The breadth of subject matter in the U.S. Dramatic Competition of Sundance 2019 was on full display over the first 24 or so hours of this year’s film festival in drastically different works from three fresh directors of completely different backgrounds.

The best of the three is Lulu Wang’s excellent “The Farewell,” a phenomenal dramatic moment for the breakout star of “Ocean’s 8” and “Crazy Rich Asians,” Awkwafina. Wang has written a deeply personal film that claims to be “Based on an Actual Lie,” and she’s found precisely the right star to maintain the delicate balance of this story – one that easily could have become sentimental and manipulative but resonates with truth from first scene to last. This will go down as one of the best performances of Sundance 2019, a genuine, heartfelt acting turn that proves that Awkwafina has a range that even her most diehard fans may not have suspected. She never once feels mannered or forced, completely disappearing into her likable, heartbreaking character.

She plays Billi, a struggling writer in New York, whose extended family is still in China. Her father (the wonderful Tzi Ma) left China a quarter-century ago for the States, and his brother raised a family in Japan, but the matriarch of the clan, Billi’s grandmother (Zhao Shuzhen), is back in China. From the very first scene between Billi and her ‘Nai Nai,’ as they have what appears to be a regular phone conversation, one can sense the support and love between the two, even though they’re hundreds of miles apart. So it’s believable that Billi is shattered when she learns that Nai Nai has lung cancer—the doctors are giving her three months.

In what is apparently culturally commonplace, Billi’s family makes a decision that some people might find abhorrent—they don’t tell Nai Nai that she’s dying. As Billi’s uncle Haibin (Jiang Yongbo) says, it’s the family’s emotional burden to bear. And so the family stages a wedding between Billi’s cousin Hao Hao (Chen Han) and his new girlfriend Aiko (Aoi Mizuhara) so that the family can all go to China to say goodbye to the family matriarch…without her knowing they’re saying goodbye.

“The Farewell” has some beautiful, truthful things to say about how love persists across the oceans. We often move away and leave our family, but we are more intrinsically tied to them than we ever will be to anyone else. And watching Billi, at a formative point in her life, comprehend the influence her grandmother has had on her while fighting her natural instinct to literally say goodbye makes for powerful filmmaking. As someone who recently said goodbye to a grandparent, the things this film says about how love transcends language and location struck me as powerfully true. It will likely make you wish you spent more time with your grandparents, but it will also reaffirm how important your connection to them was even though you didn’t.

A far different family connection is captured in Alma Har’el’s “Honey Boy,” a film that represents a cinematic act of courage for its writer and co-star Shia LaBeouf, who delivered the director a screenplay that’s based on his own upbringing as a child star under the thumb of an abusive father…played in the film by LaBeouf. “Honey Boy” opens with a riveting montage of a young actor in 2005 named Otis (Lucas Hedges), who first appears on the set of an action movie that is clearly a stand-in for “Transformers.” The montage ends with Otis being told that he has symptoms of PTSD. He doesn’t understand how that’s possible. What’s his trauma? It’s his upbringing. And it’s Shia’s upbringing. “Honey Boy” is the cinematic exorcism needed to deal with a major actor’s PTSD. On that level, it’s riveting drama, always existing as a personal, meta piece for a man openly and artistically dealing with his past while also being a study of child stardom, addiction, and abuse.

The increasingly impressive Noah Jupe plays young Otis, stuck in a sleazy motel with his dad James, who he pays to be his assistant. Otis is a child star of a certain level, not big enough to live the L.A. high life, but big enough to keep him and his dad alive. James is a former rodeo clown, former alcoholic, former convict, and former sex offender. He’s that classic male type who finds a way to blame everyone else for his failures. He’s selfish. His problems and needs are more important than his son’s, and we know that from minute one when he’s too distracted by a pretty woman to take care of Otis. Much of “Honey Boy” plays out like a tense two-hander with Otis and James in their tiny motel room, and the audience waiting for an outburst.

There are parts of “Honey Boy” that feel repetitively over-directed and then other parts that feel under-directed—moments I wanted to live in longer, to have the director let them breathe more. It has a herky-jerky rhythm at times, although that could be to reflect the way that traumatic memories often return to us. And yet my problems with “Honey Boy” are vastly overshadowed by the courage it took to even make this movie. Labeouf has become a really fascinating actor in challenging work like “American Honey,” “Nymphomaniac,” and even “Borg v. McEnroe,” and I’ve found myself rooting for that trajectory to continue. Hopefully, just making “Honey Boy” allows him the closure he needed.

As much as I went into “Native Son” excited for a modern telling of Richard Wright’s 1940 novel, with a pair of fascinating young actors, that excitement dissipated as the movie continued. Visual artist Rashid Johnson’s choice for a directorial debut is an undeniably ambitious interpretation of a challenging novel to turn into a film with a incredibly talented cast that includes “Moonlight” break-out Ashton Sanders and “If Beale Street Could Talk” break-out Kiki Layne. The casting wasn’t the only thing here inspired by the work of Barry Jenkins. And one can easily appreciate the ambition embedded in an attempt to illuminate how the themes of Wright’s work resonate eight decades later. But there were decisions made in this production – both in how the work has been updated and how it was not – that drain “Native Son” of the momentum it really needs.

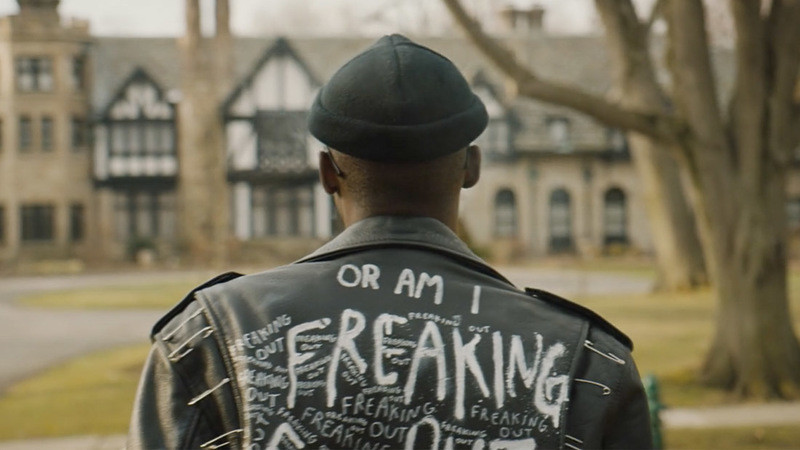

The story is certainly still a fascinating one. Bigger “Big” Thomas (Sanders) lives in Chicago with his mom and two siblings. He’s a fascinating dichotomy in that he’s the kind of guy who seems like he wants to fade into the background – just hanging out with his girlfriend Bessie (Layne, who should be a household name any day now and is the best thing here). He feeds local kids, watches movies, refuses hard drugs, and stays out of trouble, refusing his buddy’s pleas to help rob a store. But he’s also got a fashion style that screams for attention with green hair, black fingernails, and a jacket that almost looks spray-painted. He wants to take unpredictable routes through life, and his favorite punk bands, including Death and Bad Brains, both mirror and influence his personality.

Then he gets a very unpredictable job, as the driver for a wealthy Chicago power player named Will Dalton (Bill Camp), a power player in the Windy City with an Evanston mansion and a blind wife (Elizabeth Marvel). There’s a fascinating, uneasy tension in Dalton house, which has no security cameras and still uses a coal furnace. And the Dalton daughter, Mary (Margaret Qualley) is drawn to Bigger in part as another notch in her list of multicultural experiences. The first time they meet, she asks him if he’s “outraged” and wants to go to a soul food restaurant on the South Side. He represents a world she’s passionate about through protest but knows little about on a practical level.

The second half of “Native Son” is as tricky as storytelling gets, and Johnson can’t quite get a handle on it, including the “big scene,” which is poorly handled tonally. And then he makes major changes to the events that unfold after that, which result in a clipped ending that lacks impact. The mannered storytelling and direction of the performances start to push audiences away right when the movie needs to pull them in, and he makes one major adaptation decision that simply doesn’t work. Most of all, right when it needs urgency, it’s a movie that mistakes pregnant pauses and whispered lines for “deep meaning,” and even though the clearly-talented Sanders is totally committed, Johnson directs his leading man into a performance that feels showy right when it needs to be heartfelt, angry, and direct.

There are still powerful moments and interesting performances, so it’s far from a complete miss, but most of what works about “Native Son” is on the surface. Every time you try to dig below to find the emotion that drives it, you come up empty. I wanted “Native Son” to leave audiences short of breath, rolling its themes around in their minds. The story of Bigger Thomas needs rage and heat, but this version’s as cold as a Chicago winter.