Founded in 1963, the New York Film Festival predated both

the Sundance and Toronto festivals, which eventually loomed much larger in

terms of size, media attention and industry influence (both serve as sales

markets). New York’s main claim to fame was as a tastemaker and gatekeeper: it

very selectively imported the most acclaimed films from abroad as well as

introducing important new voices in American filmmaking.

Under the 25-year leadership of the festival’s first

director, Richard Roud, the French definition of auteur cinema ruled, and the

consequent influence of the Cannes Film Festival made for programming heavy on

European films. In the next quarter-century, Roud’s successor, Richard Peña

broadened the festival’s scope in various ways, offering more documentaries and

American independents as well as showcasing auteurs from cinemas as diverse as

China, Taiwan, Iran, Egypt and Burkino Faso.

Even before Kent Jones took over from Peña four year ago,

the Film Society of Lincoln Center, which sponsors the festival, had been

undergoing various changes, some of which were reflected in a continually

expanding range of festival offerings: These now include “Spotlight on

Documentary” (a section I consider the most important addition of recent years)

and “Convergence” (about VR and various form of “immersive” storytelling);

revivals, retrospectives and restorations; filmmaker talks, salutes to actors,

etc.

The festival’s Main Slate, though, remains its chief calling

card, and rightly so: it aims to gather best of world cinema into a program of

only two to three dozen films (this year’s edition includes 25 features and

five programs of shorts). In recent years, one notable departure from the

festival’s traditional emphases entailed opening the doors to major-studio

movies, which led to Opening-Night slots for the likes of Paul Greengrass’

“Captain Phillips,” David Fincher’s “Gone Girl” and Robert Zemeckis’ “The

Walk.”

Whether such inclusions were intended to boost the

festival’s media or industry profiles or attract a broader base of donors—all

very understandable objectives—this year’s edition reverses the trend very

decisively. Its sole big-ticket item, Ang Lee’s “Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime

Walk,” comes from a great director with a NYFF history and is a special

presentation near the festival’s end. The Opening Night slot, meanwhile, will

be occupied by “The 13th,” Ava Duvernay’s documentary about the

mass-incarceration of African-American men. While the film wasn’t available in

time to be previewed for this article, I’m ready to lead the cheers for the

festival including a documentary as its Opening Night offering (first time

ever), especially one by such an estimable filmmaker.

I’ve been covering the NYFF for more than half of its

history, and perhaps the highest compliment I can pay its programmers is to

note that more often than not, as many as half the films on my annual 10-best

list appeared in the festival’s Main Slate. Granted, there are always reasons

to quibble: trendy or inconsequential films that are inexplicably included, and

anticipated titles that aren’t (this year my list of most regretted no-shows is

led by Ashgar Farhadi’s “The Salesman” and Damien Chazelle’s “La La Land”; both

directors are NYFF veterans). Yet it’s also been my experience that the films

that really define the festival’s special flavor every year are not just the

laureates from Cannes and other festivals but some of its less obvious, more idiosyncratic

offerings.

This year, the latter category is led by “Son of Joseph,” the latest by the New

York-born, Paris-based director Eugène Green. In recent years, my greatest debt

to the NYFF might have been the discovery of Green’s sublime “La Sapienza” (his

first film distributed in the U.S. and number one on my ten-best list of last

year) at the 2014 festival. Having now seen much of Green’s earlier work, I

count myself lucky to have encountered “La Sapienza” first, since its strikes

me as his one unqualified masterpiece and thus the film that provides the best

introduction to a body of work that is decidedly eccentric.

An American who went to France and helped revive its

tradition of Baroque theater before turning to filmmaking, Green is an anti-modernist

who wages war against pretty much everything that contemporary French

intellectual culture represents. Like the Dardennes brothers (who co-produced

“Son of Joseph” and whose exquisite “The Unknown Girl” is also in this year’s

festival) he owes obvious debts to the cinema of Robert Bresson in both his

essentially religious outlook and his pared-down visual style.

Like many of his films, “Son of Joseph” is rife with

Biblical references. Given Green’s Christian orientation, it’s no surprise that

the Joseph evoked here is he of the New Testament not the Old. The film’s

protagonist is a Parisian boy whose pervasive unhappiness seems to stem in

large part from the refusal of his mother (named, of course, Marie) to reveal

the identity of his father. In his probings, the teen discovers evidence that

his dad is a celebrated literary publisher (a wonderfully droll turn by Mathieu

Amalric) who’s as big a creep as he is a cultural icon. While pursuing him, the

boy also encounters and develops a friendship with the publisher’s brother

(Green regular Fabrizio Rongione), a kindly man who wants to return to his

family’s farm in Normandy.

In “La Sapienza,” the characters left the dry

intellectualism of Paris for Italy’s warmth, verdant landscapes and Baroque architectural

masterpieces; the film’s story describes a personal and philosophical journey

toward wisdom and healing. “Son of Joseph” is much different in large part

because it mostly remains planted in Paris, where its religious symbolism vies

against Green’s broad satiric swipes at the city’s literary scene. Some of this

is obviously intended as comedy, but other parts are less clearly jocular in

their intent, though many people in the press screening I attended laughed like

they were in a Mel Brooks movie. While Green certainly has his whimsical side,

I would say that the reactions his latest provokes mark it a mixed success by a

very unusual artist.

An expatriate from a different hemisphere, Alison Maclean

first visited the NYFF with “Kitchen Sink,” a 1989 short made in her native New

Zealand. Resident in New York since 1992, she returned to her homeland to make

the sharp, keenly observed feature “The

Rehearsal,” which follows a group of aspiring actors through their first

year of drama school.

Adapted from a novel by Eleanor Catton, the film inevitably

provokes the term “multi-layered” in part because we are always watching actors

playing actors learning about acting. But Maclean never makes this an exercise

in cerebral self-consciousness. With great subtlety and incisiveness, she

concentrates on drawing very detailed, believable characters and then follows

the process they undergo in gradually immersing themselves in a discipline

that’s at once seductive and demanding, vainglorious and ego-crushing.

Her main character, Stanley (charismatic Kiwi teen star

James Rolleston), is a country boy who, despite his good looks, approaches his

new life with the tentativeness of someone who lacks the confidence his urban

classmates have come by naturally. He meets his match in the domineering

personality of his main teacher (a strong performance by Kerry Fox). She sees

her role and breaking her students down before she can build them up again, and

at first Stanley seems like he just might not survive the ordeal.

The film, though, ably chronicles the personal

transformations and growth that students must undergo to discover the powers

their instructors see in the best of them. At the same time, they all have

lives outside the classroom, and “The Rehearsal” is very good at interweaving

the ups and downs of first-year-at-college, the roommate snarls, newfound

romances and hedonistic detours, even the unexpected tragedy. All in all, with

its sure sense of narrative and Maclean’s cool, restrained style, it’s a film

that makes good on the promise of her first two features, “Crush” and “Jesus’

Son.”

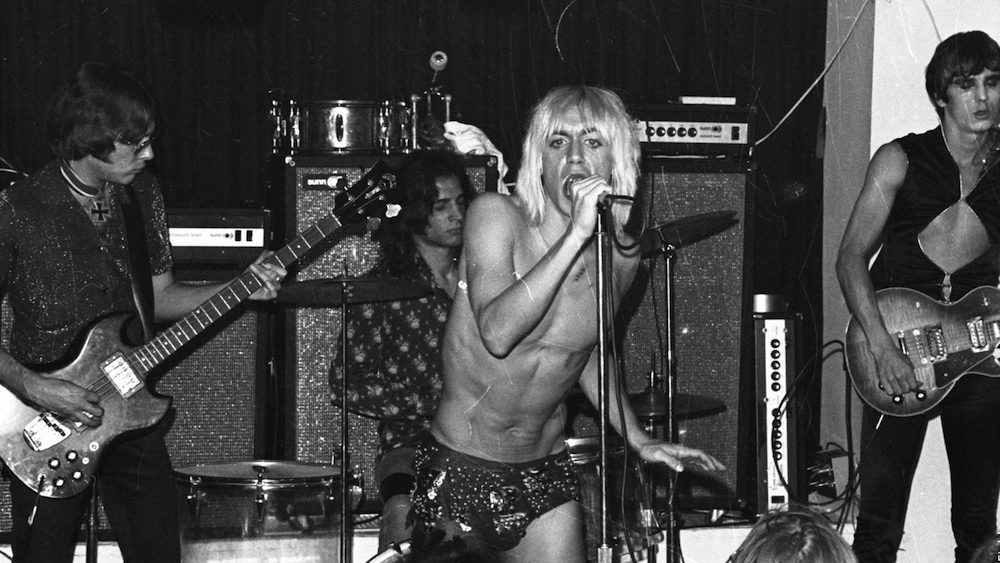

The festival dependably presents films about New York

cultural icons that are sometimes made by filmmakers who qualify as the same.

This year’s example, “Gimme Danger”

by Jim Jarmusch, opens with a gaunt, lank-haired guy sitting down in front of

the camera and being identified: “Jim Osterberg.” The name, of course, is the

real-life moniker of the protean performer the world knows as Iggy Pop,

erstwhile lead vocalist of the Stooges.

With Iggy eloquently narrating, Jarmusch initially throws

viewers a curveball in his documentary about the band by beginning the

chronicle in 1973, when they were at a low point, seemingly already washed up.

But soon enough the filmmaker doubles back and gives us the story

chronologically, starting with the Ann Arbor-based Stooges being discovered by

influential Elektra Records PR man Danny Fields. (This part of the story is

also recounted in Brendan Toller’s excellent doc about Fields, “Danny Says,” which

opens this week.)

Their signing with Elektra led to the wide-eyed Midwestern

boys being introduced to the fleshpots of the two coasts. In New York, Iggy

works with John Cale, begins a romance with Nico (who has recently broken off

with Lou Reed) and meets David Bowie, who would have a huge influence on his

subsequent career. In L.A., he encounters Andy Warhol and takes to wearing dog

collars. The Stooges’ first two albums, which were recorded in these separate

sojourns, would later be regarded as classics, but they didn’t set the world on

fire at a time when hippiedom and pot-flavored acoustic rock still ruled.

Elektra dropped them after the second disc, which sent the band into the usual

rock-star spiral of drugs, drink, fights, personnel changes and eventual

dissolution.

Commendably, neither Jarmusch nor Iggy ever uses the

hackneyed phrase “ahead of their time,” but the Stooges surely were—perhaps

more so than any American rock act apart from the Velvet Underground. The raw,

aggressive sonic assaults they unleashed on an unsuspecting public in 1970

influenced the Ramones in America, the Sex Pistols and the Clash in the U.K.,

as well as perhaps half the bands who would dominate the college radio airwaves

and U.S. club scene a decade later.

Though Iggy, whose Greek-god physique remains pristine after

nearly a half-century, disavows all labels including “punk,” his fearless stage

dives and utter disregard of injuries (which were manifold) set the parameters

for many future mosh pits and lead-singer derring do. He is still an amazing

performer, as well as a thoughtful and articulate teller of his and the

Stooges’ tale (the film also includes interviews with other surviving band

members). With a style that’s more straightforward and less quirky than one might

expect from Jarmusch, “Gimme Danger” provides an expert and engrossing overview

of one of America’s seminal rock acts.

Cream of the Crop

As noted above, the NYFF dependably provides a first look at

films that end up on my annual ten-best lists. Of the titles screened so far for

the press, four seem likely candidates for such honors, whether they go into

general release this year or next. I offer them here for festival-goers looking

for the best of this year’s Main Slate. All have been reviewed on RogerEbert.com

in previous festivals. In order of preference:

Cristian Mungiu’s “Graduation” is a brilliantly crafted drama that weds stylistic rigor to a

story that interrogates moral choices in present-day Romania; this one concerns

a doctor and the lengths he will go to to get his daughter to a British

university. (Our review from Cannes)

Cristi Puiu’s “Sieranevada,”

also from Romania, offers a stylistic tour de force in which a ritual family gathering, presented with an

almost anthropological avidity for details, as well as drolly understated wit,

involves conversations touching on everything from 9/11 conspiracy theories to

Romania’s Communist past. (Our review from Cannes)

“I, Daniel Blake,”

the winner of the 2016 Palme d’or at Cannes and the best film in many years

from British stalwart Ken Loach, sums up the bureaucratic miseries of

digital-era England in this tale of disabled worker waging a Kafkaesque battle

to get his health benefits. (Our review from Cannes)

“The Unknown Girl,”

the latest masterpiece by the Dardennes brothers, takes place in their native

Belgium and concerns a young doctor trying to deal with both her own guilt and

an unsolved mystery after a young African immigrant is killed near her office. (Our review from Cannes)

The 54th New York Film Festival runs from September 30 to October 16. Click here for more information.