For many years, when people would think about the French New Wave film movement that revolutionized the world of cinema in the late 1950s, their thoughts would drift to the most famous names—Godard, Truffaut, Rivette, Chabrol, Resnais and others. One name that rarely came up in the conversation, however, was that of Jacques Demy. Even though he was making films during that time and achieved some degree of international success, many observers considered his contributions to be either too tangential or too dependent on Hollywood traditions and his own self-created cinematic universe to fully embrace the formal radicalism of the movement. In fact, when he was discussed as part of the New Wave, it was often because of his marriage to Agnes Varda, a filmmaker whose work was more firmly entrenched as part of the approach, and that semi-snubbing continued until he passed away in 1990 at the age of 59.

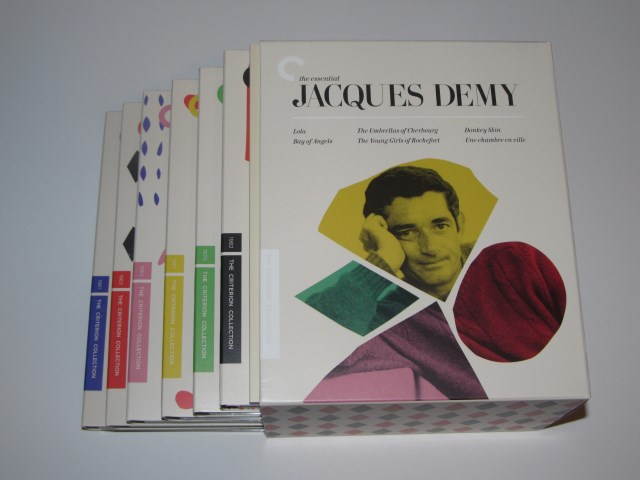

In the years since his passing, however, there has been a gradual reappraisal of Demy’s cinematic legacy, spurred on in no small part by the efforts of Varda, who has helped to keep the flame alive by supervising restorations and reissues of his films as well as directing both “Jacquot de Nantes,” a 1991 biopic focused on his early years, and the 1995 documentary “The World of Jacques Demy.” Now The Criterion Collection has gotten into the act with “The Essential Jacques Demy,” a mammoth box set that includes restored versions of six of his best-known features—”Lola” (1961), “Bay of Angels” (1963), “The Umbrellas of Cherbourg” (1964), “The Young Girls of Rochefort” (1967), “Donkey Skin” (1970) and “Une Chambre En Ville” (1982)—a slew of extras spanning the length of his career, including shorts, documentaries and archival interviews with Demy and many of his key collaborators, and a booklet featuring essays from such renowned critics as Terrence Rafferty and Jonathan Rosenbaum. The end result is one of the major home video releases of the year and a project that should finally restore Demy’s place as one of the leading lights of the New Wave.

One of the reasons why his films were often dismissed back in the day, despite (or perhaps because of) their commercial success, was because his work seemed to some observers to be insular and out of step with that of his colleagues. While they were out challenging the ways in which films could be made and the stories they could tell, Demy was content to create a largely self-contained universe in which everything was just a little more heightened than in real life, and where the stories referenced such equally stylized genres as musicals and fairy tales. For those who were on his unique wavelength, the results were gorgeous and deeply felt fantasias of music, color and emotion. For those who didn’t respond to his particular brand of filmmaking, the results could come across as the irredeemably twee ramblings of a director either unwilling or unable to deal with the real world around him. In other words, he was sort of the Wes Anderson of his day.

“Lola”

“Lola” was Demy’s first feature and is probably the film that most closely fits in with what one thinks of when one thinks about the New Wave. Set in Demy’s hometown of Nantes, the film stars Anouk Aimee as Lola, a cabaret singer who yearns for the return of Michel, her long-lost love and the father of her seven-year-old child, though she is not above entertaining Frankie (Alan Scott), a sailor from Chicago on leave who reminds her of Michel. One day, she happens to run into another old flame, the still-smitten Roland (Marc Michel), who has returned to town and who gets involved with a shady diamond enterprise in order to earn money to take Lola away from all of this. Hovering on the periphery is Cecile (Annie Duperoux), a 14-year-old girl who winds up befriending both Roland—who is struck by her similarity to the young Lola (whose real name, we learn, is Cecile)—and Frankie, with whom she spends a day at a local amusement park before he departs, and a white-clad stranger (Jacques Harden) who may or may not be Michel.

Watching “Lola” today, it is hard to understand why it never became a New Wave classic on the level of “Jules & Jim” and “Breathless.” It shares many common traits with those films—nice, naturalistic performances from the cast, lively cinematography on the streets of Nantes that is evocative enough to virtually make the city into another character (a possible result of Demy having gotten his start working in documentaries) and numerous allusions to other films woven into the narrative—and handles them with the kind of skill that belied the fact that this was his debut feature. That said, there are key differences that set it apart from the others. For one thing, while a film like “Breathless” took a good chunk of its power from the way that it felt as if everything was unfolding with the happenstance of real life, the intricate interplay between the characters here is as highly choreographed as a production number in a big musical.

More significantly, while Demy’s film has as much romance as those of his contemporaries, his romance is much more pessimistic—in the end, most of the characters end up alone and even the one who seems to get exactly what they wanted has their happiness undercut in its final moments. Some may find the film to be a downer in the end because of it but I find that by adding a certain darkness to the material, Demy transforms what could have been frothy nonsense into something more substantial and ultimately more rewarding—a move that he would continue to make throughout his career.

“Bay of Angels”

That blend of blissfulness and pessimism continued in Demy’s next film, “Bay of Angels,” in which we follow a character as he moves from his mundane reality into a more fantastic world that inspires him to remark at one point “I didn’t think such a lifestyle existed anymore…Except in the movies or certain American novels.” This is Jean (Claude Mann), a straitlaced Parisian bank clerk, who, as the story opens, is dragged halfheartedly by a friend to a Belgian casino for an afternoon of gambling. The experience confuses and unsettles him at first, but after winning a bunch of money at roulette, he decides to head to the Riviera to try his luck at the casinos there, albeit in the most careful and cautious manner possible. There he meets Jackie (Jeanne Moreau), an inveterate gambler whom he first sees as she is being barred from a casino for life. The two get together and tour the other gaming spots without a care in the world and barely noticing whether they are winning or losing. As time passes, however, the initial luster fades away and Jean realizes that Jacki’s only true love in life is gambling—it brought about the end of her first marriage when she picked it over her husband—and he has to decide whether to return to his former cautious life or follow her into an existence where virtually everything is dependent on the roll of a roulette ball.

The notion of a couple falling in love amidst the glamorous casinos of the Riviera sounds like the ultimate in romantic fantasy but, as he did in “Lola,” Demy doesn’t hesitate to subvert audience expectations at virtually every turn. There is very little in the way of plot (no plans to rob the casino or a big tournament), not much in the way of suspense (the gambling is depicted as such a blur of noise and movement that it is impossible to fully grasp what is happening) and no characters of note outside of Jean and Jacki. And yet, it is this lack of import throughout—the arbitrary nature of their lives and their relationship—that ultimately drives the film. As Terrence Rafferty points out in his essay, without it, the powerful final scene simply wouldn’t work. The other key to the success of “Bay of Angels” is the impressive central performance by Jeanne Moreau who, with her Jackie-O wardrobe and Marilyn Monroe wig covering, but not obscuring, her decidedly down-to-earth features, she embodies the tug-of-war between fantasy and reality to such a degree that she is arguably the key character of Demy’s entire filmography.

“The Umbrellas of Cherbourg”

Demy’s third feature, 1964’s “The Umbrellas of Cherbourg,” would be his big international breakthrough—it would win the top prize at that year’s Cannes Film Festival, become a hit in America and become one of the first big hits for leading lady Catherine Deneuve—and continues to be regularly reissued to the delight of old fans and new converts to the cause. The film tells the story of the romance that develops between Genevieve (Deneuve), the beautiful daughter of Madame Emery (Anne Vernon), the owner of the local umbrella shop, and Guy (Nino Castelnuovo), a poor-but-handsome garage mechanic. Guy and Genevieve are in the full throes of first love—at one point, we literally see them floating down the street together in rapturous bliss—but Genevieve’s practical-minded mother, worried about her daughter’s future with someone with so few prospects (and not without reason), tries to point her in the direction of a visiting jeweler named Roland (Marc Michel and, yes, this is the same character that previously appeared in “Lola” a couple of years earlier).

Everything changes when Guy is called up to fight in the war in Algeria and he and Genevieve spend one final night together doing what most people in such a situation generally do. Perhaps inevitably, Guy’s letters to his beloved become less and less frequent as, perhaps even more inevitably (though unbeknownst to him), Genevieve becomes more and more pregnant and in need of someone to provide for her. At this point, Roland comes back into the fold and he winds up marrying Genevieve. Time passes and Guy, physically and emotionally scarred by his service, returns to a town that once seemed so bright and full of promise but which now seems duller without the one-time love of his life but even he is allowed a second chance at happiness. It all leads to one of the great tear-jerking finales of all time in which a few years have passed and the paths of the two young lovers unexpectedly cross at an Esso station at Christmastime. Oh wait—did I mention that the film is a musical in which every line of dialogue is sung to an ever-swelling score by Michel Legrand?

For those who have never encountered the film before, the above description must have made the film sound like the most ridiculous load of treacle even before learning that it was a musical—a French musical, no less. And yet, to describe “The Umbrellas of Cherbourg” to someone who has never seen it is a lot like trying to describe a Monty Python routine to someone who is unfamiliar with the group—you can recount what happens but not so much how it happens, and that makes all the difference. Shooting in color for the first time and taking his first full-on stab at the musical genre that he had hinted at with his previous features, the film appears at first to be a case of Demy fully embracing the love of screen artifice and boldly stepping away from the more realistic earlier efforts. In that respect, he has indeed made the kind of film that audiences in the right frame of mind might literally swoon to—the colors (at least in the first two-thirds or so) are heightened to an eye-popping level and Legrand’s score is as romantic and rapturous as can be. At first blush, this isn’t just a romantic movie musical—this is a romantic movie musical’s most perfectly idealized dream of itself.

The film is glorious—all the more so because this relatively low-key production hit theaters at the point when the movie musical began turning exclusively to lumbering adaptations of Broadway hits that were generally too long, too expensive and too weighty for their own good—but the cynics who continue to dismiss it as too sweet and too twee for its own good may be surprised to discover just much it subverts the conventions of the movie musical, normally the most heedless of cinematic genres, especially back in those days. Yes, the early scenes are as stylized as can be—everything is bright and colorful as can be and the young lovers are as delightful as can be (with the then-twenty-year-old Deneuve looking so impossibly gorgeous that you practically have to smack yourself in the head out of sheer disbelief that such a person could have possibly existed)—but as the fortunes and circumstances of Guy and Genevieve begin to shift and change, everything from the mood to the music to the color scheme gets darker and more muted as the excitement of their romance inevitably fades in the face of real life. And yet, this is no mere act of cynicism on Demy’s part—the darkness and the light are blended together so effortlessly that it is ultimately impossible to separate the two.

“The Young Girls of Rochefort”

Thanks to the international success of “The Umbrellas of Cherbourg,” Demy was able to go bigger, brighter and bolder than ever before with his follow-up project, the eye-popping, jaw-dropping, heart-swooning 1967 masterpiece that is “The Young Girls of Rochefort.” A semi-sequel, at least thematically, to “Cherbourg,” this film found Demy working on a larger scale than he had ever attempted before with such elements as another musical score from Michel Legrand, the streets of the gorgeous seashore town of Rochefort, a pastel-heavy color scheme, an expanded running time (at 126 minutes, it runs almost a half-hour longer than virtually all of his other films) and a cast including some of the most famous faces in French cinema at the time and an American virtually synonymous with the Hollywood-style musicals he was trying to emulate here. Some directors used to working on smaller-scale projects might have gotten swamped by all of these ingredients but Demy handles them beautifully and the result is not just the best film of his career but one of the true landmarks of French cinema.

Set over the course of a single weekend, the film is another musical confection centered on the chance encounters and missed connections that occur (or don’t) between the featured characters. At the center of it all are twin sisters Delphine (Catherine Deneuve) and Solange (Francoise Dorleac, Denueve’s real-life sister, though not her twin, who would tragically perish in an auto accident shortly after the film’s premiere), two young women with artistic ambitions—Delphine teaches ballet and Solange wants to be a composer—who yearn to leave their small town for the glamor and excitement of Paris. Their mother, Yvonne (Danielle Darrieux), runs the local cafe where many of the locals congregate as well as Etienne (George Chakiris) and Bill (Grover Dale,) two carnies working with the fair setting up shop in the town square, and Maxence (Jacques Perrin), a sailor and would-be artist whose painting of his ideal woman now hangs in the gallery belonging to Guillaume (Jacques Riberolles)—ironic since a.) the woman in the painting is a dead ringer for Delphine and b.) Guillaume just happens to be Delphine’s on/off boyfriend.

Yvonne is also the mother to a young son but backed out of marrying his father, Simon Dame (Michel Piccoli), because she was horrified at the idea of being known as Madame Dame. What she doesn’t realize is that not only has Simon returned to town after a long absence to open a music store but has befriended Solange (whom he has never met) and promises to put her in contact with Andy (Gene Kelly) an American composer friend who is visiting for a few days. As the film progresses, the characters keep walking in and out of each other’s lives, often without realizing it—Andy and Solange bump into each other on the street but do not introduce themselves (though Andy retrieves a page of music that she has dropped and is smitten by her work) while Delphine just misses meeting Maxence by mere seconds. Eventually, the sisters’ dream of leaving appears to come true when two of the dancers from the fair skip town with a couple of sailors and Etienne and Bill lure them into replacing them for the big show on Sunday with the promise of free passage to Paris. Oh yeah, lurking on the outskirts of all of this is an ax murderer whose crimes inspire no fewer than two musical moments, one of them staged at the murder scene, no less (and wait until you discover the identity of the victim).

“The Young Girls of Rochefort” finds Demy playing with the juxtaposition of dreamy fantasy and down-to-earth reality but comes up with a number of dazzlingly inventive variations on that theme. Instead of bursting out into full-scale production numbers for the musical moments, for example, he stages them in a more complex manner. Although the film is clearly besotted with the idea of American musicals—besides the presence of Kelly and Chakiris, there are visual homages and allusions to such classics as “An American in Paris,” “On the Town” and “Gentlemen Prefer Blondes”—it is, as a whole, still quintessentially French in terms of its storytelling and characters. Take the ending. While Demy’s films have often had endings that were bittersweet or pessimistic, most Hollywood musicals to this point insisted upon happy endings as a convention of the genre. Demy somehow manages to find a balance between the two extremes that allows him to satisfy both impulses in a graceful and oddly satisfying manner.

Even if you have never seen a Jacques Demy film before, “The Young Girls of Rochefort” is still a dazzling achievement. Ghislain Cloquet’s cinematography is absolutely stunning in the way that he perfectly captures the pastel-hued paradise in all of its glory—if nothing else, this is certainly one of the most beautiful-looking movies of its era. Although the story is essentially more than two hours of people just missing each other, it never grows tedious and some of the close calls (especially the one where Maxence and Delphine miss each other by maybe a second or two) are so deftly handled that viewers will be both thrilled by the cinematic craft and frustrated that the two characters have once again failed to get together. Legrand’s score is even more infectious than his music for “The Umbrellas of Cherbourg” (and would go on to win an Oscar nomination for Original Score). The performances are similarly delightful—Deneuve is gorgeous and charming, Kelly is full of energy and high spirits in what would prove to be his last great musical (To anyone planning on writing in to chastise me for overlooking “Xanadu“…don’t) and Dorleac is so much fun to watch that it is impossible to believe that she would be dead before too long. For those interested in more details about the film and its history, the extras on this disc include “The Young Girls Turn 25,” a 1993 documentary on the film and its legacy by Agnes Varda that is pretty much required viewing.

“Donkey Skin”

After traveling to America to make his first and only Hollywood film, 1969’s “Model Shop,” (not included here), Demy returned to France to make what may well be the weirdest film of his entire career, “Donkey Skin.” While his previous films could be loosely described as live-action musical fairy tales, that is exactly what this unabashed fairy tale is. Inspired by the children’s tale by Charles Perrault, the film opens as the King (Jean Marais) makes a vow to his dying queen that if he remarries, it will be to someone just as beautiful and pure as she. Alas, the only woman who seems to fit all of his criteria is his own daughter, the Princess (Catherine Deneuve), and while he sees no problems with that, she has a few qualms. On the advice of the Lilac Fairy (Delphine Seyrig), her fairy godmother, she agrees to marry her father only if he performs a series of impossible tasks, including providing her with the skin of the magical jewel-excreting donkey that is the source of the kingdom’s fortune. When he performs all the tasks, she disguises herself in the donkey skin and flees for a nearby kingdom where, still disguised in the skin, she gets a job as a scullery maid for the Prince (Jacques Perrin), who finds himself falling for this mysterious girl without realizing who she is.

With its intriguing use of special effects, the use of live actors to portray seemingly living statues and the presence of the great Jean Marais in the cast, “Donkey Skin” clearly owes an enormous debt to Jean Cocteau’s classic 1946 version of “Beauty and the Beast.” However, while Cocteau generally embraced the traditions of the fairy tale, Demy subverts them here throughout in weird, wild and potentially disturbing ways. Although the incest theme is handled in a more metaphorical manner than anything else (though he would deal with the subject in a more direct manner in his final feature, 1988’s “Three Seats for the 26th”), he does take the sometimes disturbing underpinnings of the classic fairy tales (at least the non-bowdlerized versions) and deals with them directly. It is interesting to note, for example, that the Princess opposes her father’s proposal on the advice of her fairy godmother, who wants the king for himself, and when she gets to marry the handsome prince at the end, it is fairly well apparent that things may not end happily ever after, especially when she learns that her father and her fairy godmother are also to be wed. (“I’m marrying your father, dear. Try to look pleased”).

It is all interesting in theory, I suppose, but watching Demy telling a story in an overtly artificial atmosphere and subverting the conventions of fairy tales just seems kind of silly today. The film looks beautiful and Demy creates a convincing fantasy atmosphere but with nothing to counterbalance it other than the exceptionally strange premise, it just feels odd and not always in a good way.

“Une Chambre en Ville”

The last film in the set, “Une Chambre en Ville,” is the only one that I had not previously seen prior to the release of this set—it was a box-office flop when it was released in 1982 and was difficult to see thereafter. The film is another sung-through musical, though one of a decidedly darker tone than his other efforts in the form. Set in his hometown of Nantes in the Fifties during the time of a violent workers’ strike, the film follows Edith (Dominique Sanda), a woman unhappily married to a violent and jealous shop owner (Michel Piccoli) who yearns to run off with her steelworker lover Francois (Richard Berry), even though he is still involved with Violette (Fabienne Guyon), who, it turns out, is pregnant. To add to the confusion, Francois is boarding at Edith’s house with her mother (Danielle Darrieux), who is convinced that her roomer is actually a communist. Once again, the characters bounce in and out of each other’s lives in surprising ways but this time around, events tend to take a grimmer turn than has been the case in the past.

Having only seen the film for the first time a few days ago, my feelings towards it are still unsettled. It is such a crazy film that it hardly seems to be the work of a veteran director at the twilight of his career—with the extremes that it goes to in regards to nudity (Sanda spends much of the film wearing a full-length fur coat and nothing else), violence (including a couple of violent clashes between the workers and the police and a confrontation between Edith and her husband that is the most shockingly brutal moment of his entire filmography) and narrative approach (even if it wasn’t a musical, it would almost certainly still be described as “operatic”), it feels more like a work from the likes of Leos Carax, Jean-Jacques Beineix or one of the other young French filmmakers just starting out at the time that it was released. Combine that with a story that no sane person would dare to musicalize and you have a film that is far more difficult to get into than most of Demy’s previous works.

And yet, there are things about it that are undeniably intriguing. Sanda makes for an interesting presence (though one wonders what it might have been like if Deneuve, who was Demy’s initial choice, had played the part), the music (composed by Michel Colombier, one of the few time in which Demy did not work with Legrand) is appropriately dark and moody and I was impressed by the way that he presented the bleak material in a largely non-judgmental manner (with even the nasty husband ultimately being presented in a empathetic light) without sugar-coating things. It may not be Demy’s finest work but, as is the case with virtually everything else in this magnificent collection, I am certain that I will be going back to revisit it again and again.