The title of Steve James’ new documentary “Abacus: Small Enough to Jail” is a play on a phrase that was popularized during the 2008 financial crisis: that certain banks were “too big to fail” and had to be rescued by the United States government to stave off total economic collapse. Among the more shameful legacies of that period is confirmation that if you’re an executive of a multi-billion dollar international financial institution, nothing you do, no matter how stupid or willfully criminal, will result in anything worse than a comparatively minor fine, and you might not even have to pay that.

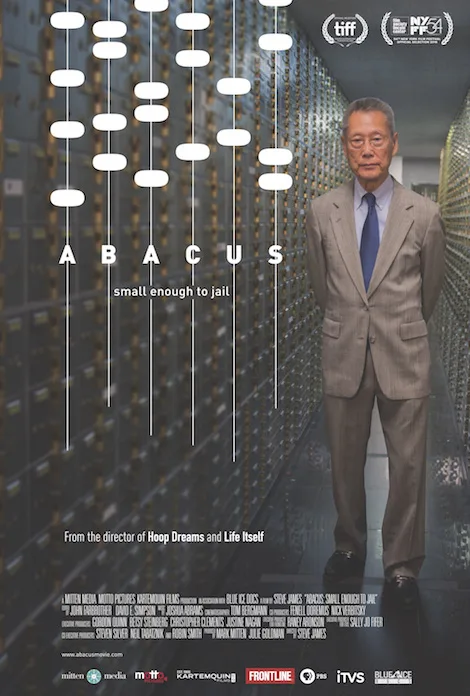

But if you’re a small, family-owned bank in Chinatown, well, it’s a different story. The titular bank is named for the Chinese calculator. It’s owned and run by the Sung family, Chinese-Americans who live in Greenwich, Connecticut and commute to Manhattan to oversee the flow of funds, the distribution of loans, the collection of payments and so forth. James, whose distinguished career includes “Hoop Dreams,” “At the Death House Door” and the recent Roger Ebert documentary “Life Itself,” has a knack for finding the universal within the specific, and often a much larger and more complex story nestled within a specific account of one event.

That’s the case here, too. The main object of interest is the 2015 trial of Abacus bank officials on charges of conspiracy, larceny and systemic fraud. But woven around that is a story of immigrants assimilating and obeying the laws of their home country over generations, only to be made an example by their adopted nation’s power structure for what seem, in James’ account, like specious or intellectually dishonest reasons.

As the film explains, no one in the Sung family—including bank co-founders and married couple Thomas and Hwei Lin Sung and their four daughters—was directly connected to the shenanigans in the loan department of their Chinatown bank. The offenses included embezzlement, bribery and larceny. Documentation proves that once the Sungs realized they were employing dishonest people, they fired them immediately and reported their offenses to authorities, even providing fat binders full of documents to the district attorney’s office to strengthen the case against the accused. James makes a compelling case that Manhattan district attorney Cyrus Vance, Jr. threw Abacus and the Sung family under the bus because he needed to prove he was tough on white collar crime, and knew he could scapegoat a Chinese family because they owned a small, independent bank in a community too small to affect his chances at re-election.

Government and media witnesses to the investigation and trail agree that they never saw anything like the treatment of Abacus bank employees by Vance’s office. They were handcuffed and paraded down public corridors in a group of fifteen, their wrists linked by handcuffs as if in a chain gang, and three of the people in that lineup were Chinese-Americans who technically shouldn’t even have been there because they had already been released on bail. (Rolling Stone columnist Matt Taibbi called the image “almost Stalinist.”) There is, by this film’s account, no compelling evidence that the Sungs were guilty of anything worse than failing to detect the actions of dishonest employees until they’d already caused a lot of damage. The case presented by the film is one of negligence or poor oversight, not active conspiracy to break laws.

But as gripping as the movie is as a legal thriller, it’s even more notable as a portrait of a community. James, whose crew spent many hours with the Sungs all over Chinatown and in Connecticut, has constructed a rich and revealing context for this tale, and it’s one that is rarely showcased in American cinema. This is a film filled with Chinese people engaged in an underdog story not unlike the one in “It's a Wonderful Life,” a film the Sungs adore and that inspired Thomas to enter the financial industry. We get a strong sense of a thriving community that defines itself in relation the mainstream of American culture and that is aspirational but never entirely comfortable or accepted. This is a precarious psychic state to exist in for successive generations, and it’s unusual to see it portrayed onscreen with such empathy and nuance.

More immediately fascinating, though, is the film’s depiction of an accomplished Asian-American family filled with strong-willed, educated professionals who obviously love and respect each other and have a great rapport. Some of the most striking scenes in “Abacus” are unrelated to the trial itself. They just show the Sungs sitting around a kitchen table or a table in a Chinese restaurant, talking about money, the law, the movies and each other. They talk over each other, interrupt each other, talk over each other. They crack jokes, tease, apologize and compliment one another. The physical fact of their existence onscreen is inspiring. So is the film’s impressive array of archival images, documentary film snippets and bits of TV news reports, showing Chinatown through the ages. There is history here. An entire world. And we finally get to see it. What happened to the Sungs seems horribly unfair, but this film is a silver lining. Everyone needs to see it.