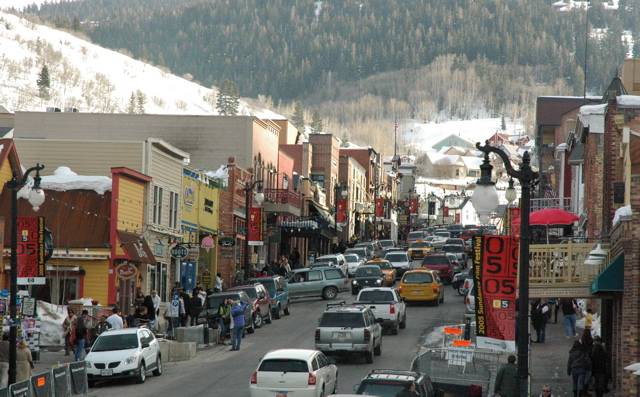

PARK CITY, Utah — I took a day off to cover the Oscars, and I’m nine films behind. That’s nine I’ve seen, not nine I’ve missed. They are so various and in many cases so good that the problem is to write about them without sounding like a crazed cinemaniac.

“Grizzly Man” is the best place to start. This new documentary by Werner Herzog is an astonishing portrait of Tim Treadwell, who like many of Herzog’s subjects is possessed of a serene ecstasy that forces him to go too far, try too much, risk his life in his search for the sublime.

You read about Treadwell in the papers, or maybe you saw him on “Letterman.” He’s the guy with the Viking haircut who spent 13 summers in Alaska living with grizzly bears. He spoke their language, he said, and knew their moods, and survived unarmed among them. But in the autumn of 2003 the communication broke down, and Treadwell and his girl friend were killed and eaten by a bear — a bear he didn’t much like.

Herzog, a great filmmaker, doesn’t simply tell this story but transcends it, engaging in a debate with the dead man over the nature of Nature. Treadwell thinks Nature is harmonious. Herzog says he thinks it is made of “chaos, hostility and murder.” When Treadwell looks into a bear’s eyes, he sees a friend. Herzog sees a wild animal, curious and possibly hungry.

Treadwell got a video camera in 1999, and left behind 80 hours of extraordinary footage taken in the wilderness. The footage includes shots taken hours before his death, at the place where his bones were found, and shots of the bear that would eat him. He comes across as an engaging, exuberantly childish man who talks to the animals as if they were children, and dramatizes his own mission and the constant danger he says (accurately) surrounds him. Herzog talks to his friends, former lovers and partners, to the pilot who dropped him off and found his remains, and the coroner who opened up the bear.

“Grizzly Man” is chaotic, hostile, deadly, harmonious, and brilliant.

I also greatly admired “Nine Lives,” by Rodrigo Garcia, which has a large cast including many famous names, and uses them in a series of nine vignettes, each one filmed in a single shot of 10 to 12 minutes. Some of the segments have the impact of great short stories. For example, a scene in which Robin Wright Penn plays a pregnant woman who is in the supermarket when she meets a former lover, also now married. It becomes clear to them that their old attraction is still powerful. In another lovely scene, Aidan Quinn and Sissy Spacek meet in a motel for illicit love, but the arrest of a woman in another room changes the dynamic. Glenn Close stars in a bittersweet closing segment in a cemetery. The film’s mood is elegiac but hopeful, as needy people uncertainly reach out to one another.

Rebecca Miller’s “The Ballad of Jack and Rose” stars her husband, Daniel Day-Lewis, as the last survivor of a 1960s hippie commune. He lives on in his wind-powered island house with his teenage daughter (Camilla Belle), in a relationship too close to be healthy. After a heart attack, concerned about the future, he promises marriage to his mainland girl friend (Catherine Keener), and she arrives with her two sons. Miller, who also wrote, develops the story not as a standard relationship crisis but as a series of tenderly observed and sharply emotional surprises.

Steve Buscemi’s “Lonesome Jim” is a little masterpiece of mood, starring Casey Affleck as an Indiana boy who fails to make it in New York and returns home to a relentlessly cheerful mother (Mary Kay Place), a distant father (Seymour Cassel) and a brother (Kevin Corrigan) who soon enough is in the hospital. There Affleck meets a nurse (Liv Tyler), and they begin a relationship filled with apprehension, caution and the frightening possibility of love. It’s not what happens so much as how it feels, and sometimes it’s funnier than I make it sound.

Michael Hoffman’s “Game 6” is a written picture, by which I mean that the dialogue must be attended to as in a stage play. It’s the first and only screenplay by the novelist Don DeLillo, with Michael Keaton as a successful playwright, Griffin Dunne as a writer who is falling to pieces, and Robert Downey Jr. as a critic of great eccentricity. Because the principal characters are writers, they talk like writers, with specific and evocative word choices. Mostly what they talk about is the collapse of the Boston Red Sox in 1986. Game 6 of that famous World Series unfolds during the movie, as the men find a metaphysical connection between themselves and their team. DeLillo’s dialogue allows for a complexity and richness of speech that is refreshing compared to the subject-verb-object recitation in many movies.

There are other good films I will write about, but my space comes to a close, and I must not neglect Stephen Chow’s “Kung Fu Hustle,” which is — what? Imagine a film in which Jackie Chan and Buster Keaton meet Quentin Tarantino and Bugs Bunny. Yes. That describes it nicely.

Oh, and I met a man named Dave Gebroe here, who says I must see his film “Zombie Honeymoon,” which he describes as his response to my call for a truly romantic horror film. I cannot quite remember issuing that call, but no doubt he is right, and certainly there is a tragic lack of such films.