Those who have ventured into the darker corners of addiction know that one of its few consolations, once the fun has worn off, is the camaraderie with fellow practitioners. Substance abuse sets the user apart from the daily lives of ordinary people. No matter how well the addict may seem to be functioning, there is always the secret agenda, the knowledge that the drug of choice is more important than the mundane business at hand, such as friends, family, jobs, play and sex.

Because no one can really understand that urgency as well as another addict, there is a shared humor, desperation and understanding among users. There is even a relief: Lies and evasions are unnecessary among friends who share the same needs. “Trainspotting” knows that truth in its very bones. The movie has been attacked as pro-drug and defended as anti-drug, but actually it is simply pragmatic. It knows that addiction leads to an unmanageable, exhausting, intensely uncomfortable daily routine, and it knows that only two things make it bearable: a supply of the drug of choice, and the understanding of fellow addicts.

Former alcoholics and drug abusers often report that they don’t miss the substances nearly as much as the conditions under which they were used–the camaraderie of the true drinkers’ bar, for example, where the standing joke is that the straight world just doesn’t get it, doesn’t understand that the disease is life and the treatment is another drink. The reason there is a fierce joy in “Trainspotting,” despite the appalling things that happen in it, is that it’s basically about friends in need.

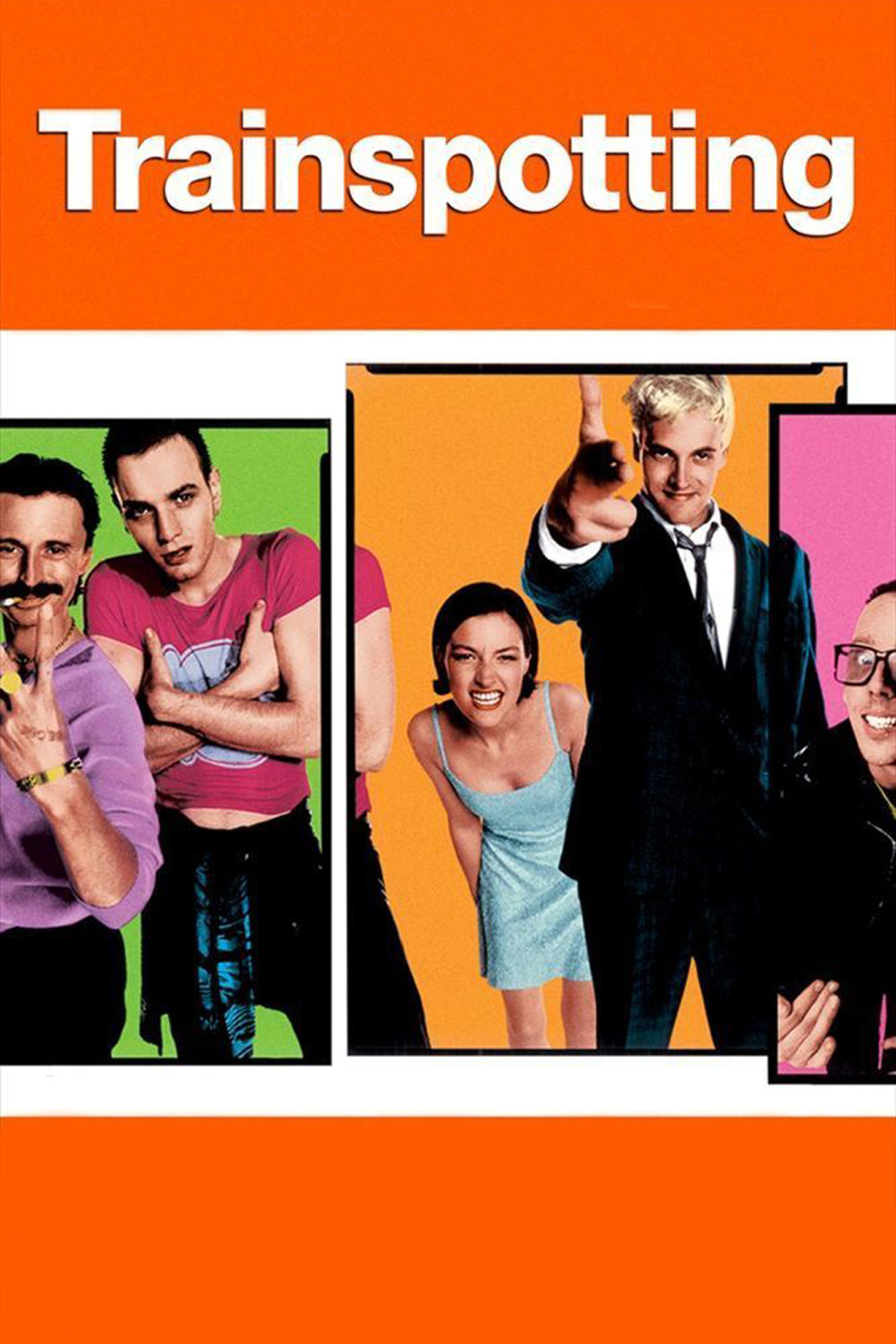

The movie, based on a popular novel by Irvine Welsh, is about a crowd of heroin addicts who run together in Edinburgh. The story is narrated by Renton (Ewan McGregor), who will, and does, dive into “the filthiest toilet in Scotland” in search of mislaid drugs. He introduces us to his friends, including Spud (Ewen Bremner), who confronts a job interview panel with a selection of their worst nightmares; Sick Boy (Jonny Lee Miller), whose theories about Sean Connery do not seem to flow from ever having seen his movies sober; Tommy (Kevin McKidd), who returns to drugs one time too many, and Begbie (Robert Carlyle), who brags about not using drugs but is a psychotic who throws beer mugs at bar patrons. What a lad, that Begbie.

These friends sleep where they can–in bars, in squats, in the beds of girls they meet at dance clubs. They have assorted girlfriends, and there is even a baby in the movie, but they are not settled in any way, and no place is home. Near the beginning of the film, Renton decides to clean up, and nails himself into a room with soup, ice cream, milk of magnesia, Valium, water, a TV set, and buckets for urine, feces, and vomit. Soon the nails have been ripped from the door jambs, but eventually Renton does detox (“I don’t feel the sickness yet but it’s in the mail, that’s for sure”), and he even goes straight for a while, taking a job in London as a rental agent.

But his friends find him, a promising drug deal comes along, and in one of the most disturbing images in the movie, Renton throws away his hard-earned sobriety by testing the drug, and declaring it… wonderful. No doubt about it, drugs do make him feel good. It’s just that they make him feel bad all the rest of the time. “What do drugs make you feel like?” George Carlin asked. “They make you feel like more drugs.” The characters in “Trainspotting” are violent (they attack a tourist on the street) and carelessly amoral (no one, no matter how desperate, should regard a baby the way they seem to). The legends they rehearse about each other are all based on screwing up, causing pain, and taking outrageous steps to find or avoid drugs. One day they try to take a walk in the countryside, but such an ordinary action is far beyond their ability to perform.

Strange, the cult following “Trainspotting” has generated in the UK, as a book, a play and a movie. It uses a colorful vocabulary, it contains a lot of energy, it elevates its miserable heroes to the status of icons (in their own eyes, that is), and it does evoke the Edinburgh drug landscape with a conviction that seems born of close observation. But what else does it do? Does it lead anywhere? Say anything? Not really. That’s the whole point. Drug use is not linear but circular. You never get anywhere unless you keep returning to the starting point. But you make fierce friends along the way. Too bad if they die.