How is it that the same movie can seem tedious on first viewing and absorbing on the second? Why doesn’t it grow even more tedious? In the case of “Distant,” which I first saw at Cannes in 2003, perhaps it helped that I knew what the story offered and what it did not offer, and was able to see it again without expecting what would not come.

The film takes place in Turkey, but its dynamic could be transplanted anywhere — maybe to our own families. It is about a cousin from the country who comes to the big city searching for work and asks to stay “for a few days” with his relative, who is a divorced photographer with walls filled with books and an apartment filled with sad memories.

Mahmut (Muzaffer Ozdemir) is the photographer, whose wife has divorced him and is marrying another man; the couple will move to Canada. What went wrong is not hard to guess: Mahmut is a man of habit, silent, introspective, exhausted by life. Yusuf (Mehmet Emin Toprak) comes from a town where the factory has failed, and there are no jobs; he foolishly thinks he can get hired on one of the ships in the port, but there are no jobs, and an old sailor informs him that the wages are so bad, he’ll never have anything left over to send home.

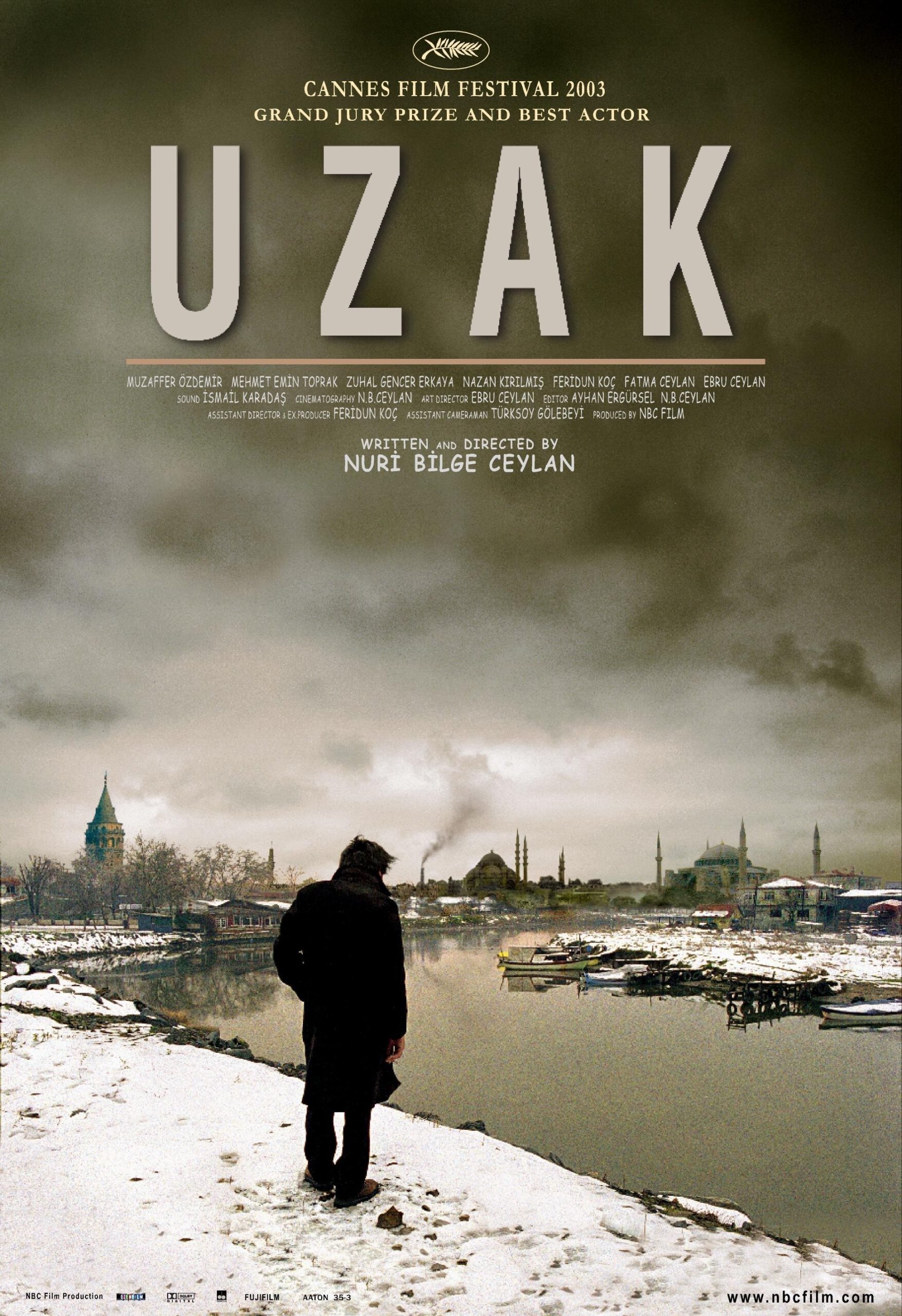

It is the dead of winter. Yusuf tramps through the snow with no gloves and inadequate shoes, and his job search starts unpromisingly when the first ship he finds is listing and sinking. He haunts the coffee bars of the sailors, who smoke and wait. Mahmut, meanwhile, says goodbye to his wife and then secretly and sadly watches her leaving from the airport. He has a shabby affair with a woman who lives nearby and who will not make eye contact in a restaurant. He watches art videos (Tarkovsky, I think) to drive Yusuf from the room and then switches to porno.

For both men, smoking is a consolation, and they spend a lot of time standing alone, doing nothing, maybe thinking nothing, smoking as if it is a task that provides them with purpose. Mahmut has rules (smoking only in the kitchen or on the balcony), but Yusuf sits in his favorite chair and smokes and drinks beer when Mahmut is away, and Mahmut grows gradually furious at the disorder that has come into his life. “Close the door,” he says as Yusuf goes to the guest bedroom, because he wants to shut him away from his privacy.

A photographic expedition to the countryside, with Yusuf hired as his assistant, turns out badly for Mahmut; sharing rented rooms, they invade each other’s space. Finally, Mahmut has had enough and asks Yusuf, “What are your plans?” But Yusuf has none. He does not even have an opening for plans. He is trapped in unemployment, has no money, no skills, no choices.

The film, directed by Nuri Bilge Ceylan, is shot with a frequently motionless camera that regards the men as they, frequently, regard nothing in particular. It permits silences to grow. Perhaps in the hurry of Cannes, with four or five films a day, I could not slow down to occupy those silences, but seeing the film a second time, I understood they were crucial: There is little these men have to say to each other and — more to the point — no one else for them to talk with. Women are a problem for them both. Yusuf shadows attractive women but is too shy to approach them before they inevitably meet a man and walk off arm-in-arm. A man without funds is in a double bind: He has no way to attract good women or to hire bad ones. The one sex scene we witness with Mahmut, which is out of focus at the far end of a room, is so joyless that solitude seems preferable.

A movie like this touches everyday life in a way that we can recognize as if Turkey were Peoria. I can imagine a similar film being made in America, although Americans might talk more. What do you say to a relative who is out of work and seems unlikely to ever work again? He is family, and so there is a sense of responsibility bedded in childhood, but there are no jobs and he has no skills, and your own comfort, which seems so enviable to him, is little consolation to you. To have joyless work means you have employment but not an occupation. At the end, one of the men is sitting on a bench on a gray, cold day, staring at nothing, and if we could see the other man, we could probably see another bench. “Distant” is a good title for this movie.

Note: At Cannes, the movie won the Jury Grand Prize, and Ozdemir and Toprak shared the prize as best actors. The previous December, Toprak died in a traffic accident. He was 28.