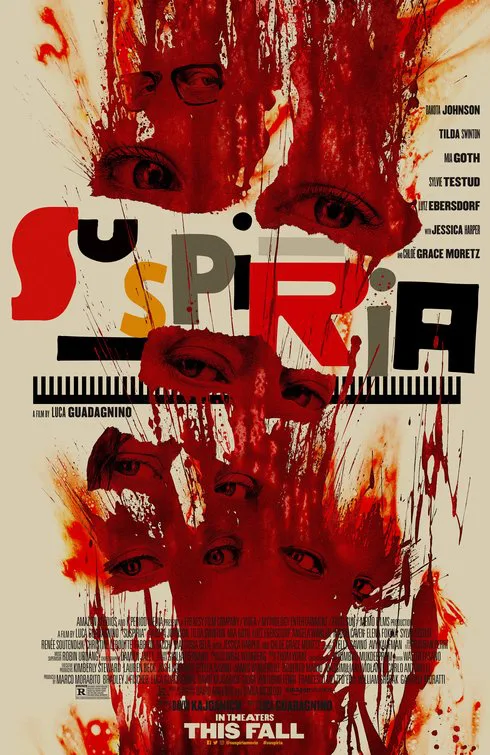

Luca Guadagnino’s “Suspiria” isn’t so much a remake of the 1977 Dario Argento horror classic as it is a seriously insane (and seriously serious) expansion on the original. The two films share a setting, a few character names and a basic premise—that a prestigious German dance academy is a front for a witches’ coven, because of course it is—and that’s about it.

So if you love Argento’s lush and lurid Giallo phantasmagoria, you might wonder what exactly is happening here—or rather, when. Guadagnino creates an unsettling mood off the top, with a soaked and sallow young dancer dashing into her shrink’s office, spewing paranoid babble. And the score from Radiohead genius Thom Yorke creates an inescapable feeling of melancholy and mystery; his haunting, three-quarter time piano theme, titled “Suspirium,” plays over images of a woman’s body being lovingly cleansed as she lies in her sickbed. But Guadagnino takes his time in exploring the cruel contours of this place, an Escher painting of stone stairways and dark halls where pained sighs linger and wicked laughter echoes. For a while, Dakota Johnson’s long, red braid is the film’s primary source of color. It will all explode into a blood-red orgy eventually, but for a long time, we are fully ensconced in the chilly discomfort of perpetually rainy 1977 Berlin.

“Suspiria” is as striking and severe as the director’s “Call Me by Your Name,” the best film of 2017, was warm and welcoming. He could have shocked you quickly with cheap scares. Instead, he’s in it for the long haul, insidiously working his way under your skin to disturb you deeply. And for the most part, he succeeds, even as he frustratingly undermines himself with an overstuffed script from David Kajganich (who also wrote the screenplay for Guadagnino’s “A Bigger Splash”). The problem is that while “Suspiria” has a vivid and specific sense of place, it also strives to exist in the outside world with a larger historical context in a way that never connects.

The film aims to say something about the futility of trying to escape the past, despite fervent efforts at rebirth. The fact that “Suspiria” boasts a powerful, predominately female cast – led by Johnson, Mia Goth, Angela Winkler, Ingrid Caven and multiple Tilda Swintons – certainly speaks to the formidable nature of feminine strength. But just as he’s building a steady, suspenseful momentum, Guadagnino too often cuts away to the tumult encompassing all of Berlin: a city split in two, struggling to reestablish itself post-Nazism, but still being torn apart by attacks from the leftist Baader-Meinhof Group. That feels like an entirely different film, one that blends ambitiously yet awkwardly with the story at the stylishly rotting core of “Suspiria.”

Truly, watching Swinton and Johnson stare each other down in dance spaces and restaurants in an array of brown and gray period garb, their psychic connection piercing the ever-present cigarette smoke, is enough of a satisfying meal. (The co-stars of “A Bigger Splash” reunite with Guadagnino, once again bringing the alluring alchemy of their contrasting screen presences.) “Call Me by Your Name” cinematographer Sayombhu Mukdeeprom soaks every scene in sadness and fear—even moments of theoretical creative joy are awash in an avant-garde gloom. And yet, evil is obviously lurking, gathering itself and finding ways to rear its head.

Into this dark world enters sweet Susie. Johnson uses her light, girlish voice—which carries hints of her mother, Melanie Griffith’s—to her advantage in the film’s early scenes as a shy but ambitious new student at the Helena Markos Dance Company. (It would be easy to underestimate Johnson based on her starring role in the “50 Shades” trilogy, but she is an actress of understated, unexpected power who continues to display her versatility.) Susie had dreamed of studying there since she was a child growing up in a religiously conservative family on an Ohio farm. Now that she’s arrived, she wastes little time in impressing the school’s legendary choreographer, Swinton’s swanlike but stern Madame Blanc. (Swinton, Gudagnino’s longtime friend and muse, is a steely force of nature and fascinating to watch, as always.) Shooting in 35mm, Guadagnino uses ‘70s-style zooms and off-kilter camera angles early on to create a feeling of unease and imbalance. Susie and Blanc are forming a connection, and it might not necessarily be for the good.

This is most powerfully clear in the film’s tour-de-force scene, when Susie volunteers to dance the lead role in the company’s signature piece after having spent only a couple of days there. As she stomps, crawls, leaps and twists to Blanc’s modern moves, another dancer—trapped in a rehearsal space one floor below—finds herself being yanked violently around the mirrored room, her body contorted in excruciating ways that match the choreography upstairs. She is the world’s most flexible voodoo doll, and it is horrifying. Guadagnino and his longtime editor, Walter Fasano, crosscut seamlessly and thrillingly between both rooms as the dancers build to their respective crescendos. By the end, both are spent, but in vastly different ways.

Guadagnino’s technical brilliance also is on display in a gorgeous and fluid sequence in the school’s dining room and kitchen, his camera panning around over and over as they fill up with food and instructors chatting, eating, milling about. One of the rare sources of humor in this bleak realm is the way in which the chain-smoking, hard-partying teachers interact with each other, their sadistic cackles filling the halls and fueling their fiendish deeds. They’re having so much fun, you almost want to join them—and they’re hoping that Susie, the pure vessel they’ve long sought, will do just that.

But two people who suspect strange things are afoot within the dance company begin investigating, at their own peril. One is vivacious fellow dancer Sara (Goth), the first person to befriend Susie and the first to recognize the transformation she’s undergoing. The other is the aforementioned psychiatrist from the film’s start, Dr. Josef Klemperer. He’s “officially” credited as being played by Lutz Ebersdorf but is actually Swinton, again, beneath layers of convincing and detailed old-man makeup. Why? For the hell of it, but the performance is consistent with the shape-shifting Swinton’s penchant for toying with traditional gender roles, and it provides some genuine moments of pathos.

Never mind the well-intentioned doctor’s involvement, though. Men are essentially useless in the world of “Suspiria.” They exist to be mocked and manipulated. Female energy is all that matters, and it is overwhelming in the film’s truly gonzo finale. You will stagger out of the theater wondering what exactly you just saw, but you will not easily forget it. But maybe that’s Guadagnino’s point in incorporating outside troubles into this intense, insular tale: Men got us into the problems that plague the world. Women can get us out—but that liberation comes at a cost.