Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne, the Belgian brothers who work together as co-writers and co-directors, began their careers with documentaries. As they have moved to narrative features (all set in their home in Liège province of French-speaking Belgium), they have maintained a modest, intimate, deeply compassionate, and very personal documentary tone: Based on extensive research, filmed with handheld cameras in real locations, and with very minimal music.

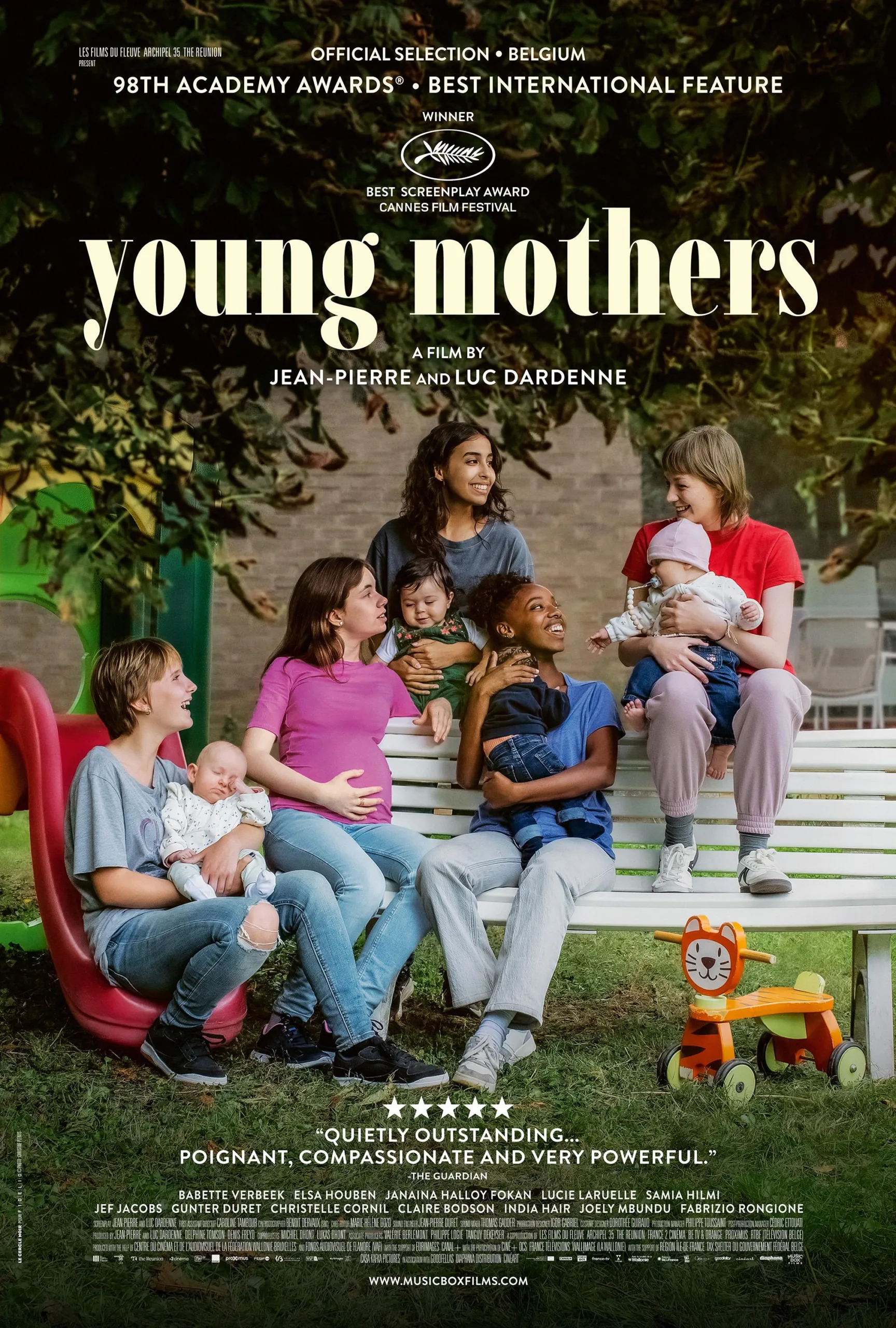

The film is “Young Mothers.” These mothers are very, very young, really still just girls, living in a shelter for pregnant teenagers and then staying with their babies as they transition into jobs and apartments. The four we spend time with are as young as 15, coming from abuse, poverty, and instability, as they try to prepare for the monumental upheavals that come with taking responsibility for a baby. They are so young, and their lives are already so unstable that they barely know how to take care of themselves. While the staff is very much in the background and we barely learn their names, we see they are endlessly patient and kind, yet ready to be firm about boundaries and consequences when needed. The atmosphere they create, expecting each of the girls to support the others, is as important as the lessons in bathing, feeding the babies, and looking for a job.

The young actresses, their faces often filmed in close-up, are so open, vulnerable, and heartfelt that it’s easy to believe this is another documentary. And for the youngest performers, it is. Babies do not take direction, so the actors had to respond in character to whatever they did. The absence of a soundtrack adds to the documentary tone, but that does not mean music is unimportant. One of the young mothers asks a prospective adoptive couple just one question: Do either of them play an instrument, and will they teach her baby music? And then, at the end of the film, two diegetic pieces, one with lyrics by Apollinaire, one with music by Mozart, gently leave us with a sense of optimism and beauty.

We first see Jessica (Babette Verbeek) at a bus stop. It opens on a close-up of her face, so young she barely seems old enough to babysit. But then we see she is pregnant and very agitated. She is looking for someone she does not know, but the one she is waiting for does not show up. Jessica is there to meet her biological mother for the first time. Being pregnant has made her determined to find out why her own mother gave her up. She is so concerned about meeting her mother that she can hardly think about the baby coming in a few weeks.

Perla (Lucie Laruelle, a stand-out even among this excellent cast) is excited and happy because her baby’s father, Robin (Günter Duret) is about to get out of juvie, and she is sure they will move in together in the apartment she has arranged with the help of the shelter, and then they will be a happy family. But we can see her desperation to make it work is not letting her see that he is selfish and manipulative. It is clear to us that this is not going to work out, and when it becomes clear to her, she is devastated and furious, and that leads to a bad decision.

Julie (Elsa Houben) is the only one with a stable and devoted partner, her baby’s father, Dylan (Jef Jacobs), and they’ve been approved for an apartment they love. But both are former drug addicts, and Julie is having difficulty staying clean. Ariane (Janaïna Halloy Fokan) is under enormous pressure from her unreliable mother (Christelle Cornil), who insists that her daughter and granddaughter move in with her, perhaps to make up for her failure to care for Ariane, perhaps just more denial of her own selfishness and instability.

A young mother gives her child to an adoptive couple, writing a letter for her daughter to open when she is 18 (“three years older than I am now”). Another briefly abandons her baby and is only allowed limited contact until she can prove she is responsible. The film is deeply sympathetic to the impossibly difficult choices these girls face and respectful of their efforts to do better for their babies than their parents did for them.

The Dardennes, frequent recipients of awards at the Cannes Film Festival, won the Best Screenplay Prize for this, as well as the Ecumenical Jury award, given to “honor works of artistic quality which are witnesses to the power of film to reveal the mysterious depths of human beings through what concerns them, their hurts and failings as well as their hopes.” That describes this film perfectly.