Starting with crane shots soaring over a sun-burnished African plain as lush orchestral and choral music ascends on the soundtrack, “Winnie Mandela” initially promises little more than slick hagiography suitable for the Hallmark Channel. But by the time it ends 100 minutes later, Darrell Roodt’s film has delved into some thorny historical territory, creating a compelling and credible portrait of a controversial woman.

With reports of the 95-year-old Nelson Mandela’s fragile health appearing almost daily on American TV, and the Weinstein Company’s biopic “Mandela: Long Walk to Freedom” slated for release later in the fall, we seem to be in a Mandela moment. If so, Roodt’s account of a woman who went from being idolized as “Mother of the Nation” to scorned as a criminal gang leader deserves a place in the reconsiderations of South Africa’s astonishing transition from apartheid tyranny to multi-ethnic democracy.

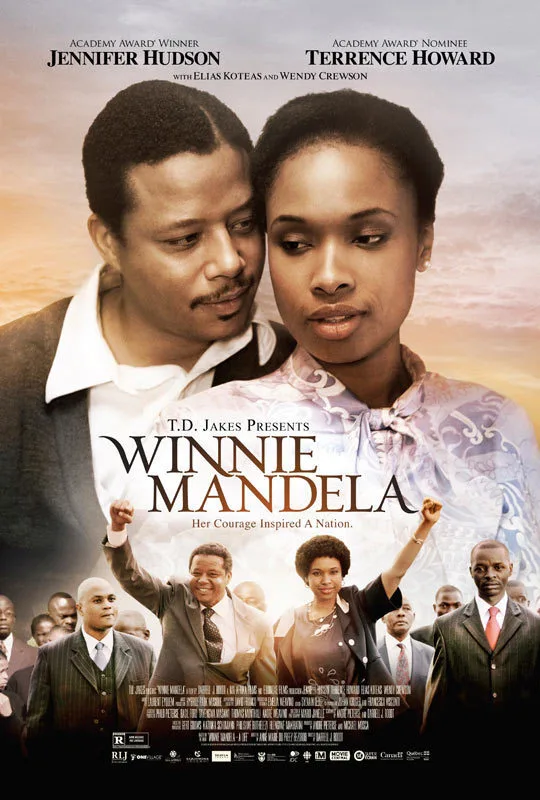

As Roodt tells it, that revolution’s most famous female leader was born to be a scrapper. The sixth daughter of a village teacher aching for a son, she decides to play the male role and becomes adept beating at stick-fighting. There’s nothing masculine, though, about the grown Winnie (Jennifer Hudson), who goes to college in the city and attracts the attention of Mandela (Terrence Howard), a young lawyer already gaining fame and provoking the authorities with his demands for racial equality.

Even before she and Nelson become a serious item, Winnie surprises her friends and colleagues by turning down a chance to study in the U.S. in order to be a social worker in Soweto. Once the two wed, their commitment to their causes (his soon becomes hers) is tested in increasingly severe ways. The two are under seemingly constant surveillance by cops led by one De Vries (Elias Koteas in a commendably restrained performance), a steely nemesis who plays like a composite of what must have been a small army of officials assigned to harass and derail the Mandelas.

Arrested with three other black leaders and tried for treason, Mandela narrowly escapes the death penalty and instead is sentenced to life imprisonment. On the rare occasions when Winnie is allowed to visit him on Robben Island, the authorities do everything they can to keep them from communicating. Increasingly left to her own devices, Winnie also endures her own hellish stint in prison, where she’s kept in solitary for 500 days. When Mandela sees her after the ordeal and asks in horror, “What have they done to you?” she replies stoically, “Made me stronger.”

That may sound like standard biopic bravado, but it leads aptly into the roughest patch of Winnie’s story. Allowed back to Soweto after a period of internal exile, she is thrown into a situation where rival anti-apartheid factions are engendering horrific black-on-black violence, including the grisly practice of “necklacing” (putting a tire around a bound victim and setting it afire). Seemingly as a way of creating a buffer around herself, Winnie becomes the sponsor of the Mandela United Football Club, a kind of township mafia in soccer togs. Nelson, still imprisoned, accurately describes them as “thugs,” and demands to know if Winnie is sleeping with their leader. She doesn’t answer.

Winnie’s plunge from worldwide heroine to de facto pariah is completed when a 13-year-old football club hanger-on named Stompie (Abel Ndele) is killed by other members who suspect him of being an informant. While the film doesn’t examine whether or not Winnie knew of the murder in advance, any more than it shows her in any extra-marital dalliances, it deserves great credit not just for depicting these enormously unflattering episodes, but for doing so in a way that makes one woman’s slide from saint to sinner both believable and, to an extent, understandable.

Mounted with Hollywood-style plushness and polish, this Canadian-backed production exhibits its share of biopic clichés, oversimplifications and hackneyed devices like using newspaper headlines to convey information. Yet its most salient quality is an emotional richness that’s owed largely to two forceful performances at its center. Terrence Howard, a resourceful actor in all circumstances, gives a magnificent account of Mandela, one of those rare heroes who seems entirely human too. And Jennifer Hudson, though her actorly range is not nearly as great as Howard’s, does a fine job conveying Winnie’s peculiar combination of fierce strength and unexpected vulnerability.

Ultimately, Winnie is a woman who seems to embody the paradoxes of her country’s turbulent history. Mandela, deciding that the stain of the Stompie affair makes her an unsuitable First Lady for the new South Africa, divorces her and remarries (which she never does). At the Truth and Reconciliation hearings in the ’90s, she is held “politically and morally accountable for the gross violations of human rights committed by the Mandela United Football Club.” Yet she apologizes to Stompie’s mother and is elected president of the African National Congress’ Women’s League. In the end, hers is a journey as complicated and fascinating as that of South Africa itself.