“Sweet Sixteen” is set in Scotland and acted in a local accent so tricky it needs to be subtitled. Yet it could take place in any American city, in this time of heartless cuts in social services and the abandonment of the poor. I saw the movie at about the same time our lawmakers eliminated the pitiful $400 per child tax credit, while transferring billions from the working class to the richest 1 percent. Such shameless greed makes me angry, and a movie like “Sweet Sixteen” provides a social context for my feelings, showing a decent kid with no job prospects and no opportunities, in a world where only crime offers a paying occupation.

Yes, you say, but this movie is set in Scotland, not America. True, and the only lesson I can learn from that is that in both countries too many young people correctly understand that society has essentially written them off.

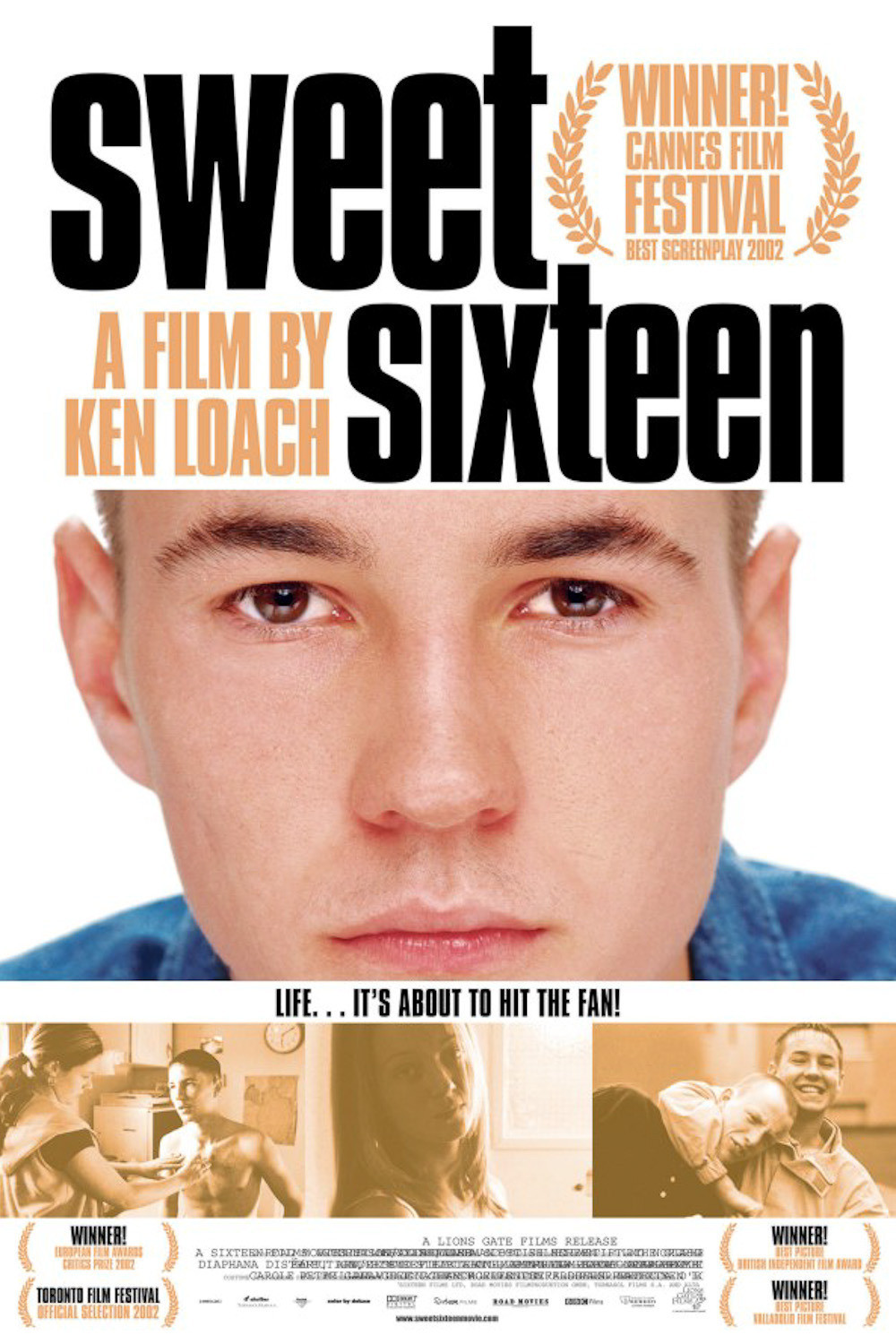

The director of “Sweet Sixteen,” Ken Loach, is political to the soles of his shoes, and his films are often about the difficulties of finding dignity as a working person. His “Bread and Roses” (2000) starred the future Oscar winner Adrien Brody as a union activist in Los Angeles, working to organize a group of non-union office cleaners and service employees. In “Sweet Sixteen,” there are no jobs, thus no wages.

The movie’s hero is a 15-year-old named Liam (Martin Compston) who has already been enlisted into crime by his grandfather and his mother’s boyfriend. We see the three men during a visit to his mother in prison, where Liam is to smuggle drugs to her with a kiss. He refuses: “You took the rap once for that bastard.” But the mother is the emotional and physical captive of her boyfriend, and goes along with his rules and brutality.

The boy is beaten by the two older men, as punishment, and his precious telescope is smashed. He runs away, finds refuge with his 17-year-old sister Chantelle (Annmarie Fulton), and begins to dream of supporting his mother when she is released from prison. He finds a house trailer on sale for 6,000 pounds, and begins raising money to buy it.

Liam and his best friend, Pinball (William Ruane), have up until now raised money by selling stolen cigarettes, but now he moves up a step, stealing a drug stash from the grandfather and the boyfriend and selling it himself. Eventually he comes to the attention of a local crimelord, who offers him employment–but with conditions, he finds out too late, that are merciless.

Some will recall Loach’s great film “Kes” (1969), about a poor English boy who finds joy in training a pet kestrel–a season of self-realization, before a lifetime as a miner down in the pits. “Sweet Sixteen” has a similar character; Liam is sweet, means well, does the best he can given the values he has been raised with. He never quite understands how completely he is a captive of a system that has no role for him.

Yes, he could break out somehow–but we can see that so much more easily than he can. His ambition is more narrow. He dreams of establishing a home where he can live with his mother, his sister and his sister’s child. But the boyfriend can’t permit that; it would underline his own powerlessness. And the mother can’t make the break with the man she has learned to be submissive to.

The movie’s performances have a simplicity and accuracy that is always convincing. Compston, who plays Liam, is a local 17-year-old discovered in auditions at his school. He has never acted before, but is effortlessly natural. Michelle Coulter, who plays his mother, is a drug rehab counselor who also has never acted before, and Annmarie Fulton, who plays the sister Chantelle, has studied acting but never appeared in a film.

By using these inexperienced actors (as he often does in his films), Loach gets a spontaneous freshness; scenes feel new because the actors have never done anything like them, and there are no barriers of style and technique between us and the characters. At the end of “Sweet Sixteen,” we see no hope in the story, but there is hope in the film itself, because to look at the conditions of Liam’s life is to ask why, in a rich country, his choices must be so limited. The first crime in his criminal career was the one committed against him by his society. He just followed the example.

Note: The flywheels at the MPAA still follow their unvarying policy of awarding the PG-13 to vulgarity and empty-headed violence (“2 Fast 2 Furious“), while punishing with the R any film like this, which might actually have a useful message for younger viewers.