Panahi, who is on camera almost constantly in “This Is Not a Film,” has a trustworthy face. He seems kind and philosophical — especially on this particular day, when he is awaiting a judge’s ruling on his appeal. Alone in a spacious high-rise apartment, except for his daughter’s pet iguana Igi, he has some flatbread and jam for his breakfast, calls his lawyer, is told Iranian judges almost never overturn sentences, but he might hope for a “discount” of the 20 years.

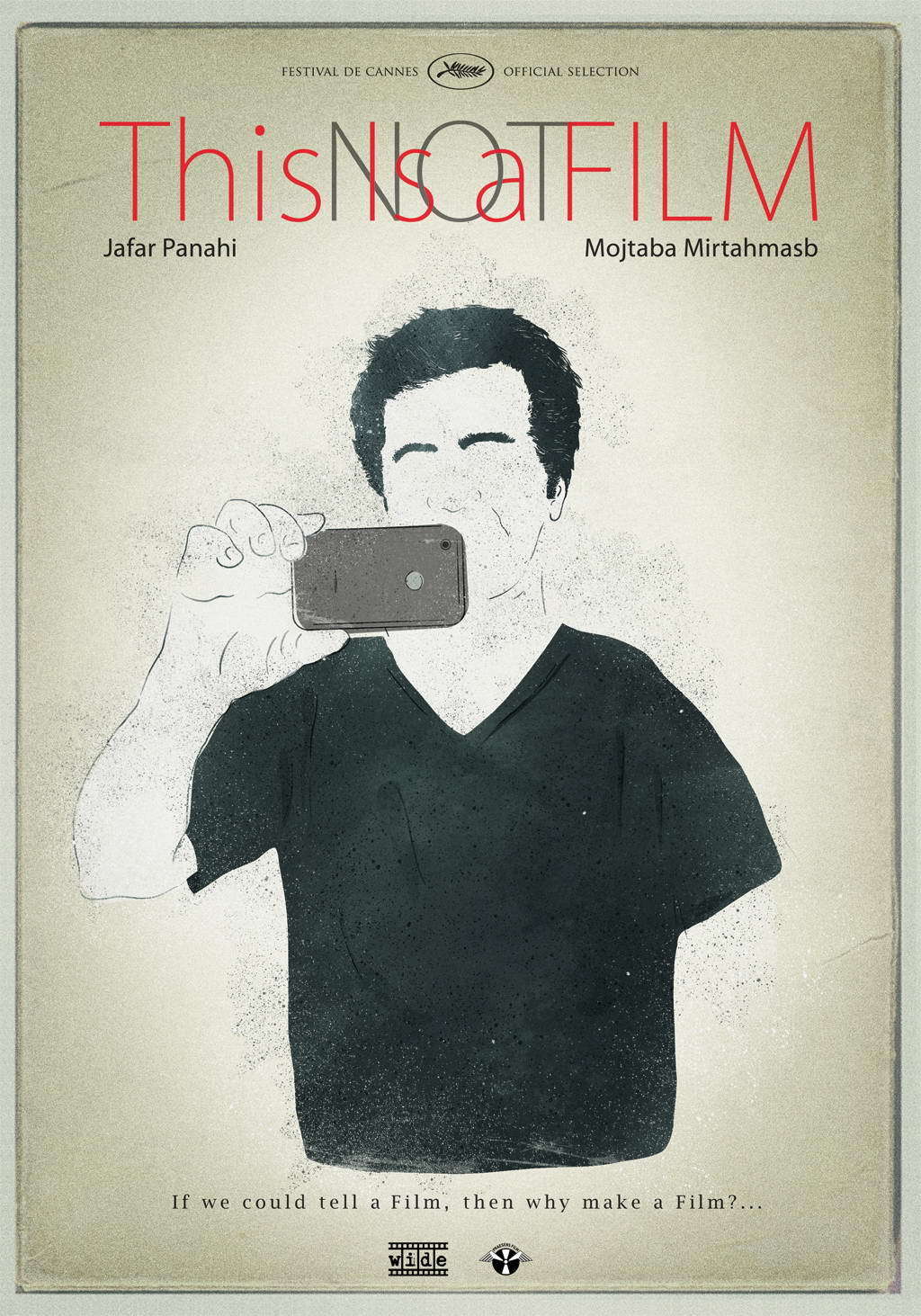

What comes next is an extraordinary act of courage. He has been filming himself, and now calls his friend Mojtaba Mirtahmasb to come over and join him. He’s not sure what to do. Forbidden to even say “action” or “cut,” Panahi wanders about the apartment, feeds the iguana, begins to describe the most recent screenplay he was forbidden permission to film, and comments on the DVDs of three of his films: “The White Balloon” (1995), “The Circle” (2000), and “Crimson Gold” (2003).

This man, who has been silenced, now finds things in the films he did not plan. In the first, the little girl who is playing his heroine, gets fed up with the process, tears off the cast she’s wearing for the scene and stalks out of camera range. “I’m not acting anymore!” she announces. The second is a drama about the difficulties of a group of women who attempt to move about the city without male companions (chaperones?). The third is about a large, stolid man who loses patience with himself. The actor is in fact schizophrenic (which the film doesn’t mention). He cannot take direction, but spontaneously he makes a gesture with his hands that expresses enormous frustration.

I’ve seen these films, and they are very good. They’ve won awards at many major festivals: Cannes, Venice, Berlin, and so on. I realize my description doesn’t begin to evoke the experience for you. That is precisely Panahi’s point. He demonstrates it in an agonizing scene where he begins to tell his friend the story of his banned film and uses tape on the carpet to mark out the floor plan of his heroine’s room. (She has been accepted by a university but forbidden by her father to attend, and locked in her room). He grows frustrated and tears up the tape.

Things happen. Carry-out food arrives. A neighbor drops off her dog for Panahi to watch, but the dog freaks out at the sight of the iguana. He watches the news on TV. It is Fireworks Wednesday, marking the Persian New Year, and in the evening, the city by tradition will be crowned by fireworks. Ahmadinejad has banned fireworks, murmuring darkly that they are in violation of Islamic law. The film never says the Islamic Republic shows great insecurity in the face of anything it doesn’t control. It doesn’t have to. I would like to show “This Is Not a Film” to those in the United States who are in favor of a close union of church and state.

There is nothing remotely political in Panahi’s films. But they can be read as parables. That is how Iranian directors must work these days. Even a domestic drama like last year’s Oscar-winning “A Separation” can be read in more than one way. And when religious fundamentalists are doing the interpretation, what chance does the human spirit have?

Little by little, detail by detail, “This Is Not a Film” leads to a final scene of overwhelming power. I don’t think it was even planned — no more than Panahi expected the little actress to take the cast off her arm. It simply happens, and then the film is over, having nothing more to say. Because, after all, it is not a film.