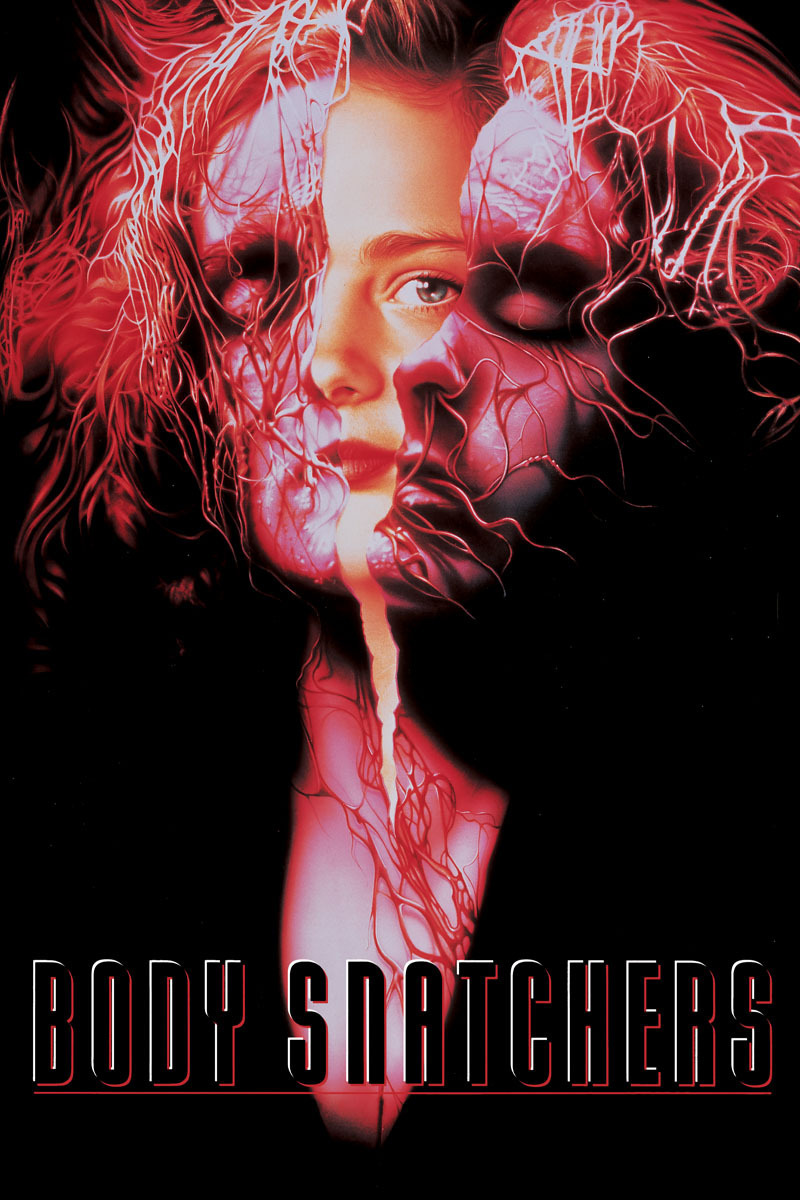

Sometimes I’ll be looking at someone I know, and a wave of uncertainty will sweep over me. I’ll see them in a cold, objective light: “Who is this person – really?” Everything I know about others is based on trust, on the assumption that a “person” is inside them, just as a person clearly seems to be inside me. But what if everybody else only looks normal? What if, inside, they’re something else altogether, and my world is a laboratory, and I am a specimen? These spells do not come often, nor do they stay long, nor do I take them seriously. But they reflect a shadowy feeling which many people have from time to time. And the classic story of the body snatchers taps into those fears at an elemental level. Since Jack Finney wrote his original novel in the 1940s, his vision of Pod People has been filmed three times: In 1954 and 1978 as “Invasion of the Body Snatchers,” by Don Siegel and Philip Kaufman, and now simply as “Body Snatchers,” by Abel Ferrara. The first film fed on the paranoia of McCarthyism. The second film seemed to signal the end of the flower people and the dawn of the Me Generation. And this one? Maybe fear of AIDS is the engine.

Ferrara’s version is set on an Army base in the South, and told through the eyes of a teenage girl named Marti (Gabrielle Anwar) who has moved there with her family. Her dad (Terry Kinney) is a consultant. She doesn’t get along well with her stepmother (Meg Tilly), although she likes her stepbrother (Reilly Murphy). Before the family even arrives on the base, Marti has been grabbed by a runaway soldier in a gas station rest room, who shakes her and says: “They’re out there!” And they are. It gradually becomes clear that visitors from outer space have arrived near the army base, unloading pods that they store in a nearby swamp. The pods sent out tentacles toward sleeping humans, the tendrils snaking up into noses and ears and open mouths and somehow draining out the life force, while the pod swells into a perfect replica of the person being devoured. When the process is complete, the leftover body is a shell, and the new pod person looks and sounds just like someone you know and trust.

There is a catch. They don’t look quite right around the eyes.

And they don’t seem to possess ordinary human emotions, like jealousy. Their goal is to occupy the human race, rent-free. And, of course, once Marti understands what is happening, she can’t get anyone to believe her.

Ferrara, a talented but uneven director, is capable of making one of the best films of the year (“Bad Lieutenant,” 1992) and one of the worse (“Dangerous Game,” 1993). Here, working in a genre unfamiliar to him, he finds the right note in scene after scene.

There is horror here – especially in the gruesome scenes that show us exactly how the pods go about their sneaky business – but there is also ordinary human emotion, as Marti and her boyfriend deal with the fact that people are changing into pods all around them.

Ferrara and his writers are also clever in placing the body snatching story in the middle of a pre-existing family crisis. Marti and her stepmother do not get along, and there is a sense in which the teenage girl already feels that her “real” mother has been usurped by an impostor, and her father subverted. Even her little brother is an enigma: She likes him, but resents having to share love and space with him. So if some of these people turn out to be pods, the psychological basis for her revulsion has already been established.

Ferrara’s key scenes mostly take place at night, on the Army base, where most of the other people are already podlike in their similar uniforms, language and behavior. There is a crafty connection made between the Army’s code of rigid conformity, and the behavior of the pod people, who seem like a logical extension of the same code.

Most important, for a horror film, there are scenes of genuine terror. One shot in particular, involving a helicopter, is as scary as anything in “The Exorcist” or “Silence of the Lambs.” And the fright is generated, not by the tired old slasher trick of having someone jump out of the screen, but by the careful establishing of situations in which we fear, and then our fears are confirmed.

“Body Snatchers” had its world premiere last May in the official competition of the Cannes Film Festival, where the outspoken Ferrara did not endear himself by claiming that Jane Campion’s “The Piano” was such a favorite “the jury gave her the award when she got off the plane.” Certainly “Body Snatchers” is not the kind of movie that wins festivals: It is a hard-boiled entry in a disreputable genre.

But as sheer moviemaking, it is skilled and knowing, and deserves the highest praaise you can give a horror film: It works.