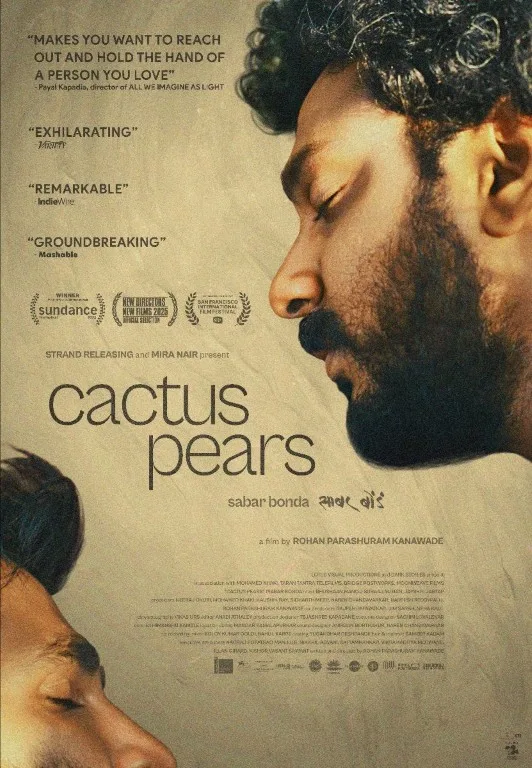

There are few gentler films you’ll find this year than Rohan Kanawade’s “Cactus Pears.” A touching queer romance whose subtle rhythms pull us into its tender embrace.

In following a man grieving the death of his father and his journey back to his small, traditional village, Kanawade offers an affecting culture clash between tradition and modernity, rural and urban, heteronormativity and queerness, with an unhurried deliverance that inspires moments of overwhelming beauty. The Marathi language film gathers instances of devastating sadness and male affection into a search for belonging. Upon premiering at Sundance, “Cactus Pears” won the festival’s Grand Jury Prize Dramatic in the World Cinema Dramatic Competition. With a film whose most seismic truths arise from modest gestures, Kanawade has crafted a work that asks us to consider how love can be born from loss.

The film’s opening shot is one of reflection: Anand (Bhushaan Manoj) wears an exhausted expression in an extreme close-up, as though his entire world has disappeared. The next full shot reveals him to be sitting with his mother, Suman (Jayshri Jagtap), in a hospital waiting room. When Anand leaves the frame to bring in his relatives, Kanawade doesn’t cut to the action happening outside this space. He instead holds on Suman, capturing the wellspring of tears that slowly but mightily pour out. Her husband, Anand’s father, is dead—and Anand doesn’t quite know what to do.

At first, he tries to wiggle out of the customary 10-day mourning period, claiming that he’ll appear for the first two days, leave, and then come back for the tenth. It’s only his mother’s protests that eventually pull him back home from Mumbai. On the way there, he writes and deletes a text message addressed to a man named Chetan, whose profile picture shows him with a family. Once there, in his small village, Anand appears to be in the way: he trails at the back of the frame, standing modestly without any idea what to do with his hands.

From the moment Anand arrives in his village, he is bombarded by tradition. Because he’s unmarried, his relatives believe he shouldn’t light his father’s funeral pyre. They also demand that he not wear his black t-shirt, even if he says it’s really dark grey. There are other rules he must abide by during the 10-day mourning period: No footwear until the tenth day, or going to anyone’s house—if he does, he must sit on the floor. He must also sleep on the floor and limit himself to two homemade meals a day, with no extra helpings, rice, or milk. He can only drink black tea and must not enter temples or trim his hair or beard.

Despite the gravity with which they deliver these rules, it’s obvious there’s some leeway or confusion. If Anand’s hungry in between meals, he can eat fruits. Also, no one’s sure whether he can wash his head. These customs aren’t discredited—Anand ultimately respects these tenants—but Kanawade also isn’t afraid to play up their absurdity for winking laughs.

While Anand can follow these guidelines without much worry, there’s a glaring blemish he can’t hide. He isn’t married. His mother has explained away his bachelorhood by concocting a story that frames Anand as a man so heartbroken by the infidelity of a potential spouse that he now can’t bring himself to marry until he finds the perfect woman.

That story, of course, doesn’t hold a drop of water. Anand is gay.

And what makes his father’s passing particularly hard is that he accepted his son’s homosexuality despite, like Anand’s mother, deciding to keep that truth away from their family. Anand’s extended relatives buy this subterfuge mostly because he lives in Mumbai, and they consider the city strange enough to explain away whatever questions they might have. The only hitch in Anand’s presentation is the allure of his former flame, Bayla (Suraaj Suman). Within a day of Anand’s arrival, the pair begin seeing each other again, sharing furtive glances and motorcycle rides across the vast plains.

Kanawade has a knack for imbuing the smallest action with a sense of care. Consider the moment where Anand and Bayla spend a night sitting together near a square. As Anand smokes, Bayla observes him. Kanawade and his DP Vikas Urs employ their static lens again, allowing us to catch every detail of Suman’s palpable performance: his nervous gulps, his eyes tilting up and down Anand’s lithe frame, his shy posture. At another point, Bayla can’t help but caress Anand’s curly hair—Kanawade opts for an extreme close-up to bask in Bayla’s soft fingers twirling Anand’s fluffed hair. A nighttime dip in a pond offers another opportunity for a full embrace, dissolving away whatever fear Anand might have of being discovered. And of course, the deliverance of de-thorned cactus pears, whose red fleshy heart mirrors this simmering romance, serves as a thoughtful, thematically relevant aphrodisiac.

The filmmaker displays an even softer touch as he builds his characters. Anand’s stern mother is revealed to be softer, kinder, and far more understanding than we might have initially perceived. Bayla, like many of the closeted men in the village, ponders what it might be like to leave. Anand works an exploitative job that demonstrates how the urban brings its own systemic limits. In this sense, Kanawade’s choice of a frame with rounded edges symbolically and aesthetically establishes this world as one featuring elastic people taking circuitous routes toward happiness. And like the titular fruit at the center of “Cactus Pears,” sweetness abounds at the core of its compassionate beauty.