“Native Son” dares us to look at a stupid and unnecessary murder through the eyes of the person who commits it, and to sympathize with the killer – to understand how he could have done it.

The story could have been told in other ways, but this is the way Richard Wright told it in his great 1940 novel, and the movie understands that the story really is about the killer’s point of view. It is not the story of a crime, not a docudrama, not a sociological essay; it is the story of how someone can do a dreadful thing, and not be completely responsible for it.

The movie tells the story of Bigger Thomas, a young black man growing up in Chicago during the 1930s. He lives in poverty, in a rat-infested tenement, and the film opens like the novel, with Bigger trying to kill a rat with a skillet. But this will be his big day; a rich, white, liberal family in Hyde Park wants him to come to work for them, and once he’s in the kitchen of their mansion, the maid tells him how good they are to “your people.” The family has a daughter, spoiled and willful, and she has a boyfriend who supports left-wing causes. Bigger is assigned to chauffeur the girl to her classes, but she orders him instead to pick up her boyfriend, and then the two of them try to make a friend out of Bigger. They want to show how liberal they are. They get him to take them to a black restaurant, and then they listen to jazz and get drunk, and the chain of events ends very late at night with Bigger carrying the drunken girl upstairs to her bedroom.

The next scene is the crucial one. The girl’s blind mother hears something and comes to investigate. Bigger is paralyzed by the fear that he will be discovered in the white girl’s bedroom, and when she starts to whimper, he covers her mouth with a pillow, and accidentally suffocates her.

The rest of the movie is a horror story, as Bigger disposes of the body and then helplessly waits for his crime to be discovered.

The point of the movie is not the investigation of a crime, however. It is the investigation of Bigger’s state of mind. How could he have done such a dumb thing? Through fear, the movie argues – and also through rage, for he is angry at the girl for having placed him in an impossible position.

One of the movie’s key scenes has the daughter and her boyfriend insisting that Bigger ride in the front seat with them, while the boyfriend drives the family limousine. They see this as a demonstration of how liberal they are. He sees it as unbearably condescending, and a threat to the job he was so recently so happy to have. Bigger is not articulate, is not able to explain how he feels, and so he gets cornered by his emotions and by circumstances. He kills, and yet he is not a murderer.

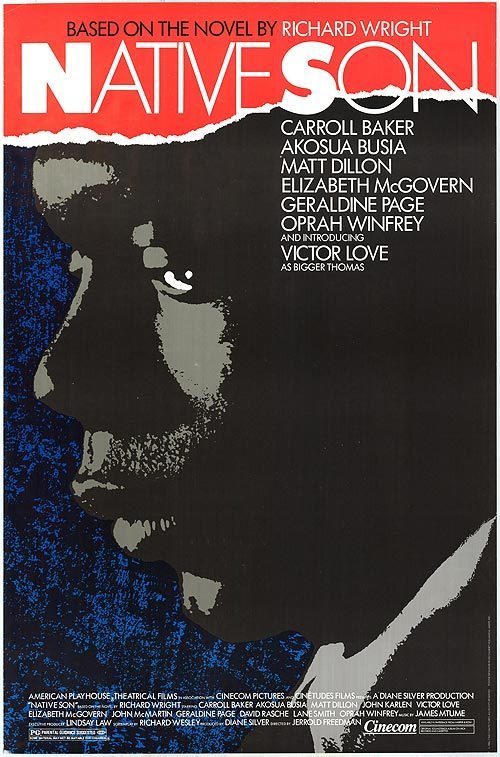

This is not an easy role to play, but a newcomer named Victor Love does a powerful job of it, and he’s equal to the strong closing scene in which he’s at last able to explain how he feels. Love is surrounded by a big-name cast: Elizabeth McGovern as the daughter, Matt Dillon as her boyfriend, Oprah Winfrey as Bigger’s mother, Carroll Baker as the dead girl’s mother and Geraldine Page as the maid. I am not sure that all the familiar faces help the story, although Winfrey and Baker, the two mothers, have a powerful scene together near the end, and Dillon is surprisingly convincing as the young radical.

“Native Son” is told in a deliberately unadorned style – perhaps because it was made on a limited budget – and each scene has to carry its weight. Many of the novel’s plot details have been left out, and although that diminishes some of Wright’s richness, it makes the central story all the more stark. In an afterword to the 1961 edition of the novel, Richard Sullivan wrote, “seeing the truth can be almost unbearable,” and in that sense he described “Native Son” as unbearable.

So it was, so it remains.