CANNES, France –- All rumors about the prizes at Cannes are essentially worthless. Why don’t I know this? I could make up my own and do just about as well. It is apparently true that Sam Jackson told somebody there were going to be “big surprises” when the awards were announced, and there were; never before has a jury honored the casts of two films with ensemble acting awards, and certainly no one predicted that Ken Loach’s “The Wind That Shakes the Barley” would win the Palme d’Or. When it did, there was much agreement, and, yes, much surprise.

But the prognosticators were looking for bigger surprises than that. Sunday morning in the Hotel Splendid breakfast room, my favorite Cannes expert Pierre Rissient predicted that the big prize would shock everyone by going to “Colossal Youth,” by the Portuguese director Pedro Costa. Pierre is such a legend they are naming a theater after him at Telluride this year, but he was, to put it delicately, wrong.

“Colossal Youth,” unseen by me, tells the story of a Lisbon worker whose wife leaves him, and he moves from a slum to a housing complex. Why didn’t I see it? Because Mary Corliss did. She is the wife of Time film critic Richard Corliss, who told me: “Mary walked out after an hour because the movie made her feel like rats were fighting in her skull.”

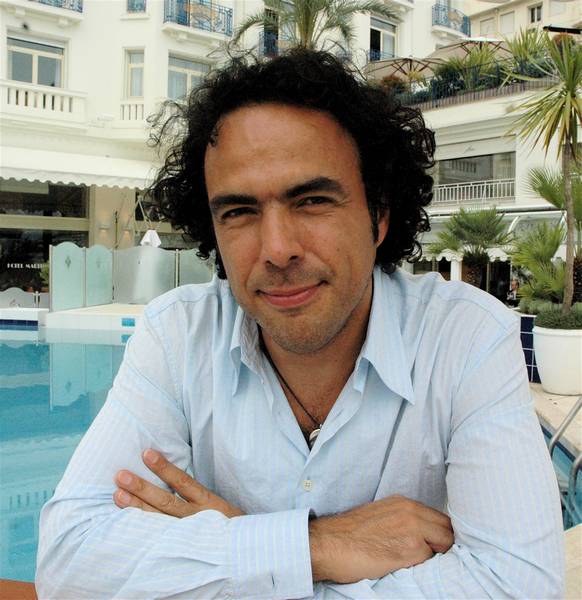

Two other films mentioned as Palme candidates, Pedro Almodovar’s “Volver” and Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu’s “Babel,” did win major prizes: “Volver”’s entire cast, led by Penelope Cruz and Carmen Maura, was honored, and he won for screenplay. “Babel” won for best director.

But what about another much-touted film, Sofia Coppola’s “Marie Antoinette?” No other film was so loved by the French critics, although of course they are not the jury. And as the festival came to its close, I found the film growing in my memory and appreciation. Others said the same: Once you get over the surprise that there’s no beheading, you step back and realize what a stunning visual achievement it is, and how well Kirsten Dunst plays a 14-year-old girl who grows up into her fate and doom.

I thought the jury might give “Marie Antoinette” an award in part to correct the impression that the film was booed out of town. As I wrote earlier, the booing at the press screening (five or 10 people, maybe) was blown up into a scandal. On balance, audiences here admired the film – some of them, a lot.

Another incorrect rumor, but one with a lot of passion behind it, was that Guillermo Del Toro’s “Pan’s Labyrinth,” might charge out of nowhere on the last day of screenings and grab the Palme d’Or. Not shown until Saturday (the last day for competition screenings), it would have been a worthy winner, a fairy tale for grown-ups that has surprising emotional power.

It takes place in 1944, as Franco’s fascist regime holds control in Spain but the Nazis are facing the world-changing reality of the Normandy landings. In an isolating forest outpost, a band of fascist soldiers hunt down a band of rebels who are still holding out. The officer in command (Sergi Lopez) is a ruthless sadist. His new wife has a daughter named Ofelia (Ivana Baquero) from an earlier marriage, and this daughter is led by a fairy into a labyrinth where a fearsome faun tells her of her role in the Underworld Kingdom.

Del Toro (“Cronos,” “Blade II,” “Hellboy“) once again shows his mastery of serious fantasy as a genre, and despite fairies and fauns this is a serious movie. Also beautiful and exhilarating, with a payoff that combines emotion with magic and is astonishingly moving, considering it involves giant toads. The cinematographer Guillermo Navarro makes the movie’s fantasy elements dark and painterly. That “Pan’s Labyrinth” and “Marie Antoinette” didn’t win some sort of prize is surprising.

The very last film I saw at Cannes was a three-hour restoration of Giovanni Pastrone’s “Cabiria” (1914), an early silent epic, awesome in ambition. In a filmed introduction, Martin Scorsese says it was this film, a worldwide hit, that inspired great leaps forward by D.W. Griffith and Cecil B. DeMille, directors often given credit for Pastrone’s innovations. He was perhaps the first to use a moving camera, his sets anticipated the colossal constructions in DeMille’s epics, and in Maciste (Bartolomeo Pagano), the giant strongman, he created the first Italian movie star; Pagano changed his name to Maciste, and starred as the North African Hercules in 24 more films.

One spectacular scene in the film shows a city’s walls being scaled. Eight warriors bend over and balance their shields on their backs. Six more stand on the shields, bend over, and balance their own shields. Then four, then two, until finally the hero scales this pyramid of men and shields and reaches the top of the wall, in a splendid demonstration of how a film wins at Cannes.