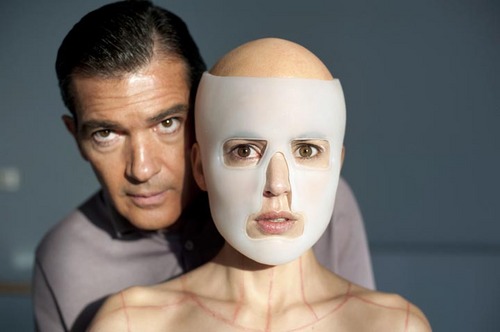

This morning, Pedro Almodovar, Spain’s biggest big-cheese filmmaker, handed us a limp noodle with “The Skin I Live In,” his entry in the Cannes competition. The film stars Antonio Banderas (who began his career in Almodovar’s early films) and Elena Anaya, who looks like a cross between Penelope Cruz and Audrey Hepburn. Even a second-best Almodovar film has its delicious moments, but “The Skin I Live In” is flat compared with his best work, including “Broken Embraces,” “Volver,” and his Oscar winner “All About My Mother.”

Typical of Almodovar, the film is a melodramatic farce. Although it’s based on the novel “Mygale” (“Tarantula” in English) by Thierry Jonquet, the story is also strongly reminiscent of the 1960 French horror classic “Eyes Without a Face” by Georges Franju. In the Franju film, a surgeon kidnaps women in order to graft their faces onto the head of his disfigured daughter. In “The Skin I Live In,” a plastic surgeon is engaged in highly experimental work in order to create synthetic skin as a tribute to his dead wife, who was burned to death in a car crash. He subsequently uses the results of his research in service of a unique punishment for his daughter’s rapist.

This story has a lot of twists, and the element of surprise is important. I don’t want to give away too much, especially since it’s due to open in the U.S. in the fall. I haven’t read “Mygale,” but I understand that the narrative is fragmented into sections that all come together in the end. In this, Almodovar appears to have followed the structure of the book, perhaps too closely. One of the principle weaknesses of “The Skin I Live In” is that the story is scattered in pieces. Characters and subplots are introduced then dropped. They are loosely but not completely tied together in the end.

Dr. Robert Ledgard (Banderas) is a control freak who lives in a mansion with his tough, protective housekeeper Marilia. Robert’s advanced work is highly respected in his profession, but there are whispers about his methods. Due to the fact that some of his experimentation involves unapproved techniques, he maintains a laboratory and private operating room in his home, where special clandestine procedures are carried out on patients who don’t go by their real names.

Marilia has a few secrets too, and one of them involves a wild man of a robber, who shows up at the door in a tiger costume. This particular subplot, which appears early in the film, is soon dropped without a trace. Central to the story is Almodovar’s trademark gender-bending, involving a lovely but suicidal patient who is required to wear a flesh-colored bodysuit to protect her new skin. There are flashes of the director’s wit and flamboyant fashion sense, and one or two laugh-out-loud moments, but I missed cohesion and the genuine poignancy.

Speaking of control freaks, the guards in the Palais manage to fill that role daily. The seating in the two main theaters is strictly segregated by level of pass. Audience members are channeled to their designated areas, and heaven forbid that anyone would try to cross the lines of the Cannes hierarchy. Viewers in the balcony, where the blue passes sit, frequently attempt to sneak down one of the staircases at the side of the main floor where the white and pink passes sit. Each and every time they are driven back by the guards, who remind me of lion-tamers with imaginary whips and chairs.

Power is the subject of the French film “The Minister” by Pierre Schoeller, a political drama in Un Certain Regard that centers on a man who is in the process of having his soul re-shaped by the pressures of holding public office. Bertrand Saint-John, the Minister of Transportation and would-be reformer, is put in the spotlight by a horrific bus accident that kills many children, and by a host of hot-button national issues. His has yet to make a misstep and is considered a rising star in government except for one flaw–no one is sure where his true political loyalties lie.

“The Minister” is a fast-paced film, whether set at a chaotic accident site or behind closed doors. It portrays the business of governing as largely one of manipulating the media and managing public opinion. Government officials are seen as no less ruthless than the media sharks that go after them. The film opens with its most arresting and metaphorical image, which is Saint-John’s nightmare: a naked woman crawls across the oriental carpet of an opulent office and into the open jaws of an alligator.

There are no lion-tamers, alligators, sharks or other symbolic references in “This Is Not a Film“ by Jafar Panahi and Mojtaba Mirtahmasb, a film that needed no embellishment to expose one filmmaker’s brave stand against ruthless power. Panahi (“Offside,” “The Circle,” The White Balloon”) is the Iranian filmmaker who, along with Mohammad Rasoulof (“Goodbye,” “White Meadows”) has been sentenced by the Iranian government to serve six years in prison, and is banned from directing films for twenty years. Despite that ban, he has submitted “This Is Not a Film” to Cannes.

“This Is Not a Film” is a documentary, a home movie, really, filmed in March of this year, recording one day in Panahi’s life. The director is confined to his home under house arrest, pending the outcome of his appeal. The day happens to be the holiday Fireworks Wednesday, a kind of Persian New Year’s eve, when bonfires are lit in the streets and the sound of fireworks makes the city sound like a war zone. His family is away for the day, and Panahi is alone except for Mirtahmasb with the camera.

The film begins by following Panahi in a daily routine: breakfast; getting dressed; feeding his daughter’s pet iguana Igi; and taking a call from his lawyer (who is hopeful that the ban on working will be lifted following the appeal, but not so hopeful about a significant reduction of the prison sentence). In the background on TV, a newscaster reports that Iran’s supreme leader has denounced Fireworks Wednesday as “unreligious.”

In the middle section of the film, Panahi gets out his most recent banned script and proceeds to block out scenes in his living room while describing the story of a young woman whose religious family locks her up to prevent her from registering for the university. He points out that the ban prevents him from directing, but not from reading a script out loud or acting. He can’t resist calling out “Cut” at points, but Mirtahmasb mildly reminds him, “You are not directing; it’s an offense.”

In the final section of “This Is Not a Film,” night has fallen and Mirtahmasb departs, but only after leaving the camera turned on. In the film’s significant gesture of defiance, Panahi becomes a filmmaker once again, taking the camera to follow and film his extended conversation with a young janitor’s assistant as they ride the elevator from floor to floor collecting trash. It’s a funny and halting conversation with a triumphantly defiant conclusion. Panahi steps outdoors with the camera and shoots the holiday night scene, where a massive bonfire burns like a torch just outside the gate to his condo building.