Twins seem a source of strange power to people who are not one.

Part of it must be in our imaginations. We see a nod or a glance between one twin and another, and we imagine some kind of telepathic communication taking place, when in fact the whole transaction is probably just ordinary body language.

Twins themselves always seem to keep some private place for their twinship. They do not talk about it much. They begin sentences that somehow seem to go nowhere, as if it is not quite possible to put into words what this particular relationship means to them. Most of us, I imagine, would like to have a twin; there is something awesome in the thought.

“Dead Ringers” is the vulgar exploitation-movie title given to David Cronenberg’s new film, which was originally and more poetically titled “Twins.” It stars Jeremy Irons in a dual role as Beverly and Elliot Mantle, brilliant twins who grow up to be brilliant gynecologists. Beverly’s name may be misleading; both twins are men, and they are unusually close, so much so that they routinely pretend to be each other.

The movie is not at all shy about exploiting the possibility that a woman going to see one of these gynecologists might end up being seen by the other. But that is only the beginning of their deception.

We discover that Elliot has always been the dominant twin, and that it is his practice to seduce a woman and then turn her over to Beverly – without telling the woman, of course. “You’d still be a virgin if it weren’t for me!” he cries.

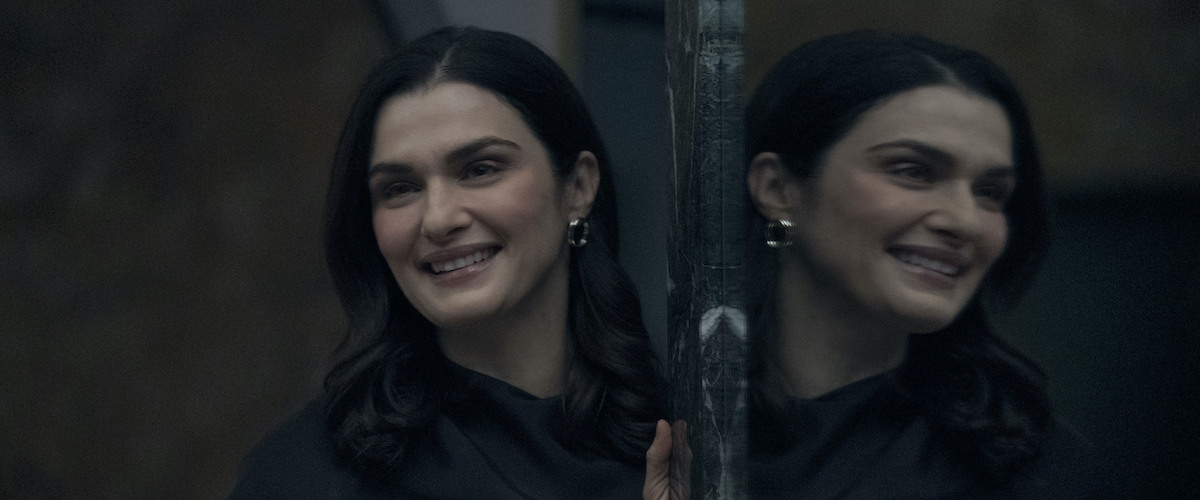

One of their girlfriends (Heidi Von Palleske) catches on. She is so genuinely in love with the one that she can detect the substitution. Her “real” lover apologizes, but does he mean it? Who would win out in such a tug-of-war? The girlfriend, or the twin? Then a famous actress (Genevieve Bujold) comes to consult them about why she cannot have children. The answer, in this most gynecologically precise of movies, is that she has three openings to her uterus, and an ambitious sperm is likely to get caught in traffic at the intersection.

Parts of the script seem lifted out of one of those women’s magazine articles that treat the reproductive organs like a biological subway system.

Bujold begins a kinky love affair with Beverly, and shares not only her body but her drug habit. The drugs seem to release the craziness that has always been potential inside of him, and although his twin tries to cover for him, their lives eventually fly into pieces. In one particularly gruesome sequence, Beverly invents some new surgical instruments that look like daydreams by the Marquis de Sade and uses them in a bloody operation that looks like what you do to the turkey before the stuffing goes in.

Does all of this work? On one level, it’s like a collaboration between med school and a supermarket tabloid. I saw it at the Toronto Film Festival with several women friends, who said it was harder for them to take than I, a man, could possibly imagine. But they were fascinated while it was on the screen. The secret may be that Cronenberg ( director of “The Dead Zone” and “The Fly”) approaches his trashy material with the objectivity of a scientist; it is his detached, cold style that makes the material creepy instead of simply sensational.

Of course everything depends on Irons’ performances as the twins. He is an intelligent, subtle actor, and he actually does succeed in making the twins into substantially different people. In ways so understated we are sometimes not even quite aware of them, he makes it clear most of them time whether we are looking at Beverly or Elliott.

He develops them separately, so that the chaos at the end really works.

Cronenberg is a master of special effects, as he demonstrated visibly in “The Fly” and as he demonstrates invisibly here. As everyone knows, when the same actor plays two characters in the same scene, one of the techniques used is the split screen. Clever viewers can usually spot the line – usually hidden in shadow – where one part of the picture ends and the other begins, but Cronenberg uses “moving splits” to fool them. Using computer technology, he can move the position of the split and the position of the camera at the same time, and he also sometimes drops in the split after one of the characters has just crossed the line where it will appear – so that we think that space is “real.” The result is that Irons convincingly appears as two separate people, and not as trick photography.

The technical perfection of the film is not matched by its emotional content. The story could have used more of the Bujold character, who is sophisticated and worldly enough to understand the twins, but who is dropped when they begin to retreat into their private disintegration. “Dead Ringers” is a stylistic tour de force, but it’s cold and creepy and centered on bleak despair. It’s the kind of movie where you ask people how they liked it, and they say, “Well, it was well made,” and then they wince.