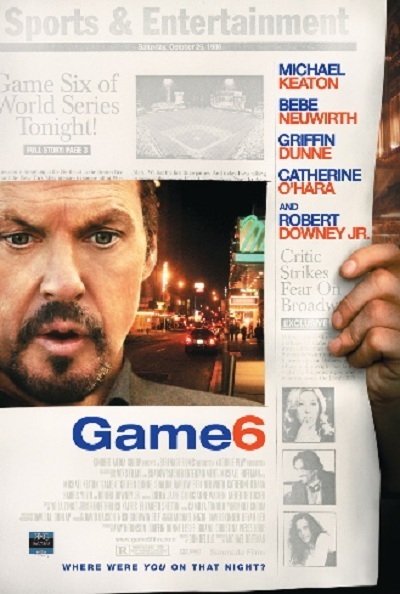

Michael Keaton is a talker. His strength as an actor is in roles that position him on the scale between literate and glib; even in the wonderful lost film “Touch and Go” (1986), where he played a pro hockey player, he spoke like one who had a novel in him. In “Game 6,” he plays a playwright and talks like one, taking pleasure in choosing specific words to evoke exactly what he means. He is also a Boston Red Sox fan, and when the opening night of his new play coincides with the sixth game in the 1986 World Series, he has a lot to talk about: “I’ve been carrying this franchise on my back since I was 6 years old.”

The original screenplay is by the novelist Don DeLillo, and it involves subjects (or obsessions?) he used in his novels Underworld (1997) and Cosmopolis (2003). From the first comes expertise on baseball, pitched somewhere between torch songs and Greek tragedy. From the second comes the Manhattan gridlock and the undercurrent of danger and violence in the streets. The playwright, named Nicky Rogan, abandons a cab after an exploding steam pipe sprays asbestos into the air, and retreats into a bar where he finds an old friend and fellow playwright, Elliot Litvak (Griffin Dunne). Because it is Nicky’s opening night, they talk about a critic they both hate; Elliot believes this man destroyed his life, and indeed seems to be entering madness.

This is DeLillo’s first produced screenplay, but he has written for the stage, and perhaps his portrait of Steven Schwimmer (Robert Downey Jr.), the detested critic, is drawn from life. I can think of a candidate. Schwimmer has written such lethal reviews of plays that he lives in hiding, is forced to attend opening nights in disguise, and goes to the theater fully armed. Elliott speaks of him in wonder: “I opened a one-act play at 4 a.m. in the Fulton Fish Market. In the rain. For an audience of fish-handlers. Schwimmer was there.”

In addition to his fears about opening night and his premonition that the Red Sox will once again destroy his dreams, Nicky is facing personal problems. While one of his cabs was stuck in traffic, he saw his daughter Laurel (Ari Graynor) in another one; visits between cars stuck in traffic are also an Underworld theme. She informs him her mother is divorcing him: “She says daddy’s demons are so intense, he doesn’t even know when he’s lying.” There is consolation in an affair he’s having with an investor in his play (Bebe Neuwirth), but not much.

Writers find strange connections in their days and lives; they generate wormholes that connect people. How else to explain that one of the taxi drivers “used to be head of neurosurgery in the USSR,” and the star of his new play (Harris Yulin) can’t remember his dialogue because he has, the director says, “a parasite living in his brain.” Yulin’s character has a painful rehearsal where he fails again and again to remember the line that has just been repeated to him.

This material could be pitched at various levels. You can imagine it being incorporated into a sequel to “The Producers,” or being transformed into quasi-O’Neill. Keaton, DeLillo and director Michael Hoffman make it into a celebration of spoken language; we’re reminded that Hoffman directed “Restoration” (1995) and the 1999 “Midsummer Night’s Dream.” After the Sundance opening of “Game 6,” I wrote: “DeLillo’s dialogue allows for a complexity and richness of speech that is refreshing compared to the subject-verb-object recitation in many movies.” Such dialogue requires an actor who sounds like he understands what he is saying, and Keaton goes one better and convinces us he is generating it. Life for him is a play, he is the actor, his speech is the dialogue, and he deepens and dramatizes his experience by the way he talks about it. Certainly what he says about the Red Sox has a weary grandeur.

Robert Downey Jr., whose troubles of a few years ago were well documented, has come back with a vengeance; his career is ascendent, and since “Game 6” was finished in 2005, he has made 10 other movies, ranging from “Good Night, and Good Luck” to “The Shaggy Dog,” and that’s some range. Here he makes the critic Schwimmer into a study in affectation, a little Buddhist, a little loony, a little paranoid, a little fearless. Griffin Dunne, who also produced the movie with his filmmaking partner Amy Robinson, plays the disintegrating playwright Elliot as a man halfway between barroom philosopher and dumpster-diver. And for Nicky, everything comes down to which is more important: Success for his play, or the Red Sox winning Game 6? Talk about backing yourself into a lose-lose situation.