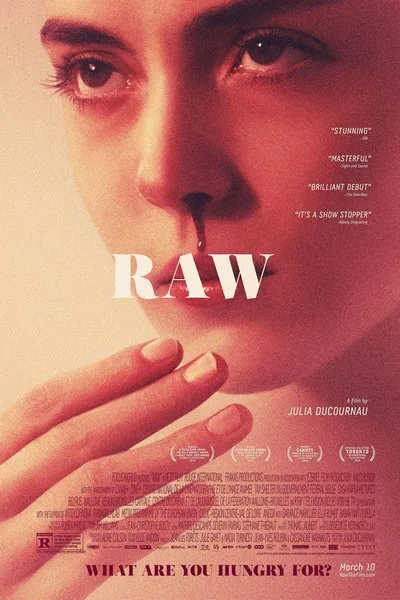

On International Women’s Day, it seems only fitting to write a review of “Raw,” a horror film about a brilliant but innocent teenage girl who finally lets loose and asserts her true identity as a cannibal.

It may not sound like it on the surface, but “Raw” is absolutely a celebration of female power—of realizing who you are, what you want and how to go after it, albeit with brutally bloody results. And it comes from the mind of another young, brilliant woman, French writer/director Julia Ducournau, making her wildly assured feature debut.

Ducournau’s lurid, vivid film is visually striking, full of images that will shock you while others will lull you with a hypnotic beauty. And though it has glimmers of style that are reminiscent of thriller masters—the body horror of David Cronenberg, the gaudy surrealism of David Lynch—“Raw” is very much its own artful entity with its own singular voice.

“Raw” will make you curl up in a ball in your seat, daring to watch through splayed fingers—and not necessarily in response to the film’s violence. Ducournau pinpoints and expertly depicts the frights that exist in the everyday world—especially when you’re a young woman trying to figure out your place within it. That’s what’s so startling about the film: It’s not necessarily the monstrous moments that’ll shake you up, but rather the mundane ones.

Having said that, it’s exciting to see a female filmmaker establishing herself so forcefully in what traditionally has been a male-dominated genre. And she’s only 33 years old. (The recent “XX,” which consisted of four horror shorts by and about women, also entered this territory, but with frustratingly inconsistent results.) Ducournau mixes it up visually with a combination of eerily austere establishing shots and long, fluid camera movements. She knows when to hold back to create suspense and when to unleash the full fury of her grisly imagery.

With the help of cinematographer Ruben Impens’ beautifully nightmarish use of color and light and Jim Williams’ chilling score, Ducournau creates a lingering sense of mystery throughout: How much of this is a hallucination? Could what we’re watching possibly be real?

“Raw” begins on a note of understated tension as 16-year-old Justine (Garance Marillier with a thrilling, daring performance in her first major role) travels to veterinary school with her parents, where they both studied and where her brash older sister, Alexia (Ella Rumpf), is currently a student. This is a prestigious institution, but the campus itself is especially bleak and unwelcoming; during the rare instances when these aspiring doctors get to go outside, the skies always seem to be cloudy. It’s an unusual and unsettling location for a film.

Everyone in Justine’s family is not only a veterinarian but also a strict vegetarian, a lifestyle choice she finds difficult to adhere to when confronted with a series of raucous and sadistic freshman hazing rituals. In one of them, the older students force her and her classmates each to eat a small piece of raw rabbit kidney. She’s initially resistant and repulsed, as anyone would be. But soon enough, she finds that the tiny nibble of animal flesh stirs something primal in her—a hunger she never realized was there. In no time, Justine is sitting in front of the refrigerator in her dorm room in the middle of the night, tearing into a raw chicken breast to the bewilderment of her flirty, gay roommate and only friend, Adrien (Rabah Nait Oufella). The look in her eyes lets us know that this won’t be nearly enough to satisfy her.

Ducournau cleverly takes her time in these moments as she slowly reveals each shocking step in Justine’s carnivorous evolution. She never judges this character, even as her choices have increasingly harmful consequences. Rather, she seems fascinated by Justine, watching both from afar and up close as she morphs from shy little girl to sly huntress.

Clearly, the physical seizing of flesh is a metaphor for a sexual awakening, but the transformation Justine undergoes in “Raw” could be interpreted in a variety of ways. Justine is a little awkward as she gets gussied up, goes to parties and flirts with boys. An attempt at bikini waxing goes horribly wrong in the film’s most squirm-inducing scene. She clearly has no idea what she’s doing, and that insecurity gives her character—and the film as a whole—an unexpected element of relatability.

But as Justine gives into her yearnings in a way that’s drastically opposed to the philosophy under which she was raised, she becomes more brazen, yet also more confident and powerful in her femininity. Somewhere, beneath the blood, she might even be happy—entranced by her newfound lust for life. It’s like a drug. And it’s clearly habit-forming.