The Final Girl needs no introduction, but here’s one anyway: she’ll get what she wants, if she’s holding the knife. Horror movies started relying on intrepid, doe-eyed Final Girls to round out their posters long before Professor Carol J. Clover defined them as “female victim-[heroes]” in her influential 1987 essay “Her Body, Himself :Gender in the Slasher Film.” Now, decades later, movies let female protagonists toss around guns and glossy hair with more confidence than they used to, but they require these capable knockouts to slip back into the Final Girl’s worn-out shoes by the last half hour.

Movies have kept their cold grip around the old Final Girl, in part, because they’ve been egged on by feminist fandoms surrounding classic horror Final Girls like “The Texas Chain Saw Massacre”’s petrified Sally Hardesty (Marilyn Burns) and “Halloween”’s gob-smacked Laurie Strode (Jamie Lee Curtis), but the Final Girl isn’t necessarily a precedent to be proud of. It might even be time to give her up.

When “Texas Chain Saw” released in 1974, critics were less inspired by Sally’s hardiness as they were shocked that she “screams endlessly,” as Roger Ebert wrote at the time. The film, which Clover establishes as the primeval petri dish for Final Girls, does not assign any obvious value to Sally’s womanhood, aside from her being, like a white cross in the dirt, standing at the end of everything. “Texas” simply sets the standard for what later slashers like “Halloween,” “Friday the 13th,” and “The Slumber Party Massacre” expand on—the Final Girl is the “girl scout, the bookworm, the mechanic,” writes Clover. “She is always smaller and weaker than the killer,” though “she grapples with him energetically and convincingly.”

Clover establishes the Final Girl as a product of a film industry that reduces and constrains women of all kinds—bitches and Barbies, those who can’t find the will to fight back, and those who kill. The Final Girls’ womanhood was initially presented as incidental, so viewers could digest it superficially. In 1984’s “A Nightmare on Elm Street,” Nancy (Heather Langenkamp) barely blinks while setting Freddy Krueger’s rotten body on fire, but The New York Times critic Vincent Canby nonetheless trivializes her as “pretty and bouncy enough to be a terrific cheerleader” in his review. To some audience members, these early Final Girls, often written and appraised by men, were more effective pieces of eye-candy than inspiration. But then Clover’s essay came out, and movies became more self-aware.

“Only virgins can [outsmart the killer],” Randy instructs while holding a beer in 1996’s “Scream.” “Don’t you know the rules?” At this point in horror history, audiences understood that the exhausted girl at the end of movies like “Alien,” “The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2,” and “Leprechaun” had a name. This made it easier for women to identify with her, and, by the 2000s, feminists incorporated lone-wolf beauties like Buffy into their larger mission of claiming “femininity as a source of power,” says Irene Karras’ 2002 academic article about “Buffy the Vampire Slayer.”

Our modern Final Girl springs from this ethos like Venus in the half shell. The rise of sardonic, socially-intelligent horror movies in the 2010s reworked the trope into a real girl’s Final Girl, making her sexually confident (Tree from “Happy Death Day,” Jay from “It Follows”), morally ambiguous (Needy from “Jennifer’s Body,” Dani from “Midsommar”), but still fated to survive (Dana from “The Cabin in the Woods,” Max from “The Final Girls”).

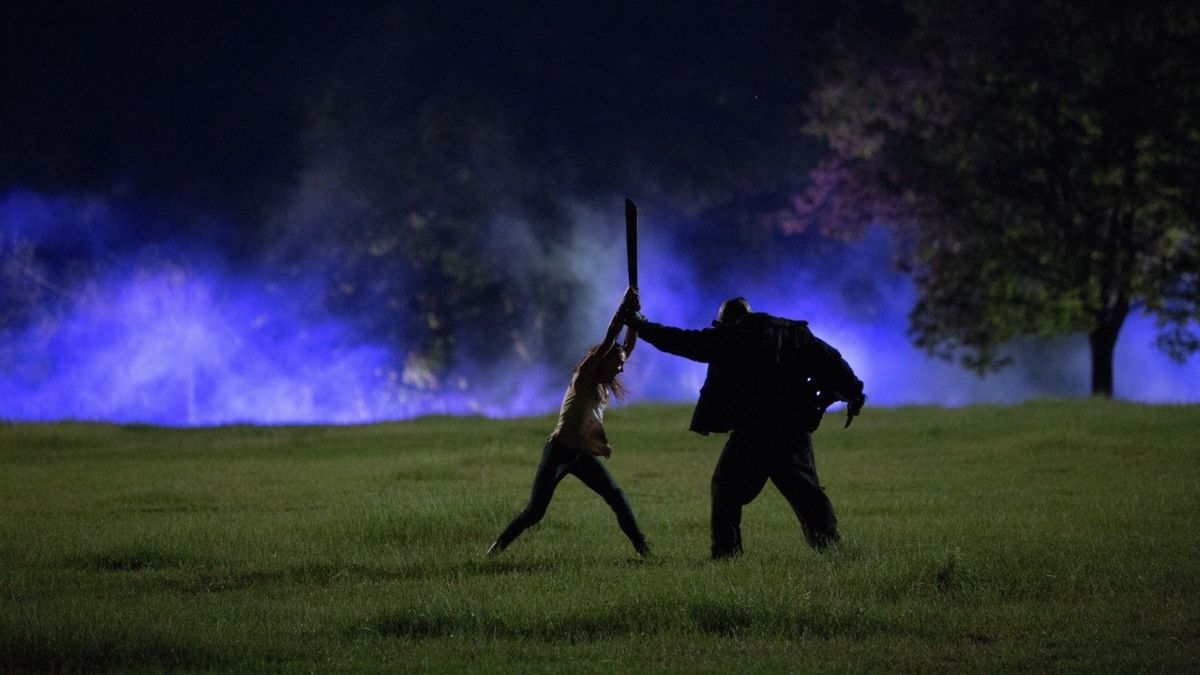

This new Final Girl is less prone to interminable shrieking than “Texas Chain Saw”’s Sally, and she’s adept at swallowing her disgust. Maxine in the 2022 sexploitation film “X” backs a truck up over horny, homicidal grandma Pearl without hesitation, and barely reacts when she feels Pearl’s head rupture like a pea under the tires. Sam in 2023’s “Scream VI” is amused to end her assailant, electing to put on the series’ moaning Ghostface killer mask before knifing open his neck, chest, and stomach.

The new Final Girl is also ostentatious, not a trembling babysitter. Maren in 2022’s “Bones and All” and Julia in 2016’s “Raw” both eat warm chunks of their boyfriends’ flesh, smearing their mouths with his foreign blood, a transgressive act of love for both Final Girlhood (the traditional Final Girl is covered either in critical wounds, or the blood of the expulsive killer), and under most social codes.

But though the Final Girl has grown into a multifaceted woman—a woman who is, regressively, typically slender and white, with a 1974 angel’s face—she is still a mutilated victim. Crowning her as your personal feminist hero means taking, with some religious satisfaction, wafers of suffering into yourself.

Fourth wave feminism is punctured by an overreliance on this victimhood. True crime, which dominates podcast topics and seemingly Netflix documentaries, mostly services women, who make up something like 80% of its audience. “The interest in the subject comes from women’s awareness that they are the victims of a vast majority of interpersonal violent crime,” University at Buffalo professor David Schmid told CNBC in 2023 in an article describing how some women are so soothed by serial killer narratives that they use them to fall asleep. Other women create Pinterest boards and how-to YouTube guides dedicated to dressing like female protagonists in horror video games (lace camisole, lace-up boots, a skirt that ends at the thigh) and putting makeup on like a Final Girl (concealer, swipe of mascara, peach lipstick to accentuate your cries).

Supposedly, this is all in service of female empowerment. We should equate ourselves with Final Girls, and missing girls, and dead ones, too, so that we can better understand the circumstances that brought them there—the, we assume, men with twisted needs that stalk, harass, and take them from their pleasant beds.

“When something horrible happens in reality, whether it be war or kidnapping or murder or assault or any of those things,” horror director Jen Soska told The Cut in 2016, “there’s unfortunately no censorship. When you watch a movie, you can deal with those issues. You can come as close as you can to experiencing what the characters are experiencing from the safety of your own seat.”

But, as comfortable as I am in my seat, I don’t want to relate to the Final Girl anymore. Or, I don’t want to relate only to the Final Girl, someone who is contracted by her role to navigate her pain alone, with limited vulnerability. She is an admirable force, she who transcends masculinity and femininity—physically intimidating, like a Rodin sculpture, and lovely like a Renoir flower—but she is alone. To a female audience member, the Final Girl acts as an everywoman, but, on-screen, she is separate and above the rest of womankind. She doesn’t know empowerment as much as she understands isolation.

I’m ready for films to take on more varied horror stories. Multiplayer horror games like “Dead by Daylight,” or ensemble-led TV shows like “Search Party” are already exploring them through their necessity for multiple survivors, which allow for more elaborate narratives, gender dynamics, and outcomes.

Horror movies, on the other hand, have been placing solo female protagonists on a rotating conveyor belt for too long, releasing the same kind of character for the same lonely narrative: though, as a woman, you might contain critical poise and power, you will inevitably experience unique pain. So shut yourself down. Close yourself up. Become hardened to the world.

While the Final Girl’s personality has expanded in intriguing ways, her European looks and usually boyish name (Jay, Max, Sam, etc.) mire her in an outdated expectation that, to be a successful woman, you have to be unlike all the other, more bumbling ones. And, even so, the Final Girl is only ever in community with other victims—agony is what ties her to every character in her movie.

It’s getting boring. I don’t want “femininity” to always mean “fear.” I think horror movies should relinquish the Final Girl for her own sake.

Women, like everyone else, deserve moments of kinship and security, or even more fragile feelings like weakness and fatigue, without worrying that indulging in them will turn them into prey. Being prey, even a gorgeous doe camouflaged by peach lipstick, doesn’t leave enough room to be human. Powerlessness looks good on movie theater screens, I recognize, but we’re so much more than powerless.