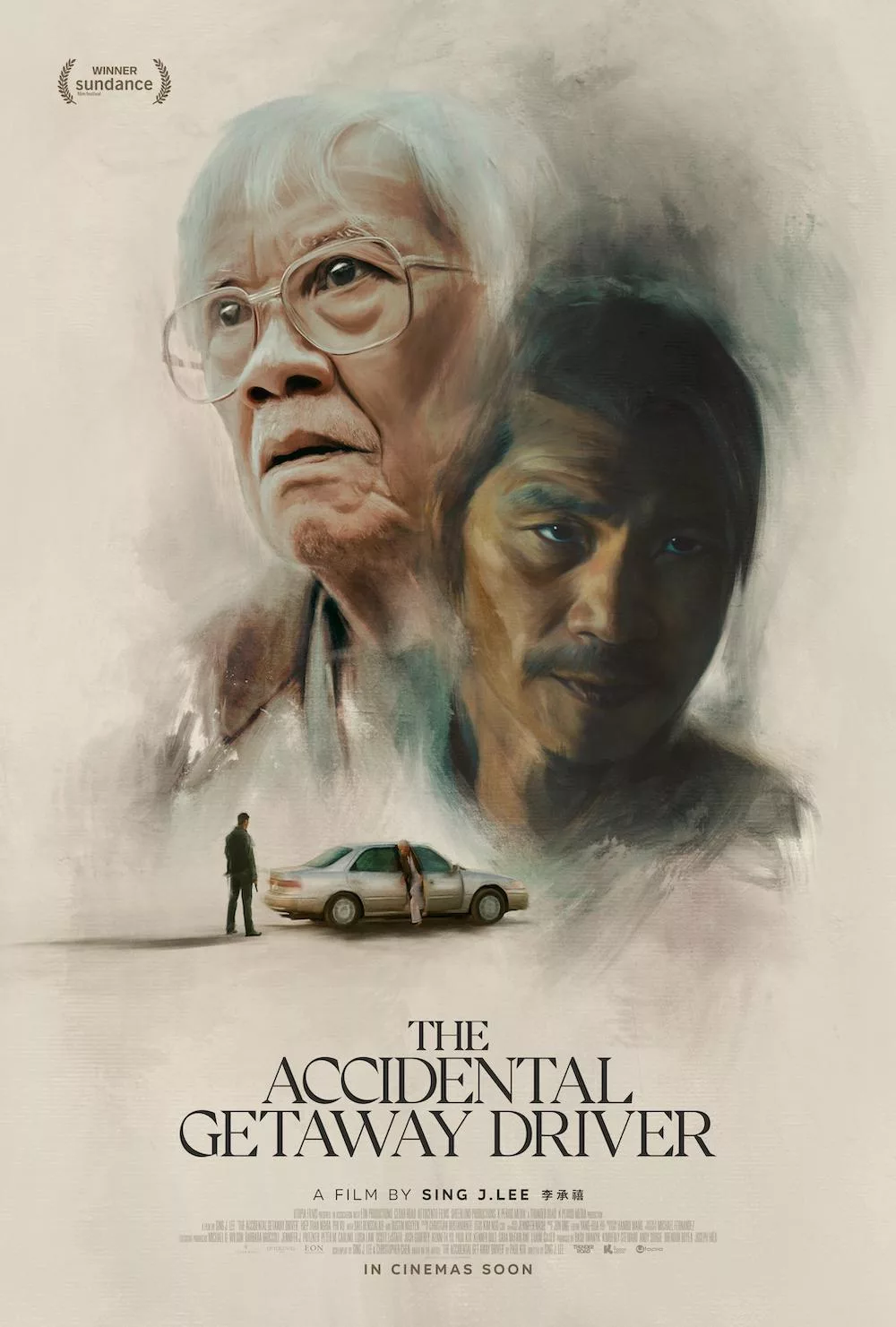

Based on the true story of a Vietnamese-American taxi driver who was briefly held hostage by three escaped convicts in Orange County, California, “The Accidental Getaway Driver” is hugely influenced by the crime thrillers of Michael Mann—”Collateral” and “Thief” especially—with crystalline widescreen nighttime photography and off-centered closeups of faces lost in thought.

But it’s much smaller and quieter than anything the master has made: essentially a stage play on wheels, with a long detour into a motel room. The elderly and soft-spoken main character is the cabdriver Long Ma (Vietnamese actor Hiep Tran Nghia, who didn’t start acting until he was 50!). He used to be a colonel back during the war years but this is not the kind of “badass old guy” movie where the hero is underestimated because of ageism but proves quite capable of climbing rain gutters, dropping through skylights and slitting throats. This is a psychological drama about the missed opportunities, painful losses, and mortifying mistakes that people carry around with them throughout their days, and that weigh on them even when guns aren’t pointed at their faces.

Like poor Dante in “Clerks,” Long Ma wasn’t even supposed to be working that day. He got a call on his cell phone while shopping late at night and had to be convinced by the dispatcher to accept the job and pick up the rider. Turns out there are three riders: the possibly unstable hardass Aden Salhi (Dali Benssalah), the likable and insinuating Tay Du’o’ng (Dustin Nguyen), and baby-faced Eddie Ly (Phi Vu). They climb into Long Ma’s rundown car to go…well, do they even know what they’re doing? The details are understandably sketchy. But Long Ma figures out pretty quickly that he’s a hostage and isn’t sure what to do about that.

There’s a particular sort of Western that “The Accidental Getaway Driver” might remind you of, if you’re into that movie genre: the wilderness adventure in which criminals take innocent people hostage while going from Point A to Point B, and since the hostages cannot liberate themselves through force of numbers or firepower, they instead try to get into their captors’ heads and underneath their skins and manipulate them into liking them or realizing how much they dislike each other (sowing discord). Long Ma isn’t purposeful and calculating in that way. But the individual conversations between him and his passengers, which initially stall out because of machismo and codes of silence, do serve much the same function, establishing genuine connections between the driver and the passengers that remind them of their shared humanity.

Some of the best moments in the movie are closeups of one criminal or the other as he looks at or listens to or simply contemplates Long Ma, and you see in their faces that they are suppressing the urge to think about this old man as something other than, well, collateral. In his feature debut, director Sing J. Lee (who also cowrote the script, with Christopher Chen) proves he has a steady hand with visuals and performances. This is clearly a filmmaker who knows what he likes and wants, and knows how to connect with his collaborators (among them: cinematographer Michael Fernandez, a wizard of negative space). This is one of those rare productions that conjures a vibe that feels big even though the production was small.

The result is thoughtful, honorable and sometimes moving, though there may not actually be enough gas in this movie’s tank, narratively speaking, to justify even its comparatively brief running time. It takes too long to get into gear. And some of the more lingering pauses or the formally rigorous compositions, while gallery-ready in terms of blocking and lighting, get in the way of the performances without meaning to (like a conversation in a hotel room in the dark, where you can only see the rectangles of the windows to the outside, not the room itself). This is an ambitious first film that is impressive in its ability to create an entire world with its own atmosphere and drop the viewer right into it. But in the end, it feels a bit more like a promise or a notion than a freestanding object that you’ll want to revisit to dig out all the subtleties you missed the first time.

Its greatest asset is its performances, which operate in strikingly different registers (some more subtle or ‘naturalistic’ and others more heightened) yet somehow work together to further the film’s story and themes. Hiep Tran Nghia is the standout, existing onscreen rather than performing in some obvious sense. The biggest difference between stage acting and film acting is that the latter is an act of in-the-moment collaboration with artists who are actively adjusting to each other’s creativity; as one veteran actor explained it to me, sometimes the best kind of movie performance is one where the actor understands what everyone else is doing and opens up emotionally and intellectually to become sort of a human canvas that the other artists can imprint themselves on. That’s the kind of work he’s doing in “The Accidental Getaway Driver.” In the spirit of the title, I don’t think he intended to steal the movie, but that’s what happens. I like to think he just tucked it into his back pocket and forgot about it.