This weekend, legendary Australian filmmaker Peter Weir will finally receive a long-overdue statue from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in the form of an honorary lifetime achievement Oscar at this year’s Governors Awards. The 78-year-old Weir never won a competitive Oscar despite six career nominations—four for Best Director, one for Best Original Screenplay, and one for Best Picture—and he’ll be honored alongside songwriter Diane Warren, filmmaker Euzhan Palcy, and actor Michael J. Fox (who will be receiving the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award).

Weir made 14 feature films from 1974 to 2010, and not only are they all good (and most are great), but they’re also all of a piece with one another, wrestling with the same ideas and the same conflicts, telling beautifully nuanced variations of the same basic story.

All of Weir’s films, in one way or another, are about people who find themselves out of place and somewhere they don’t quite belong—geographically, sociologically, occupationally, ideologically—and the films then play out the consequences of that wrongness for both the protagonists and, perhaps more crucially, those they encounter. In some ways, the plots of Weir’s films could easily work as fish-out-of-water comedies, and in a few cases, they sort of have (as with “The Plumber,” “Green Card,” and “The Truman Show”). But in most cases, his films eschew the humor of being out of place and go straight for the jugular of deeply affecting human drama.

Despite the obvious thematic throughline in his work, Weir’s films marvelously adapt in tone and genre to the specifics of the story they’re telling. He’s made thrillers, dramas, mysteries, action epics, war films, survival stories, domestic dramas, black comedies, romantic comedies, and absurdist parables, and every last one of them has worked both on its own terms and as part of Weir’s authorship. At this moment of long-deserved Peter Weir celebration, here’s one take on his seven most essential films.

Light spoiler warning for movies that are between 12 and 47 years old.

“Picnic at Hanging Rock” (1975)

When Weir began making feature films in the 1970s he helped incite the Australian New Wave, which also launched the careers of George Miller, Bruce Beresford, Fred Schepisi, Gillian Armstrong, and Phillip Noyce (all of whom found significant success in Hollywood in the 1980s and beyond). Weir’s international breakthrough was 1975’s “Picnic at Hanging Rock,” about a few school girls going missing on a class trip to the famous Australian landmass, never to be seen again. In some ways it’s Weir’s most blatant deployment of his central theme: going to the wrong place not only has consequences, but you might also literally disappear off the face of the Earth. But “Picnic at Hanging Rock” isn’t really about the girls who go missing, nor is it really about subsequent efforts to find them. Rather, it’s about their classmates, who slowly come to grips (along with the film’s audience) with the complete lack of answers to a question that’s taken over their lives.

Weir’s two best ‘70s films—this and 1977’s “The Last Wave”—both employ elements of mysticism and defiantly refuse to resolve their central mysteries. “Picnic at Hanging Rock” is a bit like an Australian take on Michelangelo Antonioni’s “L’Avventura,” in that they both involve people who go missing on a trip and are never found. But while Antonioni used that device to comment on the ennui of the idle rich, Weir uses it to explore the loss of innocence for the young girls who never find out what happened. It’s Weir’s most ethereal film, with an intoxicatingly spooky flute score, and it’s very clearly influenced by Weir’s countryman, Nicholas Roeg, who first put Australian cinema on the map with 1971’s “Walkabout.”

“Gallipoli” (1981) and “The Year of Living Dangerously” (1982)

I sometimes think of Weir’s career as a series of seven double features, and nowhere is that more obvious than with these two. Both films star Mel Gibson, who at the time was only known for “Mad Max” (and long before he was known for all the things we now deservedly associate him with). Gibson’s performances in these two films illuminate one of Weir’s great talents: his ability to take actors known only for their work in action or comedy (like Gibson, Harrison Ford, Robin Williams, and Jim Carrey) and put them into everyman dramatic roles that audiences massively embraced. In both cases here, Gibson plays an Australian who travels to an Asian country in conflict because he thinks he can help, but in the end, he just ends up running to try and save his friend from being killed and arriving seconds too late.

“The Year of Living Dangerously” is the best kind of White Savior movie—one in which the white person slowly realizes they’re completely powerless to save anything, and in the end, they settle for barely even saving themselves. Gibson stars as an Aussie journalist in Indonesia during the country’s 1965 uprising, Sigourney Weaver plays a British embassy worker he falls in love with, and Linda Hunt deservedly won the Best Supporting Actress Oscar (the only acting-Oscar win for a Weir film) in a gender-swapped role as Gibson’s male colleague. Gibson and Weaver are just smoldering here; they’re almost disconcertingly beautiful, and the car seduction scene (set to a lovely piece of music by Vangelis) is some A+ sexy cinema.

And then there’s “Gallipoli,” maybe the purest distillation of Weir’s explorations into the consequences of being where one shouldn’t be. Gibson and Mark Lee star as two Australian lads who become mates as competitive sprinters, and then they enlist together to fight in WWI and are sent to Turkey. The two become involved in the Gallipoli Campaign that, well, you can look up how that went if you want to know what you’re in for. But fair warning, the perfectly constructed last five minutes of “Gallipoli” gets my vote as the most singularly devastating ending in film history.

“Witness” (1985)

Most of Weir’s films have been significant theatrical hits, though a few have been notable financial busts, like “The Mosquito Coast,” “Fearless,” and “The Way Back.” But three of Weir’s films became massive zeitgeist hits: “Dead Poets Society,” “The Truman Show,” and “Witness.” All three grossed well over $100 million at the box office (long before that was commonplace), and none of them were adapted from any existing IP or even based on true stories, which underscores just how unusual and spectacular their global success really was. They were just original dramas that connected with audiences in deep, universal ways.

“Witness” was the first film Weir made in America and it earned eight Oscar nominations, including Best Picture, Best Director, and Best Actor for Harrison Ford (the only nomination of his career). Ford plays John Book, a Philly homicide cop who hides out in Amish country to protect a boy who witnessed a police corruption murder and ends up falling in love with the boy’s mother (Kelly McGillis). “Witness” works on multiple levels—thriller, romance, cop movie, fish-out-of-water drama—and the craft work fires on all cylinders, especially the emotional score by Maurice Jarre and the Oscar-winning editing that beautifully takes its time with several nearly wordless sequences. But “Witness” is perhaps at its best as a gentle movie about the Amish, who are just as out of place in John Book’s world as he is in theirs.

“Fearless” (1993) and “The Truman Show” (1998)

Weir’s protagonists come from all over the map: students, lawyers, plumbers, athletes, soldiers, journalists, cops, inventors, teachers, botanists, waiters, architects, reality TV stars, ship captains, and gulag prisoners. Yet there’s a universality to all of their experiences that speaks profoundly to audiences. We all feel, at times, that we’re not where we’re supposed to be, and that consequences are afoot. At one point or another, Weir’s characters all end up looking at their situations and feeling some variation of, “This is not my beautiful house. Well, how did I get here?” Never is that more true than in these two ‘90s films, where the male protagonists even have a “This is not my beautiful wife” moment.

“Fearless” is unique among the Weir canon, in that the “wrong place” Jeff Bridges wrestles with isn’t communal, geographic, situational, or institutional. Rather, it’s the very status of being among the living. Bridges plays a plane crash survivor who begins to carelessly test his mortality in several ways, while also trying to help another survivor (Rosie Perez) cope with the loss of her baby in the crash. Perez deservedly received an Oscar nomination for her emotional performance, but it’s Bridges who really owns the film. He finds a sort of relaxed haphazardness in his acting, and takes us with him as he constantly switches between euphoria and despair.

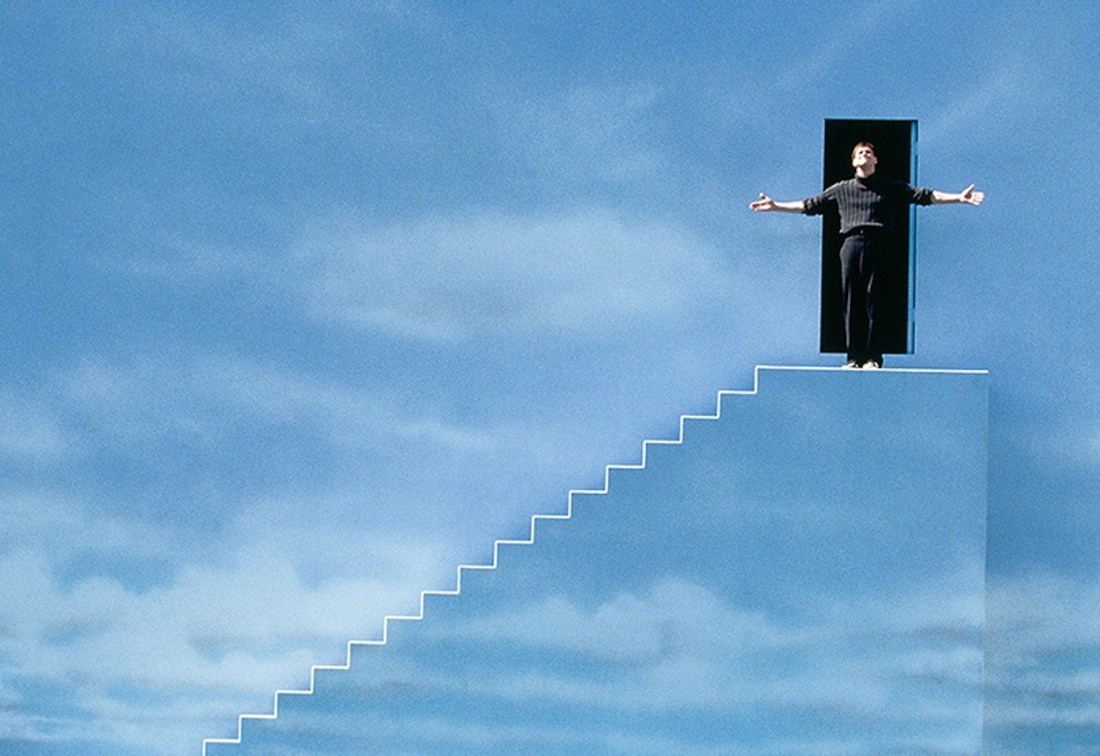

While “Fearless” is one of Weir’s criminally underseen hidden gems, “The Truman Show” is almost certainly his most famous and ubiquitous film, and the effortless construction of its artificial world rewards multiple rewatches. The script by Andrew Niccol (writer/director of “Gattaca”) is wonderfully economical, with every scene adding to a tapestry while being entertaining on its own. As he did with “Dead Poets Society,” Weir gave the lead role to the world’s most popular comedic actor at the time, but unlike Robin Williams in the former, here Jim Carrey was given leeway for improvisation, and he and Weir found the perfect balance between letting Carrey be Carrey while still keeping the material just dramatic enough to work with the film’s weightier issues. Nearly 25 years after its release, it remains shocking just how prescient “The Truman Show” feels about everything that’s happened with fame, media, and audience appetites in the 21st century.

“The Way Back” (2010)

Some will scoff at this choice over 2003’s “Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World,” and I freely admit “The Way Back” isn’t as great of a film on its own terms. But as the final movie of Peter Weir’s career, “The Way Back” is as beautiful a career capstone as cinema has ever seen.

Based on a true story, “The Way Back” is about a group of prisoners who escape from a Russian gulag during World War II and walk 4,000 miles through Siberia, the Gobi Desert, and the Himalayas until they find safety in India. While every other Weir film is about people in the wrong place, “The Way Back” chronicles the long, painstaking journey of getting to the right place. The film’s denouement, which involves a reunion (real or imagined) for the main character, feels almost like Weir putting his affairs in order. After four decades of making movies, and at the end of a film that dramatizes one of the most arduous journeys in modern human history, Weir finally gave his characters the ending they’d been so desperately seeking.