After making two experimental shorts (1969’s “Stereo” and 1970’s “Crimes of the Future”), Canadian filmmaker David Cronenberg decided back in the early ’70s to boost his profile with a more overtly commercial project. Like many filmmakers, both before and since, he figured the best way to do this was by making a low-budget exploitation film—come up with a lurid concept and a catchy title (not necessarily in that order), throw in some sex and violence to keep the audiences satisfied and make it so cheaply that it will clear enough of a profit to make financing the next project a little easier. The resulting film “Shivers” abided by those parameters, but not in the ways anyone could have expected. When it did finally explode off of movie screens in the fall of 1975, it proved to shock anyone who encountered it, even inspiring debate about its artistic worth on the floor of Canada’s Parliament, while simultaneously becoming the most profitable Canadian film ever made up until that point.

As one can plainly see from the film’s long-overdue Blu-ray debut from Lionsgate, for all of its technical crudity and questionable performances on display, “Shivers” is a work that fits in easily with the rest of Cronenberg’s subsequent oeuvre. It’s an audacious combination of intelligent and psychologically-nuanced storytelling that turns all forms of genre convention on its head, and is filled with jet-black humor and grisly visuals designed to bend the mind and churn the stomach in equal measure. In fact, not only has “Shivers” not dated in any aspect other than the most obvious surface details (hairstyles, clothes, decor), its barbed attack on most all basic mores is as gleefully offensive, in the best possible way, as it must have been to those who saw it for the first time 45 years ago, though even those people would have had no idea of just how prescient it would prove to be.

The film opens with an extended advertisement touting the benefits of Starliner Towers, the state-of-the-art apartment complex where virtually all of the subsequent action will unfold. Antiseptic in design and suffused with every technological advancement and accoutrement one could imagine, the place is like the architectural equivalent of one of those old Dewar’s Profile ads and you can practically see a copy of the current issue of Playboy sitting in full view on a coffee table in every single unit. While a young couple is meeting with the building’s manager (Ron Mlodzik) downstairs to sign a lease, something decidedly unsavory is going on upstairs. We then see a middle-aged man breaking into an apartment, beating and strangling the teenaged girl inside and then doing something particularly nasty to her body with a scalpel and a bottle of acid before slitting his own throat.

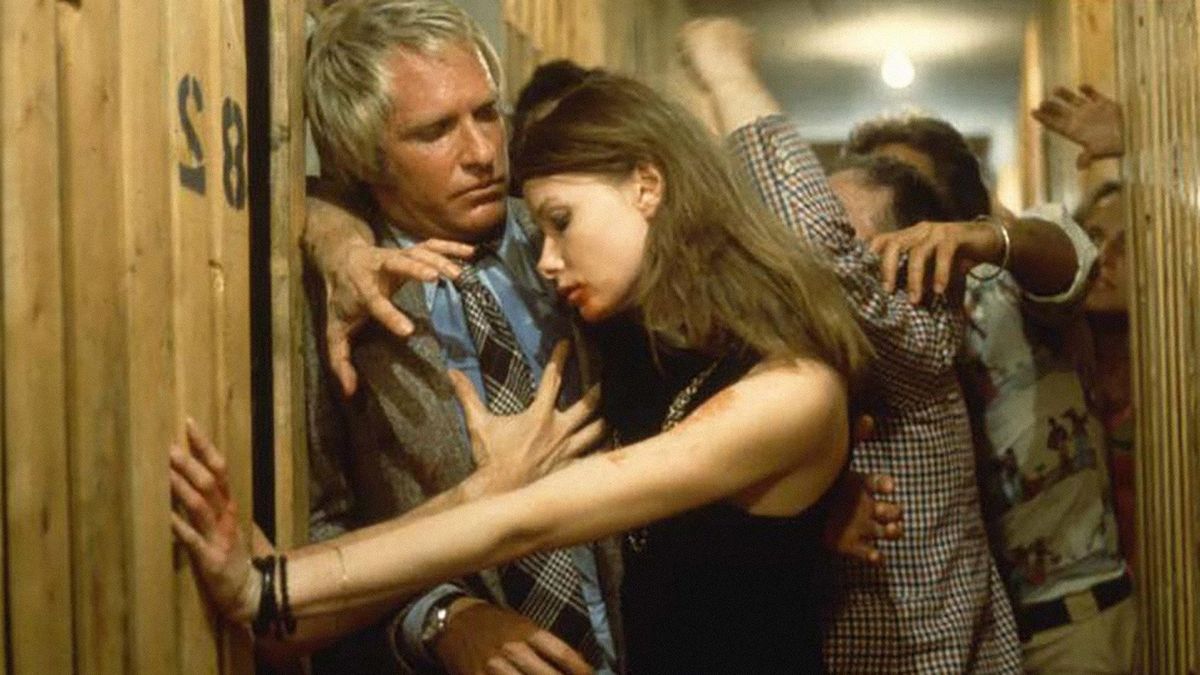

When the bodies are discovered, Roger St. Luc (Paul Hampton) is surprised to discover that the dead man is Dr. Emilie Hobbes, one of his former medical professors. Curious, he looks up Hobbes’ business associate, Rollo Linsky (Joe Silver) and learns that the two had been working on devising a new breed of parasite that could replace failed organs in the human body. As it is eventually revealed, Hobbes actually devised a parasite that was essentially part aphrodisiac and part social disease. He believed it would help mankind get more in touch with their basic primal feelings and he used Annabelle, who was his mistress, as an incubator. Unfortunately, Annabelle was also sleeping with several other residents and before long, the parasite has begun spreading throughout the building—in the most infamous example, one woman (the inimitable Barbara Steele) is taking a bath when the creature, unbeknownst to her, crawls up the drain and you can take it from there. Before long, the building is overrun with degenerate sex fiends attacking the rapidly decreasing numbers of the uninfected and while St. Luc, Linsky, and Forsythe (Lynn Lowry), St. Luc’s lovelorn nurse, try to find a possible antidote at first, the focus soon shifts to trying to escape before all is lost. You probably do not need to guess as to how well that turns out.

Oh yeah—if you are planning some kind of dinner-and-a-movie thing one night, this might not be the ideal selection for the movie portion of the evening.

A lot of you may not have seen “Shivers” as of yet but if you do watch it now, you will almost certainly be going into it with some kind of working knowledge of the cinema of Cronenberg. You will know that many of his films, especially his early run of projects that included such cult favorites as “Rabid” (1977), “The Brood” (1979), “Scanners” (1981), “Videodrome” (1983) and his mainstream breakthrough “The Fly” (1986), have dealt with the increasingly visceral intermingling of physical and psychological concerns via advances in technology gone sideways that are overtly terrifying, not to mention extremely icky, but which are also often seen as strangely liberating to those undergoing these changes. You would know that his films would often favor overtly metaphorical narratives that would share the screen with moments of unspeakably gruesome carnage and jet-black humor that could easily be mistaken for outright cruelty. You would also know that his films did not traffic in black-and-white situations with easily identifiable stalwart heroes and hiss-able villains. Even in a film like “Shivers,” for example, one could make the argument that while it is technically a monster movie, it is based around a creature that A) is only doing what it has been designed to do and B) is not so much destroying its victims as it is liberating them from their humdrum lives of quiet banality.

All of that is obvious now, to the point where one could argue that it is almost too overtly metaphorical for its own good (it is the kind of film that practically writes its own thesis paper on itself), but those running into it cold in 1975, presumably expecting 90 minutes of the usual sci-fi/horror silliness must have been poleaxed by it in the same way that the first viewers of George Romero’s “Night of the Living Dead” (1968) were when that film began shattering long-cherished cinematic taboos right and left a few years earlier. The shock and outrage that it inspired among viewers in its home country reached its apex when a writer from the Canadian film magazine Saturday Night decried it as repulsive trash in an article headlined “You Should Know How Bad This Movie Is. After All, You Paid For It.” You see, after spending a long while seeking funding for the film, Cronenberg finally got financing from the Canadian production company Cinepix (who had thus far specialized in software exploitation films and were looking for something edgier to help break into the American market) and the Canadian Film Development Corporation, a taxpayer-funded initiative. This inspired much hand-wringing and debate in Parliament over whether taxpayer funds should be given to a movie like that, a discussion complicated by the fact that it was one of the only movies made under those auspices to turn a genuine profit.

While it is easy to laugh at such excessive reactions today, one of the fascinating things about “Shivers” is that the ensuing 45 years have not dulled its power to shock and discombobulate viewers in any significant ways. Although Cronenberg’s story may owe some obvious debts to such classics as “Invasion of the Body Snatchers” (1956) and “Night of the Living Dead,” he pushes it in an entirely new and largely unexplored territory by frankly combining horror and eroticism in ways that veered between deeply disturbing and downright transgressive. (There are still a couple of moments that would be simply unthinkable in a film being produced in this day and age.) The film marked Cronenberg’s first exploration into the world of body horror that would soon become synonymous with his name and while subsequent efforts like “Videodrome” and “The Fly” may have explored it in a more elegant manner, the notion of a hyper-aggressive form of venereal disease that shatters taboos and wreaks societal havoc among the infected, who themselves become determined to spread the new goopy gospel to anyone they come across, is one that would be potent today even in a pandemic-free world.

Watching the film, it is obvious that Cronenberg is not just throwing gross-out images on the screen as an easy way of calling attention to himself—he is presenting an intelligently conceived and reasonably well-thought out exploration of the perils (and occasional pleasures) that can be found when the worlds of human biology and technological advancement are brought together in unusual way. This may have been the aspect that viewers found so disturbing back in the day—the fact that, for all of its B-movie trappings, this is a film made with intelligence and a philosophy (much like a certain cable channel that Cronenberg would later explore) and could not be laughed off as a joke. (Some observers have commented on the thematic similarities between the film and the J.G. Ballard novel High-Rise, in which the residents of another isolated hi-tech apartment wind up descending into an escalating orgy of sex and violence. As both the film and the book came out in the same year, that is unlikely but it could be easily argued that Cronenberg made a better and truer film version, however inadvertently, than Ben Wheatley did with his botch of an official 2015 adaptation.)

And yet, while “Shivers” is an undeniably strange and unnerving viewing experience, especially for those coming to it for the first time, it’s also quite a lot of fun. Although it does lack some of the formal precision and narrative tightness of his later movies, there is a ragged, exciting energy to it that comes from Cronenberg finding his way as a commercial filmmaker. Additionally, while he treats his premise fairly seriously throughout, he keeps the proceedings from becoming too overwhelmingly grim by leavening them with a welcome dose of dark humor that cuts through the gloom.

Over the years, the acting in the film has been critiqued for being somewhat stiff and bloodless and it is true that nominal hero Hampton comes across like the love child of Graham Chapman and a paint chip from the interior of a dentist’s office. However, the ordinary nature of most of the cast winds up fitting in with the film’s aesthetic—their blandness and sterility makes them the ideal fit for the world of Starliner Towers—and when it comes to the performers who do have distinct personalities, such as cult movie queens Steele and Lowry, he knows how to make use of their presence to killer effect. (Without going into particulars, the film’s climax simply would not have the creepy/arousing effect that it does without Lowry at its center.) Hell, even the creatures themselves hold up pretty well despite the obviously paltry effects budget—one could certain create more elaborate sex parasites than the ones seen here but it is hard to imagine that they could possibly come close to what is shown here in terms of sheer ghastliness.

If I were compelled to create a list ranking Cronenberg’s films from best to worst, “Shivers” would admittedly not make the top tier—his first unquestionably great movie would come a few years later with “The Brood” (1979) and it would have to get behind such additional stunners as “Videodrome,” “The Dead Zone” (1983), “The Fly,” “Dead Ringers” (1988), “Naked Lunch” (1991), “Crash” (1996), “A History of Violence” (2005) and “A Dangerous Mind” (2011) for starters. However, while Cronenberg’s commercial filmmaking career would prove over time to be an embarrassment of riches, its starting point was anything but an embarrassment. Made with startling intelligence and skill, this is a film that has not lost any of its potency over the decades and served as an announcement that Cronenberg was a filmmaker with an extraordinary amount of promise, which he would continue to live up to (and often exceed) throughout his career.

Cronenberg sadly did not record commentary tracks when Criterion did their special editions of “The Brood” and “Scanners.” But for “Shivers,” which is being released as one of the two initial entries in Lionsgate’s Vestron Video Collector’s Series (the other one being the Howie Mandel epic “Little Monsters” (1989), a nightmare film of an entirely different stripe), Cronenberg has recorded a self-effacing and reasonably serious minded track covering the production and the challenges of working on a more overtly commercially-minded production. The other new features created for this disc include a second commentary from co-producer Don Carmody (whose credits would run the gamut from “Porky’s” [1981] to “Chicago” [2002]), on-camera interviews with Cronenberg, Lynn Lowry, effects creator Joe Blasco and Canadian exploitation film expert Greg Dunning. Other items ported over from previous release include a 1998 interview with Cronenberg, a still gallery, an audio interview with deceased executive producer John Dunning and an array of trailers, commercials and radio ads that necessarily leaned hard on the more exploitable elements.

To order your Blu-ray copy of “Shivers,” click here