My few but uproarious interviews with Mel Brooks disproved the adage about never meeting your heroes. He was the Mel a fan would want him to be—always “on,” eager to please and promote (and that’s only the p’s), and a fount of great show-business stories.

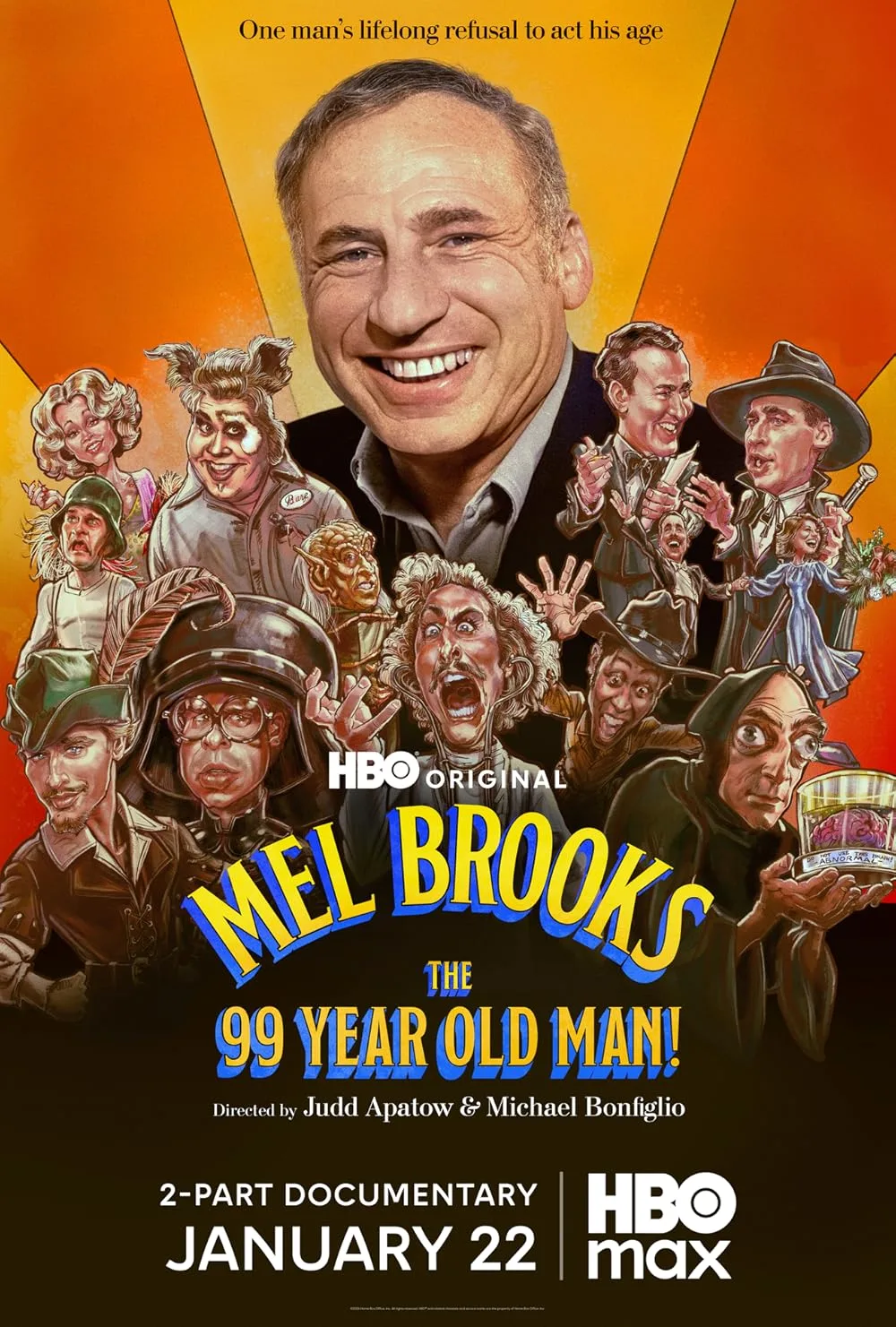

Judd Apatow’s superb two-part documentary “Mel Brooks: The 99-Year-Old Man!” contains definitive versions of several classic Brooks anecdotes, but as with his docs “George Carlin’s American Dream” and “The Zen Diaries of Garry Shandling,” Apatow is most interested in learning who the artist really is.

Apatow, a self-professed “comedy nerd,” had his work cut out for him with Brooks, who confesses to him that in past interviews, he had been, shall we say, “inaccurate,” or used jokes to create a “public persona of Mel Brooks,” which might be summed up as, in his words, “Your favorite Jew.”

“Do you think people know who you really are?” Apatow asks. “No,” Mel replies.

After almost four hours, they will at least have a better sense of him. Apatow etches an indelible portrait that reveals what makes Mel Brooks run. A recurring theme throughout is Brooks’ anything for a laugh ethos and craving for an audience’s approval. In the opening clip, Brooks recreates the telling song that served to introduce himself to Catskills resort audiences when he was just starting out following his service in World War II:

“Here I am, I’m Melvin Brooks

I’ve come to stop the show.

I’m just a ham who’s minus looks

But in your heart I’ll grow…

Out of my mind,

Won’t you be kind?

And please love Melvin Brooks.”

Notes Larry Gelbart, with Brooks one of the legendary dream team of writers on “Your Show of Shows,” “[When he was born] Mel thought that when he got slapped in the ass that it was applause and he has not stopped performing since.” Brooks himself tells Apatow that, as a teenager, he became a drummer (taught by the Brooklynite contemporary Buddy Rich) because it was a way to draw attention to himself.

The archival interviews, film clips, and performance footage are deftly curated (although completists may miss acknowledgement of Ernest Pintoff’s 1963 Oscar-winning short “The Critic” and the short-lived TV series, “When Things Were Rotten”). But what will linger are the more reflective moments from Brooks, his children, friends, and a distinguished group of comedians, screenwriters, and directors who reflect on his legacy of how Brooks used the silliest and most scatological humor to shine a light on the darkest of subjects, such as fascism, racism, and antisemitism. “Comedy helps minimize terrible things,” offers Dave Chappelle, who in his late teens made his feature film debut in Brooks’ “Robin Hood: Men in Tights.”

Part one—premiering Jan. 22 on HBO, with part two following the next night—is more conventionally entertaining as it traces Brooks’ inauspicious origin story, a quintessentially American rags-to-EGOT saga. Raised during the Depression, Brooks lost his father to tuberculosis when he was only two. He and his three brothers were raised by their good-natured, yet tough mother. She “filled me with music and raised our spirits,” Brooks recalls, but he feared his future was to toil on Seventh Avenue—the garment district.

The movies, he said, were “a great escape.” His north star clowns were Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, the Marx Brothers, and the now-obscure Ritz Brothers. Seeing the Broadway musical “Anything Goes” starring Ethel Merman was a transformative experience that further fueled his desire for a career in entertainment.

Part one deals with early setbacks (including writing for Jerry Lewis, the poor initial response to “The Producers,” the outright flop of his second film, “The Twelve Chairs”), and his first triumphs, from “Your Show of Shows” and “The 2,000 Year-Old Man” comedy routine co-created with Carl Reiner, to TV’s Emmy-winning series “Get Smart” and “Blazing Saddles.”

There are more career benchmarks in Part two—“Young Frankenstein,” the establishment of BrooksFilms, which gave early career boosts to David Lynch and David Cronenberg, “The Producers’” record-breaking success on Broadway—but here Apatow delves further into the defining relationships that shaped Brooks’ life, his friendship with Carl Reiner, and his marriage to Bancroft.

Seeing the late Rob Reiner talk about his father and Mel’s dynamic is lump-in-the-throat stuff. Though Carl was younger than Brooks, he was embraced as something of a father figure, Rob says.

Jerry Seinfeld observes of the improvisational back-and-forth that shaped “The 2,000-Year-Old Man,” “A third universe is created just because they’re together and they’re so happy to be together.”

That the not-conventionally handsome Catskills tummler could woo and win the stunning Bancroft, “opened the door for all of us,” Adam Sandler jokes, and pointing at Apatow, husband of actress Leslie Mann, adds, “especially you.”

Bancroft’s and Reiner’s deaths devastated Brooks. Nathan Lane shares that Brooks told him, “If you see me, don’t cry and don’t tell me how bad you feel because I have enough fuckin’ tears of my own.” Rob Reiner says that after his father died, Brooks came to his house every night for months because he wanted to remain close to Carl somehow.

By the end of “The 99-Year-Old Man!”, Brooks is no longer deflecting with jokes. When Apatow asks how he deals with the monumental losses in his life, Brooks responds, “There is no answer to that.”

Recent years have seen something of a Mel-aissance, with the limited series “History of the World—Part Two” and the announcement of a sequel to “Spaceballs.” Rob Reiner recalls that when he was a child, he would get excited about an impending visit from Mel Brooks to the house. “Are you the man?” he would ask Brooks.

As “The 99-Year-Old Man!” makes clear, Brooks is still the man—still willing to do anything for a laugh and still wanting us to love Melvin Brooks.

By the way, if you have not seen “The Twelve Chairs,” by all means seek it out. Roger Ebert gave it four stars and called it “more fully realized” than “The Producers.”