that way before Stanton left us. I feel it even more keenly now.