Across several time zones, enjoying the benefits of hindsight, two critics discuss

Cannes 2014.

MICHAŁ OLESZCZYK: I know you are a fan of the winning Turkish film, Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s “Winter Sleep,” but I don’t seem to be the only one who felt this was a disappointingly middle-of-the-road Palme d’Or. Many people disliked the movie intensely, while some (me included) felt that while certainly interesting, it wasn’t up to the standard that the director’s previous work, like “Distant” or “Once Upon a Time in Anatolia,” had set. What do you think was the jury’s rationale behind this particular choice?

BEN KENIGSBERG: The jurors discussed that a bit at the post-awards press conference. Jane Campion called the film “masterful” and said she would have watched more, despite a 196-minute running time. Even if you don’t feel “Winter Sleep” was one of the highlights of the competition (and for me, it was), it’s clearly was one of the few movies that had its eye on the canon. In theory, the top prize at Cannes should honor a future classic—the next “Blowup,” “Apocalypse Now,” or “Pulp Fiction.” “Winter Sleep” is the sort of fence-swinging, divisive, state-of-the-human-condition film you can see cinephiles debating two decades from now. As strong as much of the competition was, you didn’t see the same sorts of passionate arguments surrounding, say, “Mr. Turner.” Ceylan’s movie is not an easy sit, but I think the passage of time helps to acclimate viewers to the devastation the main character, an Anatolian hotelier named Aydin (Haluk Bilginer), has caused to his family and community.

MO:

It seems to me there’s actually little to debate in the case of “Winter

Sleep”. One either attunes oneself to its slow rhythms or not (I fall into

the latter camp). Once you peel away its showy duration, there’s precious

little here to actually savor—unless the moral dilemmas the movie poses really

resonate with you. I feel funny complaining about this particular movie, since

it was the single title in the competition I had looked forward to the most.

Unfortunately, it felt as if Ceylan was working against his own talents here: The

movie employs long stretches of dialogue, all of which seem written with one

eye not so much on the canon but on a copy of “Uncle Vanya.” In my

opinion, the dialogue is simply too derivative and not deep enough to warrant

the self-important treatment Ceylan employs. As I listened to Aydin going on

and on, I almost heard Ceylan’s keyboard clicking—the lines were just so

strenuously designed to inspire hushed reverence. I’m afraid that this is yet

another Palme d’Or in the lukewarm tradition of “The Best Intentions”

(1992), which won Bille August his (second!) Palme simply because he made an

important movie based on Ingmar Bergman’s script. Just like that had been a

catch-up award at a festival that never gave Bergman the Palme d’Or, this

year’s top prize may be seen as a consolation prize for the maker of “Once

Upon a Time in Anatolia” (which, for me, is superior to “Winter

Sleep” in every possible regard).

BK:

“Anatolia” is a more single-minded and engrossing film, but I think

you’re selling “Winter Sleep” short. I’ll admit that the slow, almost

oppressive pace tried my patience at times, but Ceylan uses it to build a

cumulative effect. For a long stretch, it’s unclear that Aydin’s soul rot will

even be the movie’s subject. What at first seems like curmudgeonly, even comic

behavior—his habit of writing withering op-eds in the local newspaper, for

instance—gradually emerges as symptomatic of a larger personality flaw. So,

too, does Aydin’s seemingly placid relationship with his wife (Melisa Sözen)

eventually come into view as something more sinister; she’s a captive, a victim

of a bad decision made when she was young. (And without giving too much away,

her attempt to compensate for his lack of generosity with his tenants is, by

that point, hopelessly overdue.) The film at first appears to be a community

portrait before revealing its focus as Aydin’s willful, self-imposed isolation;

his malice isn’t contained in any single scene but emerges organically from a

larger picture. Ceylan credits Chekhov as his inspiration, and it seems unfair

to chide him for aspiring to such lofty heights. (The insistence on letting the

audience marinate in three hours of undiluted hopelessness also reminded me of

Eugene O'Neill.) In any case, the movie offers a great deal to chew on, to the

extent that I feel the Palme is much more than just a consolation prize. What

did you think of Andrey Zvyagintsev’s “Leviathan,” which won the

screenplay award and which many observers compared to “Winter Sleep”?

MO:

I like your observation that Aydin’s malice emerges organically from the entire

structure, and is not simply pointed to or revealed in a single scene. Having

said that, I felt that the Chekhovian inspiration was a tad too overt: Ceylan

failed to find his own distinctive voice that would pervade the dialogue and

make it truly distinctive. When you read O’Neill or Chekhov, you get the sense

of rich, imaginative stylization that was lacking here. I think the director

would have fared much better had he just made a straightforward Chekhov

adaptation. At the end of the 196-minute running time, I felt both overfed and

malnourished; the lines felt stale and stifled, the payoff wasn’t there, and

what I did salvage from the film didn’t satisfy me the way the riches of

“Anatolia” did. “Leviathan,” on the other hand, did

something quite opposite: It was so consistent and powerful, by the end of its

hefty 141 minutes I felt as if the titular beast had literally landed on my

head. The film is a purposefully Hobbesian allegory of Putin’s Russia as the

beast devouring its citizens—if anything, I felt the point Zvyagintsev made was

driven home too bluntly. There are brilliant passages in the movie—that

interminable reading of the court sentence is worth price of admission alone—but

there is also repetitiveness that sets in quite early and which I found

tedious. I did appreciate the occasional, very strange sense of humor

Zvyagintsev displays here, but overall I thought the film was just trying too

hard to become an instant classic. That unhealthy craving of instant importance

appeared in extremis in the twin disasters of the festival, namely “The

Search” (by Michel “The Artist” Hazanavicius) and “Jimmy’s

Hall” (by Ken Loach), although I know you have warmer feelings for the

latter than I do.

BK:

I only found “Jimmy’s Hall” watchable when judged by Loach’s abysmal

recent standards—his films have become dry, inert, pedantic. Advocacy has

turned into an end in itself for him. That’s valid, of course, but he seems to

have let artistry fall by the wayside. In this case, even a relatively light

effort about an Irish town rallying around a dance hall in defiance of the

local church somehow seemed bleached of joy. In a similar vein, part of me

admires the fact that Hazanavicius went as far from “The Artist” as

possible in terms of style and subject in “The Search,” remade from a

1948 Fred Zinnemann film, but the movie—about humanitarian work in Chechnya and

a boy separated from his family—is an earnest slog. “Leviathan” is

far more interesting—a rich existential mystery in which one man’s decision to

challenge the Russian political machine in a small town leads to his ruination,

albeit in an oblique way that leaves the question of agency ambiguous. And as

you say, there’s that amazing reading of the court sentence; placed alongside Zvyagintsev’s

other work (“The Return,” “Elena“), the film is practically

a comedy. Did you see Bruno Dumont’s “P’tit Quinquin” in Directors’

Fortnight? It has a similar blend of despair and gallows humor.

MO:

I missed the Dumont, unfortunately, but I couldn’t agree more on the Loach: As

an ardent fan of many of his films, I keep wondering where the energy and

freshness of “Kes,” and even “Sweet Sixteen,” has gone. As

for “The Search,” it managed to be both miserablist and cloying: an

abysmal combo if there ever were one. As bad as it was, I still traced some

similarities to “The Artist,” mostly in the treatment of the little

orphaned boy and his stubborn silence: His first spoken word was almost like

the initial breaking of silence in Hazanavicius’s earlier film. Speaking of

disasters, where do you stand on the near-universally reviled “The Captive,”

in which Atom Egoyan reinvents “Prisoners” by making the most muddled

child abuse thriller in recent memory?

BK:

I guess I felt more charitable than most toward the Egoyan because I’d just

reviewed his disastrous “Devil's Knot,” a dramatization of the original West

Memphis Three investigation that trivializes the case (and often plays like a

distracting facsimile of the documentary footage in Joe Berlinger and Bruce

Sinofsky’s “Paradise Lost” trilogy). Next to “Devil’s

Knot,” “The Captive” was almost a return to form: compelling,

well-crafted, shot with an eye for snow-covered landscapes by regular Egoyan

collaborator Paul Sarossy. But from a moral standpoint, especially given that

Egoyan had just made a movie about

actual child murders, it left me queasy. Even setting aside the plot holes

(is this Internet sex ring entirely based in Canada?), the film presents a

ludicrously sanitized notion of child abduction and its consequences. The

relentlessly civilized kidnapper listens to classical music and keeps his

captive in a posh, high-tech basement room; the abuse victim doesn’t seem

traumatized at all. Egoyan tacked child loss with much more nuance—and a

productive sense of indirection—in his vertiginous “Exotica” (1994)

and “The Sweet Hereafter” (1997). The festival’s closest equivalent

to those might be David Cronenberg’s “Maps to the Stars”—though

that’s perhaps a stretch.

MO:

Now, here’s a film by yet another Canadian dealing with touchy issues, but

doing it with so much panache, I found myself completely seduced. I don’t think

Cronenberg is getting enough credit for bravely reinventing himself in his

recent projects—it’s almost as if everyone were stuck with the notion that he

has to repeat obsessive body horror patterns. “Maps to the Stars” is

a horror movie, of sorts: Not unlike “Leviathan,” it projects a world

of total corruption and ruthlessness, but employs glee in lieu of gloom. The

idea that Hollywood (or, as my friend Steven Boone calls it, Ho’wood) is a

place in which maturity doesn’t exist and one is stuck in eternal repetition of

childhood got a supreme treatment in Bruce Wagner’s explosive script.

BK:

For me, Wagner’s script was problematic, a would-be tell-all indictment of

Hollywood written by someone who doesn’t seem to show even a basic

understanding of how Hollywood works today. But if the movie’s theme is, as you

say, “eternal repetition,” then it may be deliberate that the

satire comes across as secondhand, derived more from other movies about washed-up

actors (Julianne Moore deserved that prize, by the way) and troubled child

stars than from any real knowledge of the entertainment industry. Certainly,

the film disturbs with its Cronenbergian body horror (a traumatic childhood

incident has left Mia Wasikowska’s character deformed) and a literally

incestuous family dynamic. This is a case where I need a second viewing. Which

Cannes title are you most looking forward to seeing again?

MO:

In Wagner’s defense: Joe Mankiewicz’s script for “All About Eve”

didn’t show much understanding for real theater either—it was its stylized view

of craving and malice that made it into a masterpiece. “Maps to the

Stars” is as much a fervid dream of Hollywood madness as “The Bad and

the Beautiful” and “Mullholland Dr.,” and I also look forward to

repeated viewings of it, since it was probably the second-most textured film at

the festival. The most textured one, as well as my favorite and the one that

answers your question, was Mike Leigh’s “Mr. Turner.” Despite few

tiny missteps (notably the ending, which fizzes away a bit too easily), this is

a rare feat: a period piece that doesn’t condescend to the chosen period by

putting it in the heavy quotation marks of overdramatization, undue reverence,

or covert derision fueled by the privilege of hindsight (“Mad Men”–style).

It presents the past as just as corrupt, unjust, and/or honorable as our

present, and it does justice to the titular character (the great British

proto-Impressionist painter J.M.W. Turner) by not turning him into a dull icon

of “creativity.” A stunning film.

BK:

What I especially liked about “Mr. Turner” was that it seemed less

concerned with Turner’s painting technique than with his personality; it shows

you the kind of prickly attitude an artist of his era would need in order to

challenge conventions in the face of ridicule. I don’t think Cronenberg’s movie

as anywhere near as elegant as “The Bad and the Beautiful” or

“Mulholland Dr.,” though the latter is probably the more relevant

comparison, in that—like “Stars”—it’s set in Hollywood but not about

it. Instead, it’s a fever dream constructed out of an elaborate internal

mythology. To the extent that “Maps” coheres, it’s really as an

amalgam of some of Cronenberg’s recent obsessions: double identities, Oedipal

angst, madness and violence as underpinnings of the family. As for “All

About Eve,” there’s a pronounced echo of that film in Olivier Assayas’s

“Clouds of Sils Maria”—the last competition title to screen for the

press and one of the least discussed, despite being, to my mind, hypnotically

strange. Did you like it?

MO:

I’m a fan of Assayas, but the strangeness you mention remained almost entirely

unrealized for me. The story itself is a borderline-cliché, with a lineage

taking us as far back as “All About Eve,” “Persona,” “The

Bitter Tears of Petra Von Kant,” or “Opening Night“: an aging

actress is drawn into a power struggle with a newcomer, who seems to be her

opposite number, but is in fact her mirror self. Assayas’s script is too

platitude-laden to support the notion of a powerful personality at war with

itself, though. For long stretches, I didn’t know how to take it: as a straight

but poorly written two-hander or as a near-campy exercise in faux-gentility

that was far more self-conscious than I first gave it credit for. Critic Guy

Lodge put it well in his post-screening tweet: “CLOUDS OF SILS MARIA: Too

silly or not silly enough?” Did you like the movie?

BK:

I did, but not as much as “Opening Night” or “Bitter

Tears.” I think you’re oversimplifying a bit, though, in that the contrast

the movie sets up is not just between the aging actress, Maria Enders (Juliette

Binoche), and the young star (Chloë Grace Moretz) who takes on her signature

role, but also between Maria and her personal assistant (Kristen Stewart, who’s

a real surprise here). As they hike through the Swiss Alps, there are long

stretches in which there’s an ambiguity as to whether they’re rehearsing

Maria’s lines or actually talking to each other. There’s also a

“Persona”-esque narrative rupture that we shouldn’t discuss, but it

caught me off-guard. Part of what separates “Clouds of Sils Maria”

from the films it alludes to is its relative serenity about aging. Assayas has

said that the project grew out of an early collaboration with Binoche, so

there’s a self-reflexive aspect as well. I can see how you found it under-realized—I

expected more in the way of narrative incident, personally—but I think this is

another instance of the kind of delicately layered film that always plays

better away from the exhaustion of a festival context.

MO: I would be very

reluctant to revisit this particular movie (unlike, say, “Winter Sleep,”

which I believe may improve upon repeated viewings, even though I have so many

reservations about it). Stewart is very good in “Clouds of Sils Maria,”

but I found her a mere conceptual extension of the Moretz character (which

assistant learns all the lines of the play her boss is rehearsing?). The scenes

of their long shared sessions, in which they may or may not be quoting the

play-within-the-film, struck me as tedious, also because the material they are

working on is so self-explanatory and thin. Am I really to believe the

greatness of the “Maloja Snake” based on those tinny passages on

domination and sexual resentment we hear being quoted? I was at a loss most of

the time, also because the movie so blatantly denies any connection to

recognizable social and economic reality: It’s all lofty dilemmas, expensive

dinners, and upper-bourgeois pretension, which was almost shocking to see at a

festival at which many movies, most notably “Two Days, One Night,”

were trying to make a comment on our ruptured economic reality of global

recession. Had there been riches of insight here, I would have given it a pass,

but the film seemed insular and limited in its view of the characters’ lives.

BK:

Well, at a festival as large and varied as Cannes, I think there’s room for

both bourgeois pretension and social-justice

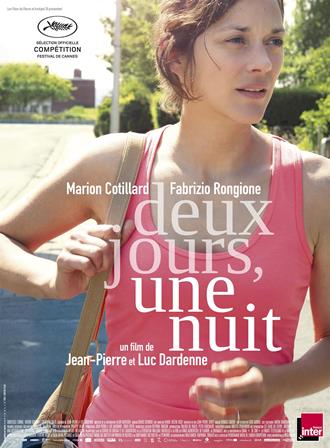

drama. But I do love the Dardenne brothers’ “Two Days, One Night,” in

which the main character, Sandra (Marion Cotillard), is forced to fight for her

job by earning her coworkers’ votes; they’ve been given a choice between taking

a 1,000-euro bonus each or allowing her to stay on. One of the striking things

about the situation—and I know you found the setup implausible, but I think

it’s meant to be read metaphorically—is that the managers of the company have

delegated their responsibility for the layoff, pitting their working-class

employees against each other. Initially, it appears that Sandra’s mostly unseen

boss, Jean-Marc, has been making phone calls to sway the vote against her, but

there’s also the suggestion that her colleagues may be lying about the external

pressure, and that their self-preservation instincts are ingrained. It’s

significant that Sandra works in solar power—a clean, modern, ostensibly

growing industry that nevertheless here runs according to the bottom line (and

that conceals toxic workplace interactions). On a macro level, the film functions

as a not-at-all-subtle commentary on EU politics.

MO: I rather liked the movie,

but couldn’t help thinking that it lacked the subtle power of Dardennes’

earlier masterpieces, such as “Rosetta,” “L'Enfant,” and (yes) “The Kid With a Bike.” Casting Marion

Cotillard is too conspicuous a decision for me: The movie attempts topical

urgency that’s achieved at the cost of subtlety, texture, and plausibility. I

really don’t see why a small-company employer would risk alienating his staff

by organizing this scapegoat-hunt of a vote. (We are not speaking of a huge, faceless

corporation here, but of a company in which everyone knows each other on

first-name basis.) The movie fails to raise uncomfortable questions like the

quality of the work Cotillard’s character has been doing so far, or the fact

that this is ultimately a reasonably well-off, white European woman whose

greatest fear is going back to live in the projects. Personally, I thought some

of the immigrants shown in the movie (all looked upon in passing), would be

worthier subject of a hard-hitting political film in the vein of Dardennes’ own

“La Promesse.”

BK: You can’t claim that

race is not an issue in the film. One of the colleagues Sandra must persuade is

a black contract worker who, because of his short-term status with the company,

has far more at risk than she does. As for why the bosses would consider alienating

their employees, I think part of the point is that the employees don’t become

alienated. They never rally around Sandra or fight back but instead retrench to

advocating for their own interests. Have you ever seen two people compete for

the same promotion? It gets ugly.

MO:

The black contract worker is a blind spot of the

script: He tells Sandra how afraid he is of his vote being made known to the

other workers, after which we see him openly gathering with everyone who voted the

same way (that scene in fact makes very little sense, since for the entire film

we kept hearing the vote will be held in secrecy). Of course competition can

get ugly, but I don’t quite see what the incentive would be for a

small-business owner to organize a vote as blatantly unfair as this one.

Speaking of small business, there was a family of Italian beekeepers in Alice

Rohrwacher’s “The Wonders,” which was probably the single greatest

surprise of this festival for me. I hated the director’s previous film,

“Corpo Celeste,” which was a crass satire of organized religion (the poor

man’s “Lourdes,” so to speak), but this one is just about perfect.

The portrayed family runs its organic farm as an unphotogenic junkyard; the

relationships within the group are strained and edgy, while the style of

filming is very raw and uninviting at first. But as the story progresses and

zeroes in on a tacky TV contest the family enters at one point, I felt more and

more attached to the characters. Monica Bellucci’s fantastic, subdued cameo

notwithstanding, this is a movie in which an alternative lifestyle receives

validation, life, and unsentimental beauty—it’s a far subversive work than

Cotillard doing her best “Norma Rae” impersonation in defense of what

is in fact a comfortable middle-class lifestyle.

BK: “The Wonders”

was a nice surprise, but I don’t see myself revisiting it years from now the

way I can “Two

Days, One Night” or “Winter Sleep.”

The perennial problem with Cannes is that you attend

expecting masterpieces, which means that any flaws—the Dardennes picture was not subtle enough, in your estimation,

though not mine—become magnified. I didn’t see anything I’d call a revelation,

but on the whole, I think we can agree that it was a pretty good year.