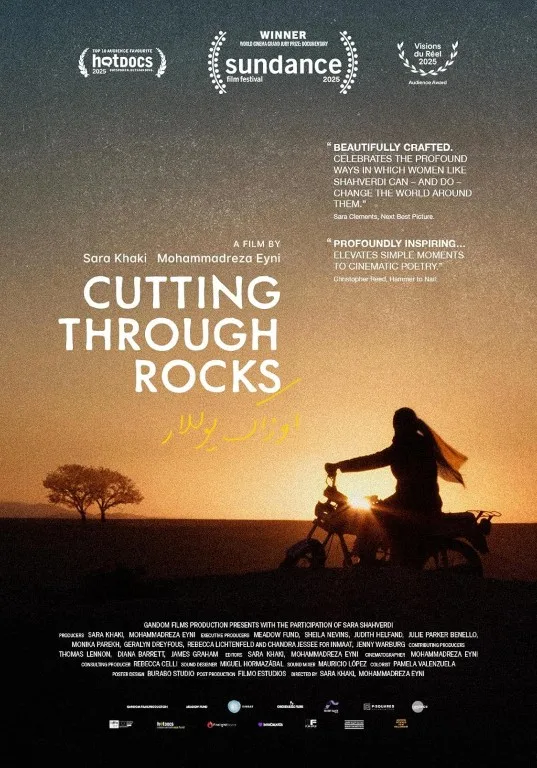

Co-directors Sara Khaki and Mohammadreza Eyni begin “Cutting Through Rocks” by watching their subject fumble with a heavy metal door. Sara Shahverdi can’t get it to fit into the hinges. But why? It was there before. Why must she now take a circular saw to the stone foundation to nestle it back into place?

We don’t get answers to this seemingly innocuous question, but the inquiry lends itself to a metaphor on the state of women in Iran post-revolution. What had once been in place–encouragement of education, heightened marrying age, the ability to divorce and work in public sectors, etc.–is no longer feasible without enacting force on the foundation: the patriarchal social governance of Iran.

Sara Shahverdi, 43, is the face of resistance for her rural Iranian village. The first (and only) woman to be elected to her village’s council, her ambition, and the consequential opposition, is the subject of Khaki and Eyni’s film. Shahverdi is the daughter of a father who, fatigued with having female children, raised her with access to the “masculine.” He taught her construction, how to ride motorcycles, took her into spaces reserved for men, and provided her with a level of self-efficacy and freedom traditionally exclusive to sons. As an adult, Shahverdi is divorced. She lives alone. She wears pants and collared shirts. She is a walking taboo but wears her defiance proudly.

She seeks not simply to be the trailblazer that she is, but a mentor and activist on her local scale. Upon her election, she promised to do the work to facilitate the installation of gas lines for the homes in the village. However, she only does so if the husbands sign partial ownership of their homes over to their wives. In this mission, the number of homes co-owned by women more than doubles. Yet she doesn’t make these accomplishments without the steadfast opposition of local men, including her own brother, a former council member, who not only tries to stomp over her projects, but also attempts to swindle her and all her sisters out of inheritances.

Formerly a midwife, Shahverdi is proud to have delivered over 400 babies. She has no children of her own, but certainly plays a part in trying to raise young girls into independent women. She visits their schools, encouraging them to pursue education rather than marriage. She suggests waiting until they’re 24, and the girls giggle and counter with 30. The tragedy is that even as the girls sign their oath, the choice is not theirs to make. Child wifehood is rife in Shahverdi’s village, and through a teen girl, Fereshteh, who becomes close with her, we see just how many immoveable forces must be conquered on the path to agency.

Feresteh is 16, married for four years to a man 23 years her elder, and in a chilling scene, she pleads to a judge for the right to divorce before she becomes pregnant, and therefore, trapped. The responses include “it is what it is” and “adjust yourself and try to accept him instead of destroying [the marriage].” This peek into the judicial system, intrinsically woven with misogyny, is only a toe-dip into the absurdity we encounter later on, as a court-ordered investigation into Shahverdi’s gender (on account of her unwillingness to obey norms) comes into play.

But against the brutish patriarchy, Shahverdi does not lose faith nor steam. She pick-and-rolls. She teaches the girls in the village how to ride motorcycles, giving them a taste of high-speed freedom that proved instrumental in her own upbringing. She tells them “when you’re ready, hit the gas without fear,” and as the young girls take over, dust kicking up over their wheels, we see the true hope in “Cutting Through Rocks.”

However, the film loses quite a bit of steam in its latter third, dropping focus and shifting between a number of out-of-the-blue elements with clumsy hands. At the same time, so much reflection is put into a sepia photograph of Shahverdi and her father, but not enough time is dedicated to Shahverdi’s history as a young woman. We’re introduced to how her father inspired her unconventionality, but not much else about him as a person. Her missing him is the backbone to the hurt behind the male oppression she faces in the present. One wonders about his relationship to the revolution. Also, what was her life like as a young tomboy under his tutelage?

The film sprinkles in a bit of her own wedding footage as a foil to a child bride’s, but this anecdote feels like an afterthought. At just about 88 minutes of runtime, with much of it including arguments with her brother and discussions of a park she plans to build, “Cutting Through Rocks” confuses its priorities. Often, it opts in to showing cycles of opposition and resistance at arm’s length distance, and by the time we see Shahverdi’s tough facade crack, it feels much too late.

The film grants hope for the women of Iran through its thick-skinned subject, putting her resume and grit on display. But with sharper editing and a bit more eagerness for the personal, “Cutting Through Rocks” would supersede general hopefulness for a more intricate touch to the heart.