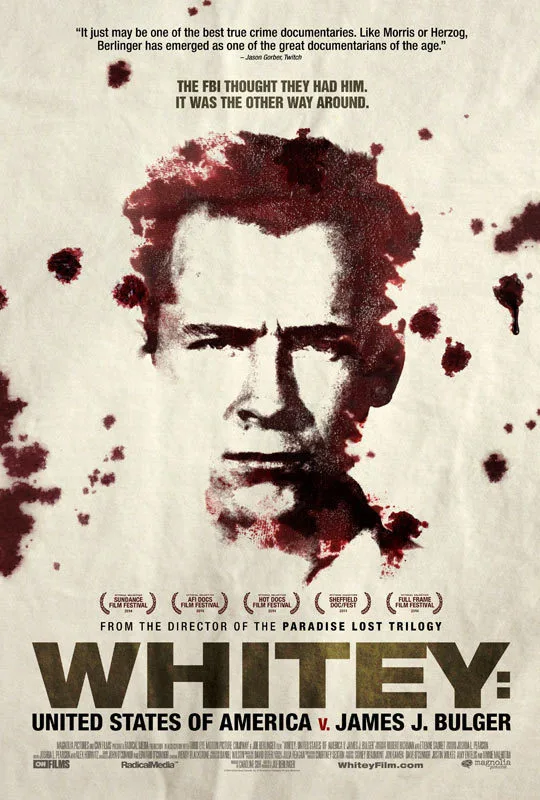

Most films focusing on criminal trials aim at revealing the accused’s guilt or innocence. In Joe Berlinger’s “Whitey: United States of America V. James J. Bulger,” however, there’s no doubt that Boston crime lord James “Whitey” Bulger was a very bad guy with tons of criminal misdeeds including murders to his discredit, and those who followed his 2013 trial will know he was convicted of a number of these and sentenced to spend the rest of his life behind bars. The real question of culpability that provides an element of suspense here, ironically, concerns not the obvious baddies but the ostensible good guys: How much of Whitey’s career was facilitated and furthered by corrupt government figures, especially ones in the FBI and U.S. department of justice?

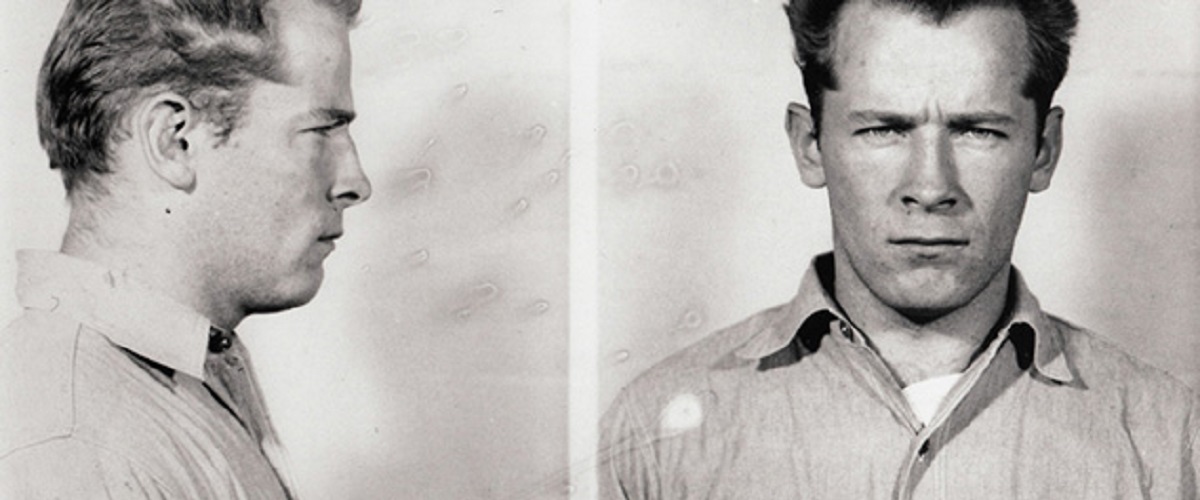

Whitey, after all, ran the Irish mob in Boston for nearly 30 years without a single arrest, even a misdemeanor. (He was apprehended in California in 2011 after fleeing his native state and living for years under false identities.) How did he get away with it? Pretty much everyone concedes some level of official corruption and complicity, but the issue is what he did to get it. In his trial, Whitey admits to bribing (often with lavish cash Christmas “presents”) pretty much every officer of the law he came into contact with. But some maintain that he gave the lawmen something else as well: information.

Was Whitey an informant? Strange that such activity is not criminal and thus is nowhere mentioned in the counts against Bulger, yet it becomes a central issue in the trial, the defense vigorously denying it and the prosecution everywhere asserting and implying it. That, it appears, is because both sides assume that Whitey will be convicted of most of the charges and then locked away forever. The real issue of contention, then, is reputation; or to use the term of choice, “legacy.”

If Whitey ratted out his fellows, he is the lowest of the low, a man without honor anywhere in the universe. If, on the other hand, this is all a smear, then he can still portray himself as a “good bad guy” and hold his head up in the criminal underworld. A similar concern is attached to only one other issue: whether he killed two women (with his bare hands, no less). Good bad guys don’t murder the fairer sex, so Whitey’s defense team takes pains to deflect the charge onto other miscreants.

In centering his film on the trial, Berlinger commendably finds a new angle on Bulger, one of the most storied of modern criminals. (Scorsese’s “The Departed” fictionalized his exploits, and there are reportedly two big movies about him in the works now, one starring Johnny Depp, the other mounted by Ben Affleck and Matt Damon.) But of course, covering the trial is also a prism for looking at Whitey’s whole bloody career and a history of criminals-versus-crimefighters in which the moral lines were often fatally blurred.

Berlinger takes the story all the way back to attorney general Robert F. Kennedy’s exposing the Italian Mafia (“la cosa nostra”), something FBI director J. Edgar Hoover had long denied. The result was that the feds began to focus on Italian organized crime, to the advantage of other kinds. When he came out of prison after a youthful sentence for bank robbery, Whitey offered himself as a middle man between competing criminal factions, which, along with his nerve and ruthlessness, led to his ascendancy as a new kind of crime boss. He also later claimed that protecting federal prosecutor Jeremiah O’Sullivan from revenge by the Italian mobsters, not informing, was what gained him the government’s protection. (The judge didn’t allow this claim into evidence.)

With no cameras allowed in the courtroom, Berlinger has to rely on artists’ renderings and readings of the testimony, with significant statements typed across the screen. Outside the court, he gets interviews with most of the main players. Three prosecutors insisted on being interviewed together (why?) and though this feels a little stilted, their words are forceful. Attorney Jay Carney and others on the Bulger team, in contrast, are loose, nimble and eager to share their evidence against the informant charge. And surely best of all from Berlinger’s standpoint, Carney delivers Whitey himself—at least aurally.

Speaking from prison through his lawyer’s phone, the arch-criminal sounds intelligent, level-headed and passionate to maintain his “good bad guy” reputation. Naturally, his opponents say the image he creates is a total fraud, and that his capacity for lying knows no bounds. Which may be true. With Whitey declining to take the stand (his lawyer says he wasn’t allowed to testify) and his sentence forbidding him to give interviews from prison, this may be the only direct testimony we’ll ever get from the man, and it’s worth hearing to get a sense of his focused, self-exculpatory outlook.

Apart from the defense and prosecution, Berlinger takes his verite camera outside and spends time with the families of Whitey’s victims (he was charged with 19 murders, many very brutal). These are the film’s most moving sections and the filmmaker handles them with both sensitivity and tact. Understandably, many of these ordinary Bostonians (some of whose loved ones just happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time) have harbored a fierce hatred of Whitey and desire for justice to be meted out to him at long last. Yet while most of this comes to pass, many of them remain frustrated because they’d wanted something else too: the government’s role in his misdeeds to be fully aired and documented.

While we get to see many of Whitey’s former cohorts ratting on each other (truthfully or not) to earn leniency, and some of the guilty among the FBI and the department of justice are named, the evidence suggests that only corruption on a large, systemic scale could have sheltered a criminal as massively guilty as Whitey for decades, and the trial doesn’t end up painting a clear picture of this. A masterful documentarian (“Brother’s Keeper,” “Paradise Lost”), Berlinger has been criticized for not making that picture clearer himself, as well as for not favoring the evidence that Whitey was indeed an informant. But surely the great value of this fascinating, expertly crafted film is to leave us with the sense that, Whitey apart, justice has not been done as long as official corruption this wide and deep has not been rooted out and fully understood.