Dušan Makavejev was 83 when he finally succumbed to years of health problems at his home in Belgrade, Serbia. Along with Jean-Luc Godard, Ken Loach, Lindsay Anderson, Jacques Rivette, Miloš Forman, Chantal Akerman and other directors of his generation, he helped set the agenda for political European art cinema in the late 1960s and early 1970s. His work played major festivals in Chicago, Cannes, Berlin, Mar Del Plata, and Telluride, among others, and sometimes picked up prizes. His features “Sweet Movie” and “W.R. Mysteries of the Organism” are available from the Criterion Collection, who also put out a no-frills set of his 1960s feature films that’s as good a place as any to start diving into his rich body of work. He didn’t direct many features, but the few he did revealed much about his artistic inner life, the history of his home country, and the direction in which thought labor, sexual politics, and art funding were all headed.

If you’ve read anything about Makavejev, you’re likely familiar with his quote “Narrative structure is prison; it is tradition; it is a lie…” which is catchy, certainly, but also more telling than it appears. The filmmaker, author and teacher was raised in Belgrade when it was part of Yugoslavia, and though he studied psychology, it was film that he used as a ladder to climb those prison walls. He believed tradition—and not just cinematic tradition—was used to cage people in ways of life that kept them blindly productive and subservient to a violent state apparatus. He saw the way his country feted the strong and erased the weak and he said something about it, throwing him into lifelong battle with his homeland. He escaped his own prison, but refused to leave others to their fate simply because they weren’t artists with the power to say what they believed. He wanted something better for those with no voice, and so he spoke on their behalf, putting himself in danger in the process. He knew not everyone could see the bars.

His filmmaking career started in 1954, when the famous archivist and cineaste Henri Langlois brought a collection of films to Belgrade and shared them with the members of Kino Klub, a local collective that Makavejev belonged to. Makavejev had grown up with Russian and European social realism, the preferred film language handed to directors by repressive leaders, as well as silent comedy shorts and Disney cartoons, which could be screened in then-Yugloslavia without fear of stoking the dormant revolutionary spirit. Watching films by Jean Vigo and Rene Clair for the first time, the young Makavejev saw a world of expressive potential and anarchic grammar. He realized that film could be playful, fun, and angry at the same time. After mainlining the poetry and pop provocations of French cinema, he picked up a camera to make the short film “The Seal,” which he released the following year. He soon became a target of censors and the slavic authorities that he attacked in his early films—subtly at first, then overtly.

His second short was “Anthony’s Broken Mirror,” in which a young man encounters a department store mannequin that comes to life when he looks at her, then kills a rabbit and shatters a window to impress and claim her. The dream of romantic love is presented as a barrier than cannot be shattered. There is no better existence on the other side, just a broken model for commodities and complacency. His mad gestures of love turn tragic and twisted, as he buries the young rabbit while a crowd watches, then stares in shame at the pile of limbs where the mannequin once stood after he ‘frees’ her. His 1958 short “Don’t Believe in Monuments” is a rhyme with “Broken Mirror.” A young woman in a park drapes herself around a statue and begins teasing it erotically, rubbing her foot on its chin, licking its ear, rubbing its nipple, before a terrible realization illuminates her features. She checks for a pulse, pounds its bronze chest and sees that this man of stone is in fact dead. The great strong man, the symbol of superiority and accomplishment she so loves, cannot love her back.

Authorities were not amused. “Don’t Believe in Monuments” was banned throughout the country, supposedly for its vision of languorous eroticism but possibly because the government saw in the film what Makavejev was saying without words: authoritarian power would vanish if the people agreed to stop propping it up. He was undeterred by the setback, working tirelessly on short-form films and writing plays all throughout the early 1960s.

In 1965 he spread his wings and made his first feature, “Man is not a Bird,” a delirious, essayistic whatsit. The film depicts the bifurcated sexually tinged escapades of two different classes of working man, a miner and an engineer, both having romantic difficulties. The title comes from an amusing vignette where a mesmerist makes members of his audience pretend they are animals. The state pulls its strings and an implanted ambition plagues them, keeping them blind to the horrid working conditions in which they toil. Both the engineer and the miner are tools of the state, and a far cry from the statue in the park so beloved by the young woman in “Don’t Believe in Monuments.”

“Man is Not a Bird” was a new kind of movie, and a foundational text of the Open Cinema movement of the 1960s, when filmmaking technology became available to non-state funded artists, and the Black Wave, Yugoslavia’s version of the French New Wave—a school of angry young artists from the Balkans, many of whom benefited from the decentralization of filmmaking equipment and funding. The movie is distinguished by its free floating narrative, many tangents, mixture of fact and fiction, and freewheeling experimental editing strategies. That style became Makavejev’s trademark, which makes the title seem like a bit of an ironic declaration: at any moment, his films could change into something else.

Then came “Love Affair, or the Case of the Missing Switchboard Operator,” in which a woman’s yearning for sexual autonomy leads her to destruction at the hands of unfeeling men who lust after her. The investigation into the lead character’s death is interspersed with her progressing story and the ways in which crime is investigated by the Yugoslavian state provide an eerie counterpoint to her romances. His next feature, 1968’s “Innocence Unprotected,” was even more bold, cross-cutting the first Yugoslavian talkie, a vehicle for Yugoslavian athlete and bodybuilder Dragoljub Aleksic, with images of the war-ravaged streets over which the strongman once soared. Aleksic’s death-defying stunts, hanging by his teeth from great heights or riding a unicycle between houses on a tight rope, betrayed a broken promise to the people that men like this would keep them safe, that they were being protected.

By now the Yugoslavian authorities had Makavejev’s number, and were not about to let him continue criticizing the state. He’d become an international sensation by this point, having won major awards at the Berlin Film Festival and then been brought back to judge it in 1970, making history when the festival shut down over a dispute he was involved in. Jury president and WWII veteran George Stevens hated one of that year’s festival entries, Michael Verhoeven’s brutal and bleak Vietnam War film “o.k.” (fans of Brian De Palma’s “Casualties of War,” a film about the same incident, will know why it was controversial). He thought it was anti-American and obscene, and he did want it screened. Makavejev demanded it be shown, and the standoff between them led the festival to be cancelled, the only time in the history of the Berlin Film Festival that no prizes were given.

Infuriated, Makavejev went home and directed the film for which he is still best remembered, “W.R. Mysteries of the Organism,” which contains his signature blend of highly charged metaphorical fiction and non-fiction with a more traditional story. Wilhelm Reich’s theories of sexual gratification are the glue that holds the kaleidoscopic film together. His ideas, including his most famous notions about the importance of orgasm in human health, made him deeply unpopular in Europe. He spent much of the rest of his life resettling in different countries, looking for a home where he could live and work without interruption or persecution.

He never quite succeeded. It should perhaps have been expected that the same fate would befall Makavejev, whose film on Reich (and the unhealthy suppression of sexuality) got him banned from Yugoslavia for almost two decades. The film turns Stalinism, and the false representations of communism that result after the break-up of the Soviet Union, into a metonym for unhealthy psychology and sexual behavior. The usual Makavejevian superman (represented by a Russian figure skater) is depicted as someone so repressed that consensual sex causes him to go mad and murder the woman he beds. The final image, of her decapitated head singing to camera, is one of his most endearingly haunted images, an example of the tonal tightrope that he unicycled across.

After the part-rapturous, part-horrified reception to “WR,” he drifted around the world. He made his best film, 1974’s “Sweet Movie,” with a budget cobbled together Canada and several European countries. About a beauty queen violated by many versions of masculinity and male authority, it shows the sense of dislocation and homesickness that Makavejev suffered during his wanderings abroad. He cared deeply about his homeland but was prevented from passing film through a camera on its soil. Featuring ethereal photography by Pierre Lhomme’, “Sweet Movie,” like all his works, is thematically fearless and texturally omnivorous: a rootless communist sprite seducing and murdering children here, black and white news reel footage of bodies recovered from the Katyn Massacre in Poland there.

“Sweet Movie” caused just as much of a stir as “W.R.” It was banned in many countries, its own stars disowned it, and made very little money during its short theatrical run. Its heretical images of sexuality and violence made it many enemies with censorship boards abroad. Not even endorsements from the likes of beloved provocateur Pier Paolo Pasolini made a difference.

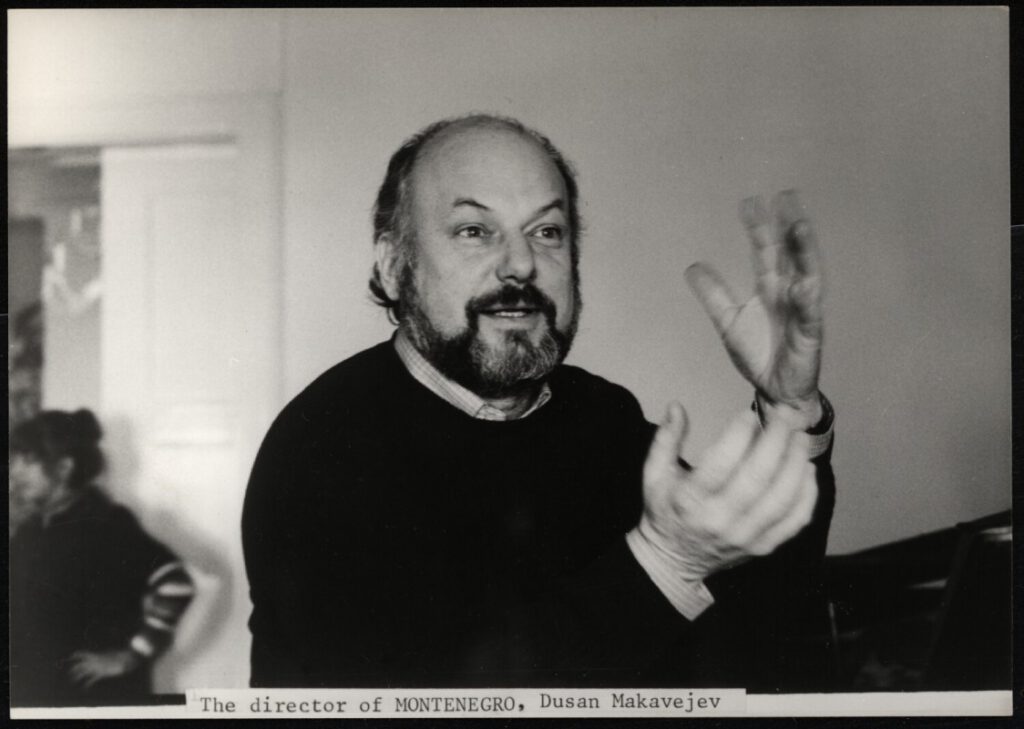

in the late ’70s and into the ’80s, Makavejev made short form work for festivals and eccentric backers, then returned to fiction features, releasing “Montenegro,” about an interloper in a gypsy commune; “The Coca-Cola Kid,” a Marxist study of a boyish American sales rep sent to Australia to wreck them with industry; and “Manifesto,” a bedroom farce about a king’s impending arrival in a tiny European village. This trio of filmsblunted the scalpel he usually used to dissect the political self and authority. They were less scattered and formal, more approachable. They are beautiful films all, heartfelt and charming and romantic, though you could mistake them for the work of a less ferocious mind than Makavejev’s if you did not know they were his.

His final works, the military comedy “Gorilla Bathes at Noon” and the documentary road movie “A Hole in the Soul,” find Makavejev in a reflective mood. He appears on camera for the bulk of “A Hole in the Soul,” musing about his life and his home country, to which he had finally returned. He’d travel, teaching at Harvard and lecturing when given the chance, but his heart was always in a broken country. By the time he was able to work in his home country again, it had vanished. Yugoslavia had splintered into different territories, and decades of conflict and tribunals raged on after Makavejev retired.

He had said what he could, and as he looked around in his old age, he must have seen that there were too many problems to be combatted through his uncynical, lustful, joyous art. Funding had never come easily to his productions, and during the last two decades of his life, as he aged and became less of a sure thing for insurers and producers alike, he stopped making movies. I’ll forever be jealous of the people who got to see him speak in classrooms, who worked with him, who heard his marvelous laugh in person. Through his art, it becomes easy to feel as though you know him—or his mind, always racing, always excited to see how each new word, symbol and image solidifies an argument for the people. He spent the best years of his life trying to show us that freedom was just on the other side of what we’re told, that myths and traditions can blind us to the best parts of ourselves, and that if we allow ourselves to truly see, to love ourselves and each other, ecstatically, passionately, even grotesquely, the bars will vanish, the prison will fall, and the lie will never be told again.