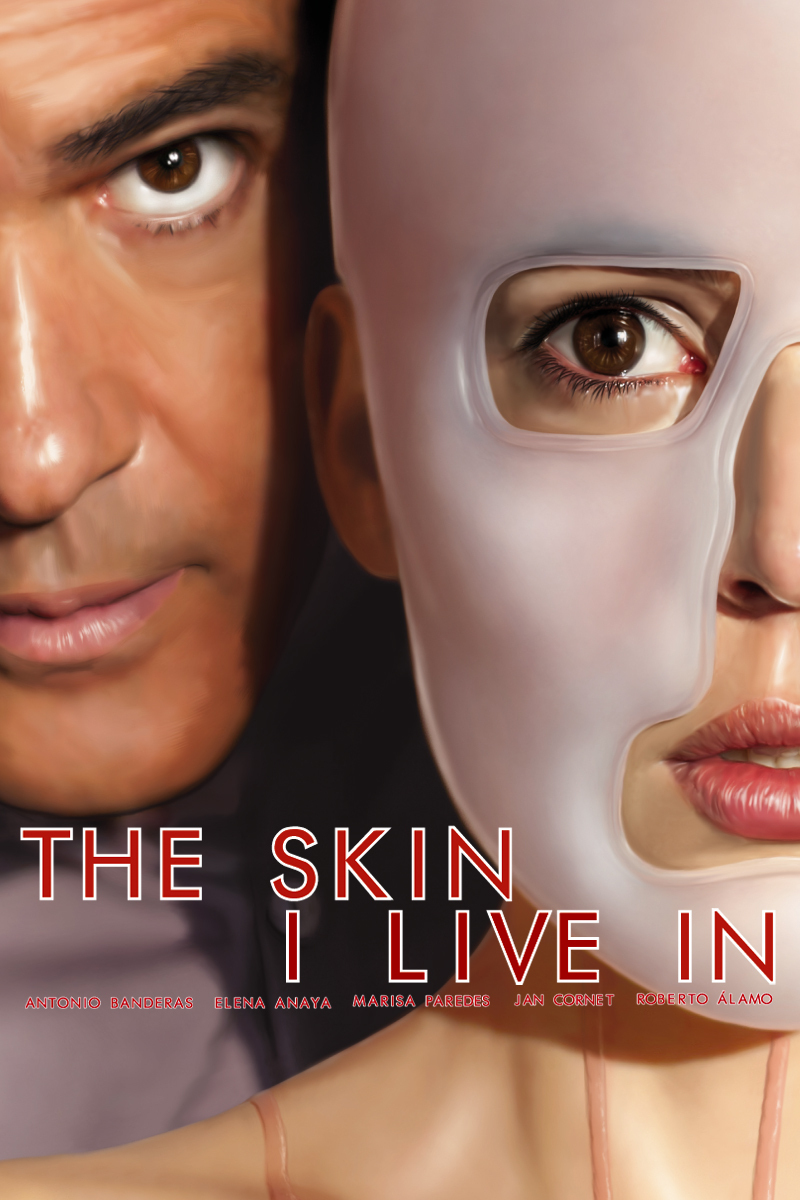

With a Pedro Almodovar film, we expect voluptuous sexual perversion, devious plot twists, a snaky interweaving of past and present, all painted on a canvas of bright colors with bold art and clothing. His latest film, “The Skin I Live In,” does not disappoint. Though I usually take pleasure in Almodovar’s sexy darkness, this film induces queasiness.

What it provides is a glossy, smooth, luxurious version of the sorts of unspeakable things that occupied classified classic horror films involving mad scientists, body parts, twisted revenge, personal captives and hidden revenge. Usually such films are stylistically elevated enough that there’s an irony involved, a camp humor.

Although camp is not unknown to Almodovar, here he maintains an emotional intensity showing that his bizarre story must be taken seriously. Yes, there is a mad scientist: the driven, brilliant Dr. Robert Ledgard, played by Antonio Banderas with rare intensity. Robert is driven by his science to try to repair tears in his heart. To do this, he assumes he has the godlike right to use the bodies and minds of other people: Their sacrifices are necessary to heal his pain.

As the film opens, he holds the beautiful Vera (Elena Anaya) captive in his huge mansion in the Spanish city of Toledo. She has every luxury except freedom. She is dressed from toes to chin in a flesh-colored costume that looks like a compression suit. She has a stack of books, a routine of yoga, around-the-clock service, everything but her freedom. She is not his patient but his prisoner, and perhaps she believes there are only two ways to free herself: suicide, or forcing the doctor to fall in love with her. She is narcissistic enough to know how beautiful she is, and seduction is a challenge to her.

We learn pieces of the back story. Robert’s young wife was horribly burned in a car accident. His specialty has become face transplants. (“I have performed three of the nine in history, and nothing has given me more satisfaction.”) I briefly thought Vera was his wife, but no, she’s dead, and Vera was kidnapped. He watches her on closed-circuit TV like an artwork and seems intent on using plastic surgery to create an ideal woman who will be, to put it plainly, fireproof.

There’s much clinical detail involving laboratory work, cloning, the blood of living pigs and sheets of newly grown skin. Some sequences could come from a documentary. This program of surgery is embedded in a plot so devious that the audience knows more than Robert ever does — for example, the identity of his mother and his brother. That’s Almodovar for you: It makes no difference who those people are, or whether Robert knows it. Pedro is just thickening the soup.

There is also a rape the nature of which Robert misunderstands. And the faithful older housekeeper Marilia (Marisa Paredes), who all mad scientists are required to have on staff. And Zeca (Roberto Alamo), a man dressed as a tiger, who comes to the house and explains to Marilia that he is a wanted man, and must be given sanctuary; only during Carnival can he move through the city disguised as a tiger. And Vicente (Jan Cornet), who Robert kidnaps for mistaken reasons and holds captive in the basement. You see how this film could have starred Vincent Price.

It looks so silky. Few directors have used colors, especially red, as joyfully as Almodovar. Every scene vibrates. There is passion, but not chemistry; although we believe Vera actually does hope to seduce the doctor, his feelings for her seem psychopathic, not sexual. He wants to prove something. The full depth of his depravity is revealed in the unexpected final sequence, when we discover that Robert’s emotional engine is fueled not by lust, jealousy or anger, but by a need to treat others as his scientific playthings.

Robert is an unwholesome character. The feelings of others mean nothing to him. That he expresses them on the rich canvas of Almodovar lends them a superficial beauty, but he is rotten to the core. This film must be credited with expressing exactly what Almodovar wanted to say, but I am not sure I wanted to hear it. The three-star rating is a compromise between admiration for the craftsmanship and the acting, and disquiet about the story.