We are pleased to offer an excerpt from the March edition of the online magazine Bright Wall/Dark Room. Their theme for this month is “Sacrifice” and, in addition to this essay by Thomas Zak on “The Last Temptation of Christ,” the issue also features new essays on “Uncut Gems,” “A League of Their Own,” “Fleabag,” “Suspiria” (2018), “The Favourite,” “The Son,” “All Quiet on the Western Front,” “Good Girls” and more.

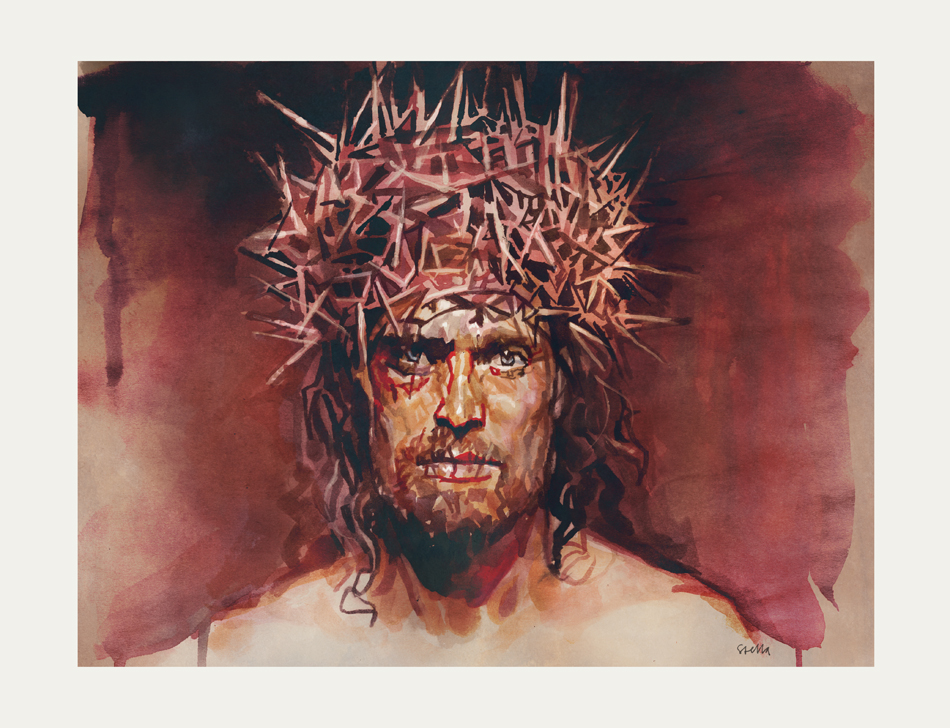

You can read our previous excerpts from the magazine by clicking here. To subscribe to Bright Wall/Dark Room, or look at their most recent essays, click here. The above art is by Tony Stella.

But Isaac spoke to Abraham his father and said, “My father!” And he said, “Here I am, my son.” Then he said, “Look, the fire and the wood, but where is the lamb for a burnt offering?”

-Genesis 22:7

As I type this, a framed photo sits to the left above my desk. It’s a behind-the-scenes look at the filming of the opening shot for The Hateful Eight, Christ on the cross, hanging on a crucifix of stone. A Savior frozen by the sins onscreen. Snow piles around him, making that spiritual and physical burden seem all the more heavy, vile, and cold. In a drawer below my desk, among the debris of pay-stubs, blunted colored pencils, and scraps of paper, lies a small, brittle, metal cross that once belonged to my grandfather. Its chain is tangled with paper clips, and the edges are chipped and tarnished away. Here salvation is weighed down by the mundane, the tedious, the forgotten, and the disregarded. Mercy mixes in with the miscellaneous.

Growing up, in the homes of friends and relatives, crosses were as present as pictures of family, perhaps even more so. Often my friends’ homes would have an entire wall dedicated to crosses of varying geometric and floral displays, a Christian equivalent of an altar and incense. It is accurate to say I was raised by suffering; the visions of God’s punishment were varied, everywhere, and never ceasing. Christ upon a cross of glass, Christ upon a cross of flowers. Christ upon a cross of rhinestones, Christ upon a cross of wire. A cross in the living room, in the window in the kitchen, on a candle on a bedside table, above the dashboard of a car, around a neck, in a pocket, on a body. The abundance of such displays was crushing; salvation determined by one’s proximity to pain. For a wedding present, some staff members at the church my wife and I attend gave us a stained-glass cross made by a renowned local artist. It is a dichroic cross, fashioned with rough copper, and colored with slits and rectangle glass patterns of royal purple, crimson, and various shades of blue. It sits wrapped in a paper bag atop an unused microwave in the corner of our downstairs closet. Why, I wonder, do I feel this aversion to the instrument meant to save me?

*

“Whoever does not carry his own cross and come after me cannot be my disciple.”

-Luke 14:27

If you’ve ever stepped into a Catholic church, it is unmistakable where the eye is supposed to linger. The crucifix. Christ’s whipped, bloodied, and malleable body hangs at the front, often in gargantuan proportions, in every cathedral. Sometimes the stations of the cross are displayed in the stained glass walls around the congregation, so that the light of the sun is literally filtered through the death of the Son. The lesson is clear, in the liturgy, in the sacraments, in the Eucharist: we are to know Christ and him crucified. Christ the sufferer. Christ the broken. Christ the disenchanted. Christ the dead. “The cross alone is our theology.” So says Martin Luther in his lectures on the Psalms. I confess this with my mind, but do I believe this in my heart?

In truth, the sacrifice of God makes me want to hide, makes me cower in fear at a being who would do that to himself. As I read Book of Common Prayer every day, I find myself ignoring, or glossing over certain parts of the prayers or Scriptures, concocting my own religion, something akin to Hazel Motes’ “Holy Church of Christ Without Christ” in Flannery O’Connor’s Wise Blood. I am asking, like Satan guised as an innocent girl in The Last Temptation of Christ, “If he saved Abraham’s son, don’t you think he’d want to save his own?”

Released in 1988, Martin Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ opened to uproarious controversy. Proclaiming to be “not based upon the Gospels but upon [a] fictional exploration of the eternal spiritual conflict,” this dramatic re-telling of the story of Christ led to massive boycotts, calls for the original print to be burned, and individual towns and cities seeking bans to prohibit the film’s premiere. Adapted from Nikos Kazantzakis’ novel of the same name (a novel for which the Greek Orthodox Church excommunicated him), Last Temptation remains to me a profound personal exploration into the very heart of Christian orthodoxy: the salvation of the world brought about by the sacrifice of the God/Man Messiah. In it I find Scorsese (raised a devout Catholic) wrestling with the same spiritual hesitancy that I do about the center of our faith: why did Christ have to die?

The film opens with a charged image: Christ making a cross, not for himself, but for the Romans to crucify someone else. Immediately Dafoe’s performance gives Jesus an intimate gravitas, delivering a Dean-like lament as Jesus expresses the anger of his complicities onscreen, “I want him to hate me! I want to crucify every one of his Messiahs!” The Son of God caught in frustration, the Son of God wanting to be abandoned, the Messiah asking to be left alone.

“You think it’s a blessing to know what God wants?” Jesus confesses to Jeroboam (Barry Miller) before his pilgrimage into the desert. “You want to know… who my God is? Fear. You look inside me and that’s all you’ll find.” This honest zealousness colors all the characters in Scorsese’s epic, from a blood-thirsty Judas (Harvey Keitel) whose knife seems to be always fresh with Roman blood, to a raving John the Baptist (Andre Gregory) whose followers make Coachella seem proper and prudish. Sacrifice is everywhere. Blood spills out of stomachs, lambs, necks, and hands. We see up-close the wounds on rotting skin and festering mounds of dead flesh as Lazarus sticks his hand out of the tomb, and we see him bleed on the ground days after his rising, murdered by Roman guards trying to silence a miracle. In a stunning scene of surrealism, Scorsese re-creates the devotion of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, with Christ literally pulling his beating, blood-dripping heart out of his chest with earnest intensity, and offering it to his bickering disciples.

Cinematographer Michael Ballhaus often backdrops the beige and barren world of biblical Jerusalem with streaks and flares of red: Fire dances off faces, silhouettes murders, illumines clouds of smoke, incarnates the Devil. Between the flames and the blood, the whole film feels like a Levitical offering, a slow, continual, primal drip, the Messiah steadily being poured out into the dust. Tables are turned. Wine is made from water. Stones are dropped. Bread is broken. The familiar sequence of events from the gospel narratives play themselves out, all the way up to Christ’s crucifixion.

Here, the heart of the controversy begins. As he hangs from the cross, a little girl (Juliette Caton), glowing and innocent as an angel, comes to the foot of the cross to tell Jesus he doesn’t have to die. She removes his crown, the nails from his feet and hands. She kisses his wounds. They walk away from Golgotha silently and unperceived, this sequence taking place in another dimension, an alternate reality, or a separate spiritual sphere, while the crowd jeers at an empty cross. She leads him to a verdant valley, where he and Mary Magdalene (Barbara Hershey) are married. Later, he is seen with kids, and later still, he encounters the Apostle Paul (Harry Dean Stanton) and denies his very death, which Paul is preaching about. On his last days, as an elderly Jesus lays on his deathbed, some of the disciples encounter him in his room, whereupon they point out to Jesus that his young angel companion is actually Satan in disguise. Jesus, realizing his and all of humanity’s fate, painfully climbs out of his bed and outside into a burning Jerusalem, only to be transported back to the cross, where he now hangs smiling and triumphant, before he dies.

I would be lying to myself if I said this sequence, as a Christian, is an easy thing to watch. It is not. There are many images here that jar the mind out of the bounds of orthodoxy, and unsettle one’s spirit to even contemplate, let alone see. Christ having sex with a woman. Christ denying his death. Christ walking away from the cross. I find the very image of an empty cross, a cross unburdened from holding the sins of the world, to be one of my personal coldest moments in all of cinema. It is a resolute “No” to the gruesome savagery that I pin my hopes on, a cold reality that the Savior of the world could have come down from the cross had he wanted to, and left Golgotha empty. Yet this image remains indelible for another reason: it is an alternate past that I want to happen. Christ free from his obligation. Christ alive and living. Christ not dying, let alone dying for me. A cross-less religion. I find here my own comparable desert test: Why, I must try to answer, did God not save his only Son?

While Scorsese leaves ample room for theological reflection, he forces you to sit with your own doubts and closet ambiguities. Could Jesus have ultimately chosen a human life? Would he have been wrong to do so? This “last temptation” sequence is not a quick edit, nor a short side-step from the passion of the cross. It is a tumultuous (for the orthodox-inclined) 31 minutes in length. This is Scorsese’s own passion, his own last temptation, his own quiet celluloid confession for the world to see. By giving this alternate ending to the Christ-saga so much screen time, Scorsese validates his own wrestling with his faith as something to be dug into, not ignored. It is only by lifting the veil of Christ’s divinity that Scorsese believes we might understand how truly human Christ was. The most harrowing aspect of this re-telling suddenly becomes the most reverential: if Christ was a man just as I am, then his sacrifice came with the same temptations that I face. The temptation to turn away, to abandon, to deny. The temptation to indulge my heart’s desires, the temptation to ignore the suffering around me. To watch The Last Temptation of Christ is to enter the basement of your own private stammerings, those un-uttered fearful prayers of a theological imagination gone awry. He could have come down from the cross. He could have led a peaceful life and raised a family. He could have died in peace in a remote house in a remote village, surrounded by the ones he loved. But he didn’t. He died on a small, fetid hill, bloodied and beaten, scorned and scoffed at, forgotten and alone.

*

“He Himself bore our sins in His body on the cross, so that we might die and live to righteousness; for by His wounds you are healed”

-1 Peter 2:24

The last frames of Last Temptation hold a unique story of their own, and an accidental answer to Scorsese’s restless spiritual pilgrimage. After we jump back to the scene of the crucifixion, Christ utters his final words: “It is accomplished!” (According to St. John, these were Jesus’ words on the cross. The greek: Tetelestai, or, “It is finished”) We linger on the hung and crucified Messiah, when all of a sudden light seeps into the film grain. First an exposure of the all too familiar red, then white, then a phantasma of shades and colors, a miniature Shirley Clarke film, before the triumphant bells of Peter Gabriel’s score break through and the credits start to roll. Not discovered until the film was developed, this whiteout takes on its own theological fervor: is this the epiphany of the Messiah, his Spirit ascending from his mortal frame? Is this the soul of the Savior unbound from the sacrificial offering that took his life, the glory of God displayed in 35mm? “His face shone like the sun, and his clothes became as white as the light.” (Matthew 17:2) Could this be Scorsese’s own transfiguration, Christ joining again the dance of the Trinity, the agony of the cross melting in a Kandinsky-like swirl to the presence of the divine?

In his preface to Shūsaku Endo’s Silence, Scorsese writes, “Questioning may lead to great loneliness, but if it co-exists with faith—true faith, abiding faith—it can end in the most joyful sense of communion.” I believe Scorsese’s question in The Last Temptation is this: Could Jesus have doubted the very purpose of his death? If so, I must ask myself: Can I allow Jesus the same shroud of uncertainty that I have? Can I allow my Messiah the messiness of being human? If I miss the aspect of God’s shared humanity, I commit myself to never understanding my own. Christ’s body becomes a conduit, a skin suit, a temporary entrapment for the divine. If I over-insist on the divinity of the Messiah, I end up concocting a myth whereby Christ comes to Earth for the convenience of my soul but not for the resurrection of my body. What am I to do with the pains inside me, the nails of fear that claw my head like ravens, the moments of lustful passion that convulse my lungs, the doubts I harbor alone and awake in the middle of the night? My Messiah must be hot-blooded, must have the capacity for rage like I do, the ability to long for blindness to the world’s atrocities and my neighbor’s sufferings, the natural resolute hardness of heart to deny God and his mercy at work in the world. He must be broken and be able to be led astray, thought to be abandoned, tortured by the life he cannot live or isn’t living. I need a God ransacked by the weight of time’s demand, a God crushed by a burden he believes he cannot fill, a God who bleeds. In short, am I willing to make Christ like myself, so that He might make me like Himself? This is the tortured argument at the heart of The Last Temptation of Christ. In probing the depth of Jesus’s humanity, Scorsese makes the sacrifice of Christ all the more fulfilling, real, tortured, and true.