“For relief you can trust, trust Tylenol. Hospitals do.” — From a 1981 TV commercial for Tylenol.

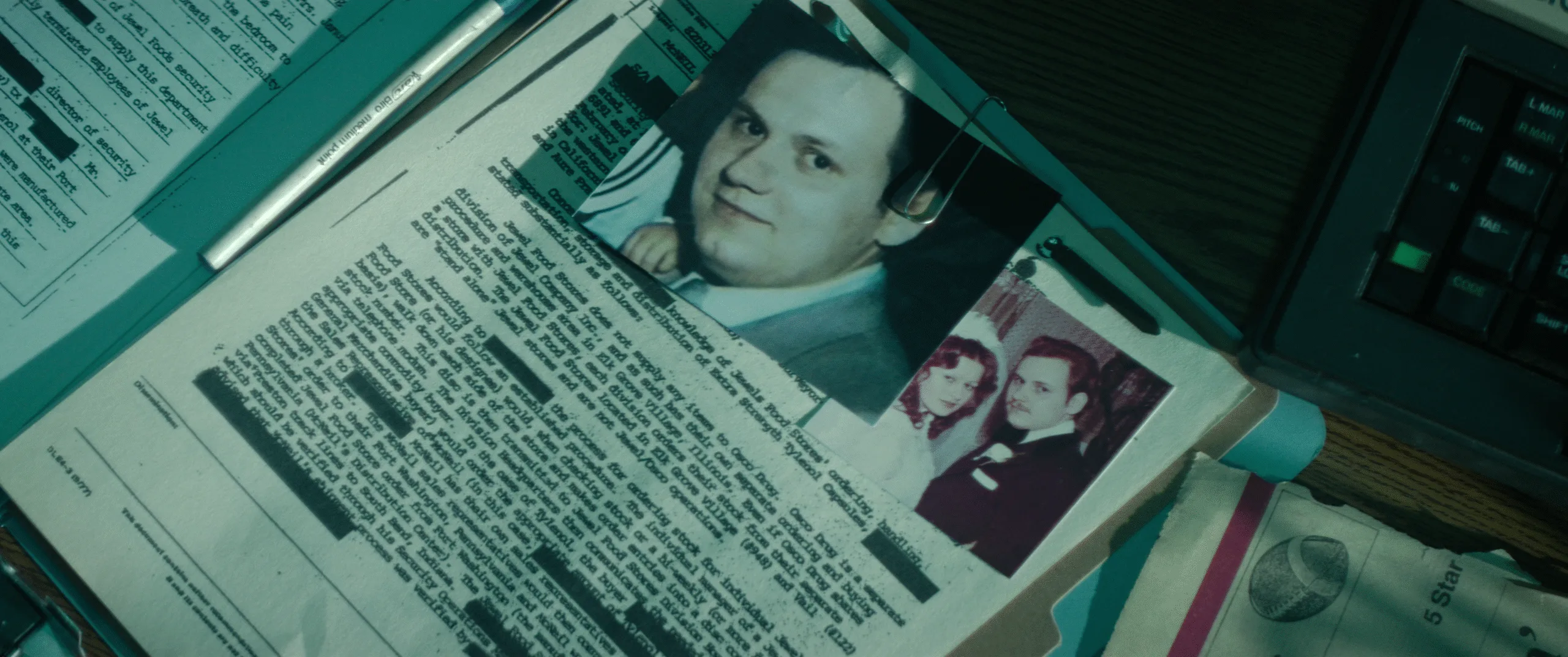

In the second episode of the three-part Netflix true crime documentary series “Cold Case: The Tylenol Murders,” James Lewis fiddles with a box of Extra Strength Tylenol some four decades after he became the prime suspect in the case, and says to the off-camera filmmakers, “You think I’m going to open this and get my fingerprints all over?”

His face masked in a kind of semi-rictus grin, Lewis struggles with the foil seal on the bottle, noting, “It’s pretty well sealed…Everyone opens a bottle and swears my name.” It’s a creepy and chilling moment in the last interview conducted with Lewis before he died in July 2023—but he wasn’t wrong about people cursing his name.

For those of us who remember the Tylenol murders of 1982, particularly those of us who lived in the Chicago area, it’s virtually impossible not to think of that horrific chapter in our history every time we struggle a bit with a shrink band on a beverage bottle, induction seals on personal care products or the glued-shut outer box, plastic cap seal or foil seal under the cap on Tylenol and other over the counter medications. There were some types of tamper-resistant packaging available before the Tylenol murders, such as blister packaging for certain kinds of tablets and capsules. Still, it was the shocking killings of seven innocent people who took Tylenol capsules laced with potassium cyanide that brought about the era of widespread and regulated Tamper Resistant Packaging.

“Cold Case: The Tylenol Murders” is the second documentary series to revisit the case in recent years, on the heels of the five-part Paramount+ project titled “Painkiller: The Tylenol Murders” in 2023. (I gave that series three stars at the time.) Much of the latter series focused on the efforts of then 13-year-old Isabel Janus and her efforts to find answers to the tragedy that took the lives of her aunt and two great uncles, as well as reporter Brad Edwards’ efforts to track down Lewis, finally encountering him face to face at Lewis’ apartment building, with Lewis refusing to engage.

The Netflix series has higher production values and benefits from having that sit-down interview with Lewis. It does a solid job of chronicling the case through the requisite use of recollections from investigators, reporters, and friends of the deceased, combined with instructive graphics mixed with archival news footage—but if you know the particulars of the case, there are no groundbreaking revelations to be found in either series. Many of the law enforcement personnel who were part of the investigation remain convinced that Lewis was the killer; others maintain that Lewis, who served 12 years in prison for sending an extortion note to Johnson & Johnson, couldn’t possibly have committed the crimes.

In addition to the two documentary series about this case, Chicago Tribune investigative reporters Christy Gutowski and Stacy St. Clair hosted a solidly sourced podcast titled “Unsealed: The Tylenol Murders” in 2022—but we’ve never seen a big, splashy, theatrically released drama or streaming series, ala “Zodiac,” “Summer of Sam,” “Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story,” “Mindhunter,” “American Crime Story: The Assassination of Giana Versace,”, the Netflix film “Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile” about Ted Bundy, et al. Given the dramatic richness of the material (said with no disrespect to the victims and their families), that comes as something of a surprise.

There are so many twists and turns, so many stunning coincidences, so many indelible images, so many moments of heartbreaking fate in this story. Stanley and Teresa Janus joining a family gathering to mourn the death of Stanley’s brother Adam, only for Stanley and Teresa to take Tylenol at the house and succumb as well. Chicago Mayor Jane Byrne called a live television press conference at midnight to announce a citywide ban on the sale of all Tylenol products. Police cars going up and down the street to give warnings, and police officers knocking on doors. Warnings broadcast via a news crawl during football games. (Getting information to the masses was such a different thing in the pre-Internet, pre-Social Media days.) James Lewis penning a Zodiac-esque extortion letter to Johnson & Johnson, writing, “Gentlemen: As you can see, it is easy to place cyanide, both potassium and sodium, into capsules sitting on store shelves.” The bizarre and tragic episode involving Roger Arnold, who became a suspect (but was exonerated), blamed a local bar owner for turning him over to the police, went to the bar intending to kill the owner, but mistakenly shot and killed a 46-year-old father of six who resembled his intended target. Not to mention the case of the woman in Westchester County, NY, who died from cyanide poisoning after ingesting Tylenol capsules in 1986—some four years after the Chicago-area deaths, and while James Lewis was in prison.

In the final episode of the Netflix series, FBI Special Agent Grey Steed notes, “I think that all of us that were actively involved in the case, believe that James Lewis not only wrote the letter, but planted the cyanide leading to the deaths of seven people,” while former Chicago Police Supt. Richard Brzeczek says, “James Lewis is an a******, but he is not the Tylenol killer.”

After more than four decades, here we are. We might see more true-crime documentaries or podcasts, maybe even a theatrical release or streaming dramatic series someday. But it’s likely the Tylenol murders will never be solved. We’ll never know for certain the identity of the bogeyman who didn’t crawl through an open window or hide under a bed, but terrorized a community through the placement of random boxes of pain on local store shelves.