Pedro Almodovar loves the movies with lust and abandon and the skill of an experienced lover. “Broken Embraces” is a voluptuary of a film, drunk on primary colors, caressing Penelope Cruz, using the devices of a Hitchcock to distract us with surfaces while the sinister uncoils beneath. As it ravished me, I longed for a freeze frame to allow me to savor a shot.

The movie confesses its obsession upfront. It is about seeing. A blind man asks a woman to describe herself. Since we can see her perfectly well, one purpose of this scene is to allow us to listen to her. How to describe the body, the hair, the eyes? Movies are really about the human body more than anything else. I was recently faulted for lingering overmuch on Ingrid Bergman’s lips in “Casablanca.” Anyone, man or woman, who doesn’t want to linger on Ingrid Bergman’s lips is telling us something about themselves we’d rather not know.

The blind man is Harry Caine (Lluis Homar). Harry Lime and Citizen Kane, get it? Both played by Orson Welles, the great man of the cinema. Welles, whose “Magnificent Ambersons” was infamously botched by being re-edited in his absence. Harry Caine is the name Mateo Blanco takes after being blinded in an automobile accident. Perhaps only he knows why. As Blanco, he directed a film named “Girls and Suitcases.” It was produced by a man named Ernesto Martel (Jose Luis Gomez). Harry/Mateo hates Martel for reasons that will be explored.

One day Caine is visited by Ray X (Ruben Ochandiano). X-Ray: yeah, you got it. X despises the memory of his father and wants to enlist Caine, now a famous writer, to do the screenplay. Perhaps Ray X has hidden reasons for contacting him.

Guarding Caine in his blindness is Judit (Blanca Portillo), who was his trusted aide when he could see and has now become indispensable. It is clear, although she has never revealed it to him, that she loves him. We sense her feelings go beyond love, however, into realms he doesn’t guess.

Years ago, when Martel and Blanco/Caine were preparing “Girls and Suitcases,” the producer hired his mistress Lena (Cruz) as his assistant. In the time-honored tradition of such arrangements, in particular when the woman has been a prostitute, a producer will allow such a person to audition, and so Martel arranges for Lena to audition for a role in the new picture. But the director falls in love with her during the screen test.

Martel is enraged as only a rich middle-aged man who has purchased love can be. He sics his son on them. Yes, the future Ray X follows them with his camera like a nerdy fanboy. That it’s unwholesome to spy on the behavior of your father’s mistress goes without saying; can the boy be blamed of growing up to hate Martel? His videos are screened for the father, who combines jealousy with voyeurism, a common enough mixture.

I’ve really only scratched the surface of where “Broken Embraces” goes and what it discovers. To find that this passion comes to fruition in a blind man’s editing room is to demonstrate that all films, and all of us, are blind until the pieces are put together. There are two, or really four, movies within this one: Martel’s film in its first and second cuts, and Ray X’s video seen one way and then another. The nature of each film changes in transition, and the changes have deep meaning for the characters.

Look at Almodovar’s command of framing here. There’s one unbroken shot so “illogical” it may even slip past you. There’s urgent action on a sofa in the foreground and then a character stands and moves to the right, talking, and dawdles slightly and then moves to the left, and now we see for the first time the next room completely open to this one, and there is a young man seated at a table.

What? He must have been there all along, yet the foreground action took no notice of him, the camera didn’t establish him, and now no acknowledgement is made of his incongruous presence.

I think this shot may be about the ability of camera placement and film editing to dictate absolutely what is and is not in a scene. I’m sure it also has meaning in terms of the characters, but I don’t know what. It shows Almodovar saying he’ll do things just for the hell of it and manage to keep a straight face.

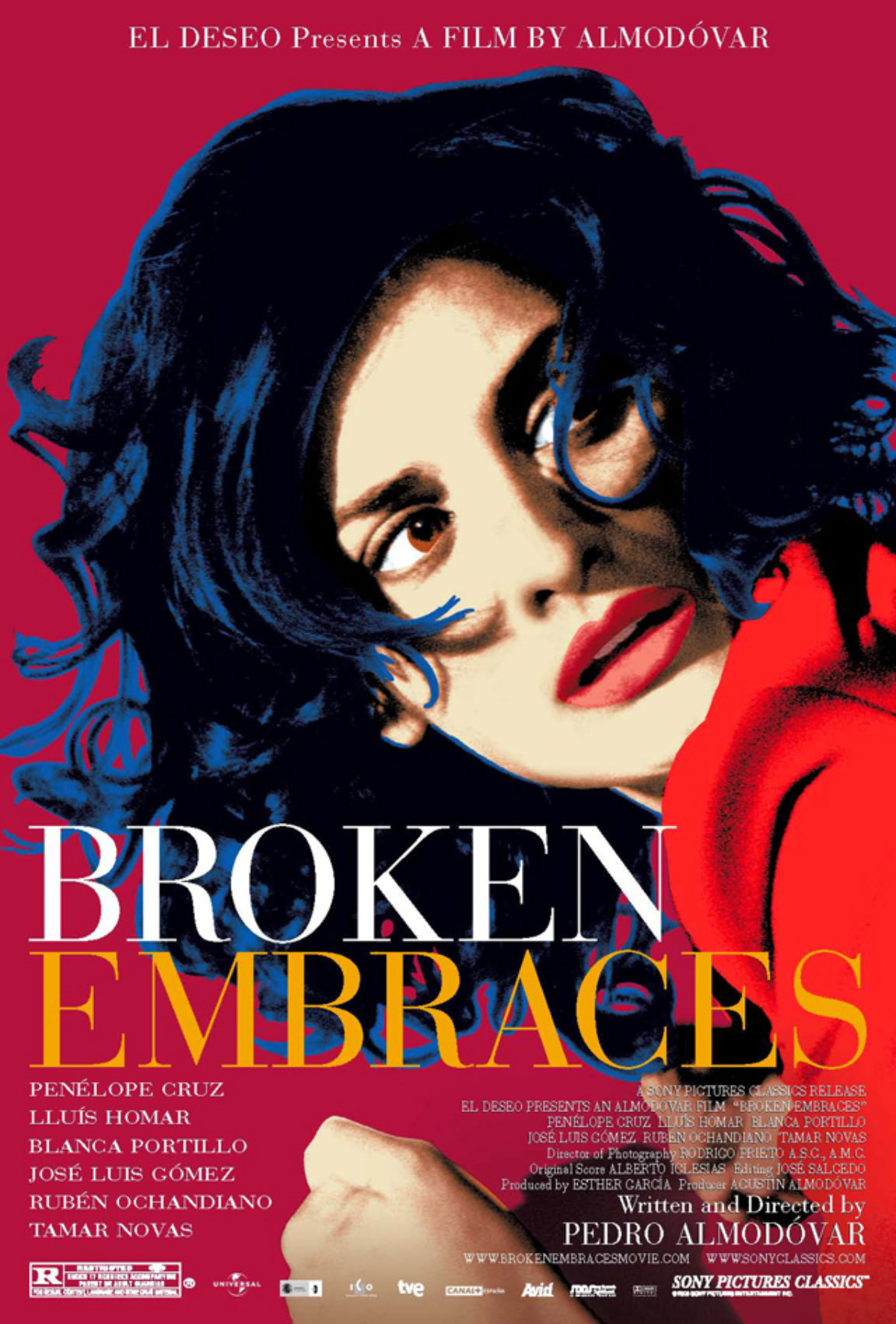

Mention must be made of red. Almodovar, who always favors bright primary colors, drenches this film in red: In the clothing, the decor, the lipstick, the artwork, the furnishings — everywhere he can. Red, the color of passion and blood. Never has he made a film more visually pulsating, and Almodovar is not shy.

Penelope Cruz has been Almodovar’s constant muse since “Live Flesh” (1997). Never has she been more clearly the brush he uses, the canvas he covers, and the subject of his painting. To see this film once is to experience his deliberate abandon. To see it twice, as I’ve been able to, is to understand that his style embodies his subject. That subject is: Film and life rush ahead so heedlessly that the frames are past before we can contemplate them.